Arbeitslager Trzebinia

Commandant of the camp

SS-Unterscharführer Wilhelm Kowol

Number of SS Guards

Around 70 SS Guards in 1945 from the Wachkompanie Monowitz and former Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe men from the 8th Sentry Company Auschwitz.

Work type

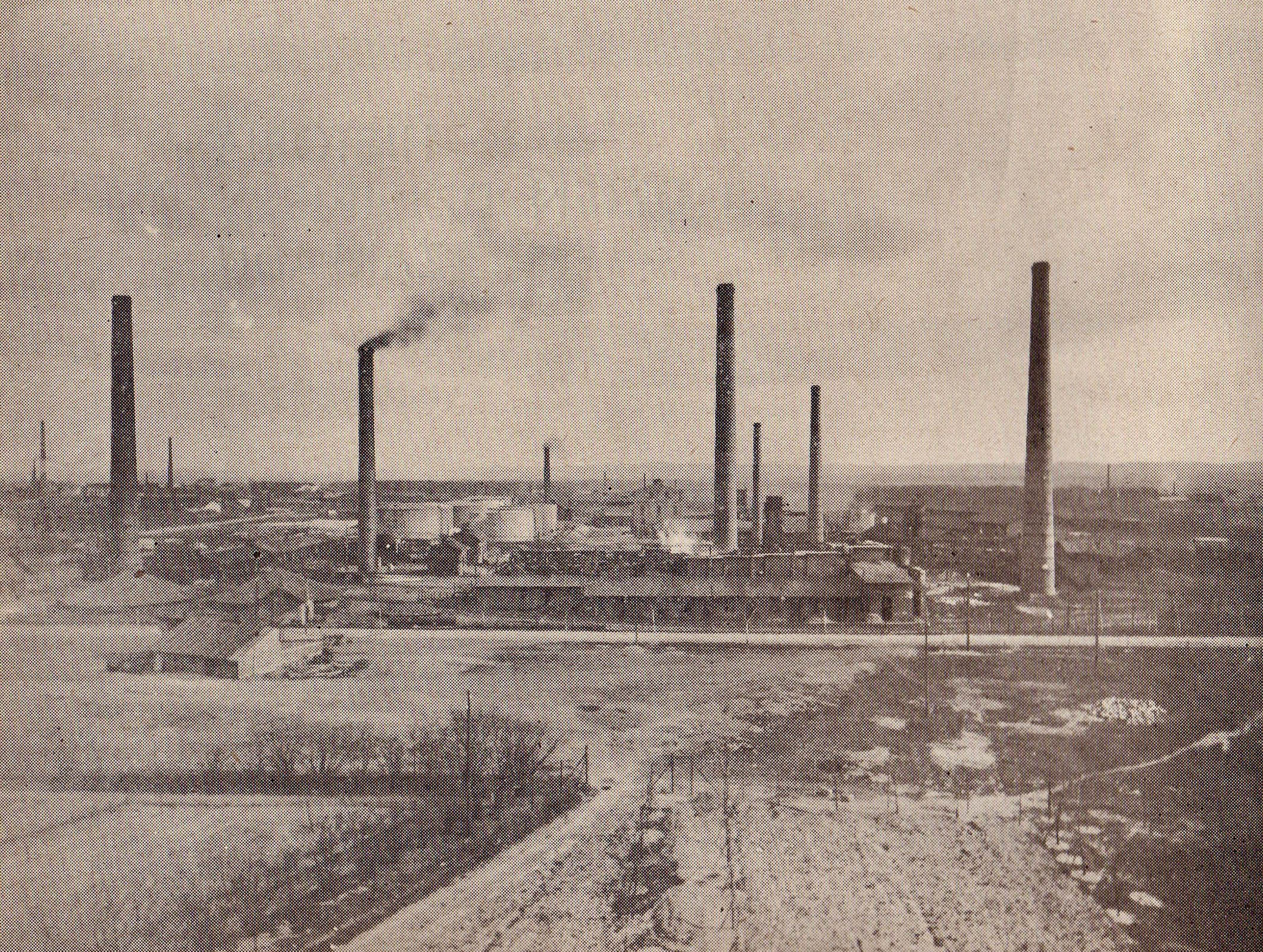

Oil and Chemicals: Expansion of the oil refinery.

Employer

Erdöl Raffinerie GmbH part of Kontinentalen Öl AG Berlin

Sub camp buildings

Originally built for Belgian civilian workers and then a British POW camp. The buildings were then taken over by the Auschwitz sub camp.

Number of prisoners

Between 600-800 male prisoners. 17 January 1945 641 prisoners.

Nationality of prisoners

Mainly Hungarian and Polish Jews.

Period of camp existence

August 1944 – January 1945

Dissolution / Evacuation of the sub camp

On 17 or 18 January 1945 the prisoners were evacuated to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Dates of site visits by Tiergartenstrasse4 Association

June 2006, March 2007 and November 2007.

Memorialisation

On ul Kruczkowskiego in 1970 a monument to the victims of Nazism was unveiled. For reasons unknown, the monument does not contain specific information about the victims of the Auschwitz sub camp.

Explore more

The History

The history of the companies and the places prisoners worked, the sub camps, the SS guards and memorialisation of the sites.

The History of the Trzebinia Refinery

The founder of the refinery in Trzebinia was Count Andrzej Potocki – owner of numerous land estates and industrial plants. On May 6, 1895, he applied for permission to build a refinery from the Governorship in Lemberg (Lviv). One month later, Potocki received the consent issued on behalf of the Emperor Franz Josef by the governor of Galicia, Count Kazimierz Badeni. The new refinery was located near the railway line linking Vienna via Trzebinia and Krakow with Lviv. [1] The refinery was erected between railway tracks from the south and west as well as along private roads from Trzebionka to Trzebinia. [2]

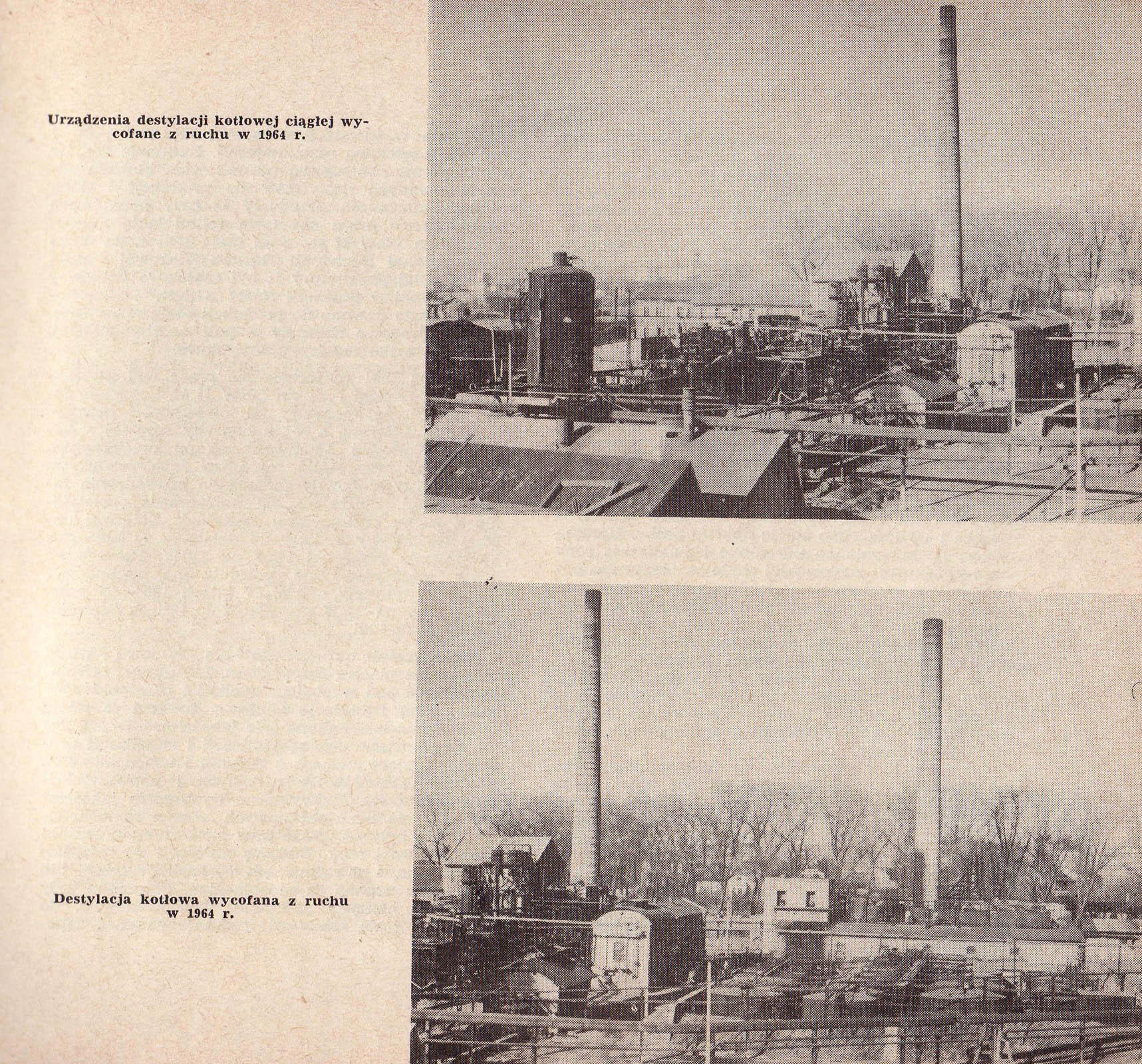

By 1896, the distillation boilers were operational, and were processing crude oil. These distillation boilers processed 400 tons of oil per month. Ludwig Schulz became the first director of the refinery. The main products were various types of oil kerosene – “imperial”, “saloon”, “economic”, “export”. [3]

In 1898, Potocki sold the refinery to the Trzebińska Spółka Akcyjna S.A. During this period, about 250 workers worked in the refinery, from the nearby towns of Trzebionki, Wodna and Luszowice. [4]

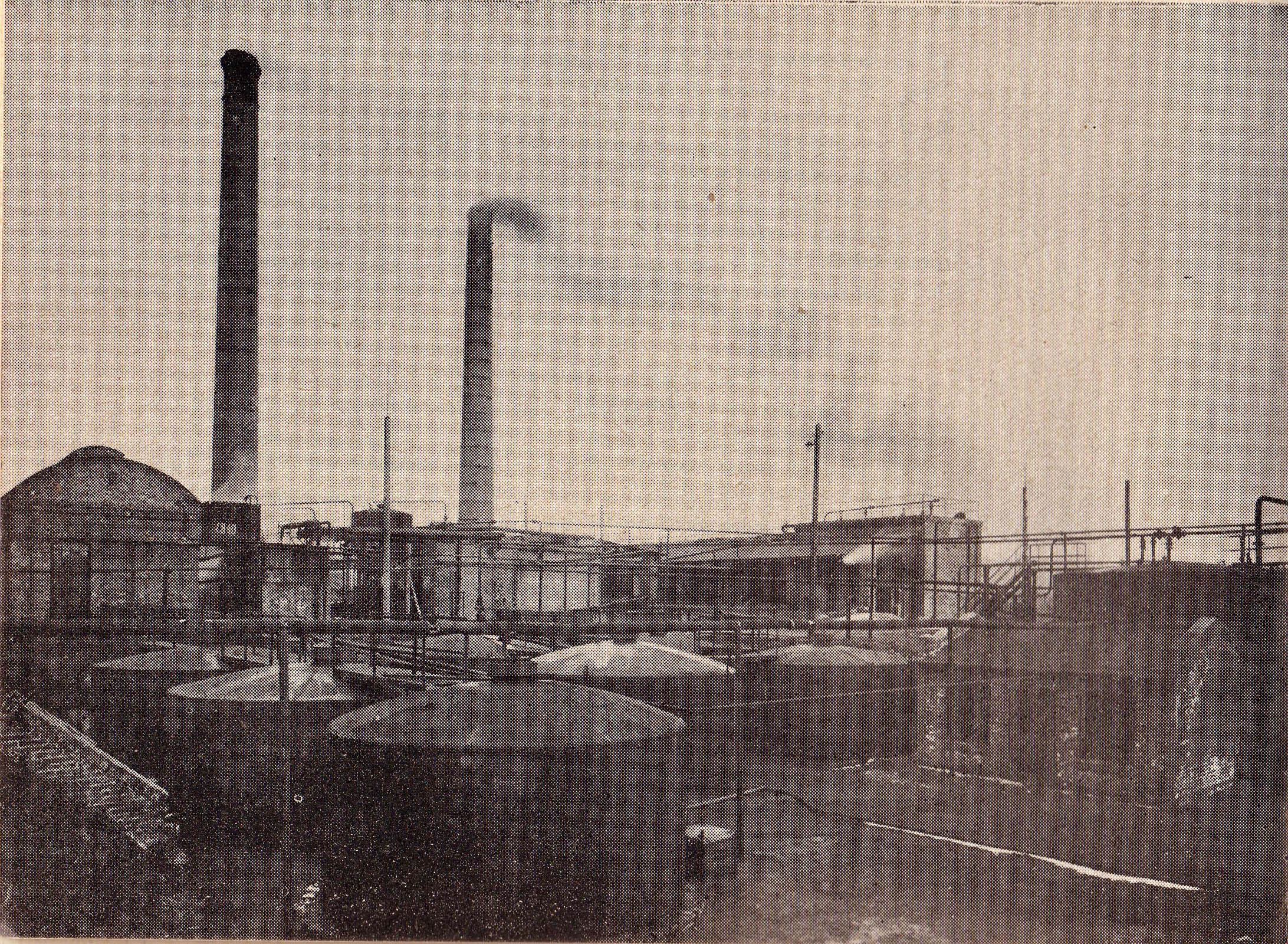

The rapid development of the refinery began in 1903, when it was acquired by the Austrian joint stock company Mineralöl A.G. based in Vienna. Continuous boiler distillation equipment was installed, which was able to process 5,000 tons of oil per month, while in the years 1905-1913, a paraffin plant was built with an annual processing capacity of 12,000 tons. Also built were a coke distillery plant (so-called “kraki”), asphalt oxidation unit, gasoline rectification, equipped with one distillation apparatus without a column, two Heckman system rectification apparatuses with columns and one rectifying apparatus with a column and dephlegmators. Several other buildings, such as a pump station and a laboratory were added. A tank cleaning device was installed. In addition, three DC power generators were installed in the refinery, which allowed it to produce its own power. [5]

In the years 1914-1918, more tanks were built, which allowed the processing of approximately 60,000 tons of oil per year. Around 300 employees were employed during this period.

After Polish independence in 1918, the refinery remained under the supervision of the State Oil Office. Immediately after the end of World War I, the refinery was further developed. According to the protocol of the commission receiving the notices of completed works, by June 21, 1921, it had been possible to build a locomotive station, four new distillery boilers, new filter presses in the paraffin plant, a new boiler room, an electric railway and an 80 m factory chimney. [6]

In 1926-1928 there was a drop in oil production in Poland and the plant underwent little further development. It managed to produce 77,125 tons of gasoline, oil, kerosene, paraffin and asphalt exported to Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Germany, Great Britain and Italy. In the years, before the outbreak of World War Two, 350 people were employed in the refinery, including 25 white-collar workers, 10 engineering and technical workers, and 15 administrators. [7]

At the beginning of the German occupation, the refinery in Trzebinia was sequestered by Beskiden – Erdölverarbeitungs – gesellschaft mbH; Mineralöl Rafinerie Trzebinia O / S Komissarische Verwaltung in Berlin. During the period of operation of Arbeitslager Trzebinia, the plant was controlled by Erdöl Raffinerie GmbH part of Kontinentalen Öl AG Berlin

Shortly after the liberation of this area of Poland in 1945 an inspection revealed the Trzebinia refinery to be one of the most severely damaged plants in Poland. [8] As a result of Allied air raids in August 1944, a significant part of the old refinery, a combined heat and power plant, tanks, workshops and two residential buildings were destroyed. The pipe and tower distillation systems erected by the Auschwitz prisoners had survived, but could not be restarted immediately as the control and measurement apparatus had been disassembled and removed.

[1] Rafineria “Trzebinia”, opracowanie zbiorowe, Krakow 1995, published without pagination.

[2] Trzebionka – wieś, którą w 1961 r. attached to the city of Trzebinia. Currently one of the suburbs of Trzebinia.

[3] Trzebinia. Zarys dziejów miasta i regionu, Edit. Feliks Kiryk, Kraków 1994, p. 223.

[4] Trzebinia. Zarys dziejów miasta i regionu, Edit. Feliks Kiryk, Kraków 1994, p. 223.

[5] Rafineria “Trzebinia” 1895-1970, Krakow 1971, published without pagination.

[6] Trzebinia. Zarys dziejów…, op. cit., p. 361.

[7] Trzebinia. Zarys dziejów…, op. cit., p. 362.

[8] The city was liberated as part of the Soviet offensive on the Vistula-Oder on January 23.

The Post War History of the Trzebinia Refinery

The first meeting of the new Trzebinia Refinery management took place on January 25, 1945, during which the Workers‘ Council was elected. The chairman was Jan Koryczan. They managed to secure the area and remaining property and clear up the most severe damage. The Zjednoczenie Przemysłu Naftowego w Krakowie wanted to rebuild the refinery. It was proposed to establish on the site the Centrala Produktów Naftowych. Meanwhile, they had managed already in May 1945 to get the boiler room, part of the distillation equipment and a pumping station working, which allowed production to restart, processing about 900 tons of oil left by the Germans.[1] Soon afterwards the decision was made to fully rebuild and relaunch the refinery. In 1947 as a result of the nationalisation carried out by the Ministry of Industry and Commerce the refinery became part of the Zjednoczenia Rafinerii Nafty w Warszawie. Continuous production was based on supplies of Persian oil. Simultaneously repairs allowed the launch of continuous boiler distillation, refining of oils and paraffin.

After the construction of a new tube and tower distillery in 1949-1951, the plant became the independent state-owned enterprise Rafineria Nafty Trzebinia. Austrian oil, Romanian mazut and paraffin oil from the Soviet Union were processed there, from which fuels, low-friction diesel, transformer, motor oils, white oils, road and industrial bitumens were produced. [2]

On January 1, 1976, the Trzebinia refinery ceased to be an independent enterprise. With the decision of the Zjednoczenie Petrochemia to reorganise the industry, the Śląskie zakłady Rafineryjne im. Ludwika Waryńskiego was established and took over the refineries in Czechowice and Trzebinia. This state entity lasted until January 1, 1976, when it was decided to separate the plants into independent entities. [3]

As a result of the economic crisis of the 1980s oil processing and commodity production decreased. At the beginning of the 1990s, nearly 800 people were employed, and the product range comprised nearly 80 products. In 1995, the refinery was transformed into the wholly state owned company Skarbu Państwa – Rafineria Trzebinia SA.[4]

[1] Trzebinia. Zarys dziejów miasta i regionu, Edit. Feliks Kiryk, Kraków 1994, p. 565.

[2] Trzebinia. Zarys dziejów…, op. cit.,, p. 566.

[3] Trzebinia. Zarys dziejów…, op. cit.,, p. 566.

[4] Rafineria „Trzebinia”, opracowanie zbiorowe, Krakow 1995, published without pagination.

The History of the Sub Camp Arbeitslager Trzebinia

One of the most important sub camps of Auschwitz, for Upper Silesian industry, was established in Trzebinia. This city, located within the Chrzanów powiat, and the capital of the urban-rural commune, was bombed by the German air force on September 1, 1939. The resistance of the Polish army was quickly broken and on September 5 the Germans carried out the first executions in the area, both among the Jewish population, which at that time constituted a considerable percentage of the inhabitants as well as amongst the Non-Jewish Poles. On October 9, 1939, Trzebinia was incorporated into the Third Reich, and the border with the General Government was drawn at the village of Dulowa. During the war, two prisoner of war camps, three labour camps and a sub camp subordinate to the commandant of Auschwitz were located in Trzebinia. [1] As a result of the extermination policies of the Nazis, about 1/3 of the total population of the town lost their lives.

The sub camp Arbeitslager Trzebinia at the oil refinery [2] in Trzebinia was founded in August 1944 on the initiative of Erdöl Raffinerie G.m.b.H. [3] The camp was located not in Trzebinia itself, but in the village of Trzebionka neighbouring the city of Trzebinia from the north-west. At the refinery in 1942 barracks were built for Belgian workers. Michał Stefański a resident of Trzebionka remembered the Belgians, “Toward the end of 1942, groups of workers from Belgium started arriving in the camp. Most of them were qualified workers – locksmiths and boilermakers. Housed in the barracks, the Belgians were put to work assembling tanks in the Trzebinia oil refinery. At that time these buildings weren’t surrounded with barbed wire, and the Belgians enjoyed relative freedom of movement. During our conversations, they often complained about being hungry. Left unguarded in the camp, they could have contact with the local population. Their difficult work lasted from 10 to 12 hours a day.”[4]

At the end of November 1942 the Belgian workers were moved to private accommodation in Chrzanów and British prisoners of war from the camp in Łambinowice [5] replaced them. A resident of Trzebionka – Władysław Mendela witnessed these events: “(…) I remember that in the late summer of 1943, the construction of the camp [6] was begun in the area near the refinery. Civilian workers worked at the construction site. There were barracks made of corrugated metal, and the area was fenced in with barbed wire (…). A few hundred prisoners of war were brought to the camp. They worked at the refinery. They were young and healthy men. The guards looked quite grotesque in comparison to them – old and decrepit. The English were well fed. Often, they sold us chocolate or other items – probably from their Red Cross parcels. I heard that the camp authorities often had problems with particular groups of these prisoners who refused to go to work. The Germans treated them better than those working in the refinery – Poles.” [7]

A local resident Michał Stefański got to know the British prisoners of war well and helped one of them to escape. “Working in the factory, I had the opportunity to get in contact with, and to talk to the English prisoners of war. From the conversations we held I know that the food rations in the camp weren’t good. They had coffee for breakfast and supper, soup and potatoes or kasha for dinner. They were also given some bread (I am unable to specify how much) and, sometimes, a piece of margarine, marmalade and sausage. They told me that the food they were given was so lousy and smelled so bad that it wasn’t fit for consumption. For this reason they often threw it away. They ate what they received from their families and from the Red Cross. The packages they were sent contained dry foodstuffs, which they traded with the civilian population for bread, fat, and dairy products. They slept on three-story bunks. Each of them was allotted a separate bed. The Germans checked their number during the roll-calls which were held three times a day: in the morning, in the afternoon, and in the evening.

They were very friendly towards the local population – an attitude which they showed at every turn in their smiles and gestures…. As they exchanged food with the locals, they often tried to help them. In saying the “civilian population”, I refer only to the Poles. Immediately upon the arrival of the English soldiers in the camp in Trzebionka, the locals tried to get in touch with them. Living in the close vicinity of the camp, I would go out to see how the Germans treated the English prisoners.

One day, one of the English prisoners of war began to communicate with me in sign language. He even threw me a bar of chocolate. I often talked to him using sign language. At the beginning of January 1944, he tried to communicate using sign language with my twenty year old daughter Maria. From the gestures he made, she understood that he wanted to see her at our home at 19.00 hrs. We didn’t know if it was possible, and we were wondering how he was going to manage it being so closely guarded by the SS men. However, on that day we were waiting for him. At 19.00 hrs he turned up at our place alone. Having introduced himself to my family in German, he spoke to me in that language. At that time my daughter didn’t speak German and, consequently she couldn’t communicate with him. From our conversation I learned that his name was Alexander Todd Wood and that he was Catholic. English by birth, he was the son of Robert and Elisabeth, born on 13 November 1916 in Greenock in Scotland. He told me that he had bribed the German who was keeping guard at the gate and was thus allowed to pay us a visit. A twenty-year old man, the SS man took to Todd. Thanks to the relationship Todd established with the German, he could when it was dark and when the German was on his guard duty slip out of the camp and visit us. Leaving the camp required Todd to take painstaking precautionary measures. He put socks on his shoes in order to avoid leaving shoe prints on the snow. The German always escorted him on side paths to our house. Until 23 January 1944, he visited us almost every other day.

We discussed various topics. He described life in England and talked about the war and the Germans to whom he was hostile. He harboured warm feelings for the Poles. At one point he began to complain about his captivity and declared he had to escape from the camp. Sometime after the conversation – and at the time the German whom he would bribe was on leave and was absent from the camp – Todd arrived at our place. He had previously asked me in a letter he had thrown over the barbed wire to prepare some civilian clothes for him. It was on 23 January 1944. Upon his arrival, along with another English prisoner of war, he said that he and his friend had just escaped from the camp and he asked for civilian clothes which we gave them.

Todd told us how they had escaped. Because it was impossible for too many prisoners to escape at one time, it had been agreed that their fellow prisoners would divert the SS guards attention from one section of the barbed wire. When the latter engaged the SS men in conversation, Todd and his companion cut the wire with cutters and escaped. Afraid that they might be captured at my home – my family and I ran the risk of being executed for hiding them – I told my wife to go with them to Krakow. After a three day stay in Krakow they both returned to Trzebionka. Todd stayed with us and his companion with our neighbour named Struzik. Because the Germans launched an extensive search for the fugitives we thought that our homes would be searched too and that is why we sent both of them to Frydrychowice, to our acquaintance, Stanisław Michalak. After one week Todd returned while, as I heard, his companion joined one of the partisan groups. We put down Todd’s return to the fact that he was very fond of our daughter. Later, he even declared that he wanted to marry her. Todd hid with us until 1 June 1945. As an English soldier, he was under an obligation to report back for duty. Before he left, he wanted to marry my daughter, but the church authorities refused to perform the wedding ceremony because he was a foreigner.

I think that the reason we were able to hide Todd was that the Germans assumed it was highly unlikely for someone who lived so close to the camp, just fifteen meters away, to risk severe punishment and offer shelter to the fugitive. We could also rely on the help of the SS man whom Todd had bribed and who informed us of impending searches and of any other danger we might be in. As Todd was with us, we took painstaking measures of precaution. The door and windows were kept shut and we told Todd to hide in the basement every time someone came to us. Todd paid no attention to the danger to which he was exposed and would walk through the fields and streets with my daughter. My family and I risked a lot, because the English prisoners of war knew that we were hiding Todd and those who decided to escape, which happened a couple of times, always passed through our house, taking advantage of our assistance. The English prisoners of war weren’t subjected to any severe harassment. This is at least what I learned from those whom I came into contact with. At the end of July or at the beginning of August, the English were transferred from Trzebionka to another camp.” [8]

The British prisoners of war were to be employed in the refinery until the end of 1944. However, already in June 1944 the refinery management began efforts to source Auschwitz prisoners to replace the British prisoners of war. On June 20, 1944, an official letter was sent via Auschwitz III-Monowitz to the employment section of the Main Office of Economy and Administration of the SS, in which 1,000 prisoners were requested for the refinery. These planned staffing levels were never achieved. The management of the refinery also specified exactly which skills the prisoners should have and their number: 150 machinists, 300 machine assistants, 5 blacksmiths, 8 welders, 40 bricklayers, 60 concreters, 10 carpenters, 20 steel workers, 387 construction workers and 20 electricians. [9]

The first group of prisoners from Auschwitz arrived in Trzebinia at the beginning of August 1944. They were transported by truck from Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Stanisław Pluta, who at that time worked in the refinery as a driver, remembered: “After the (British) prisoners left the camp, but before the end of August 1944, I received the order for a truck with a trailer. I was in the camp at the time. I was directed to this concentration camp in Brzezinka (Birkenau), where a group of Jewish prisoners dressed in uniforms were loaded onto the truck. The loading of the prisoners took place quickly, with SS men, urging them on and beating the prisoners. How many prisoners were loaded onto the truck, and the trailer, I do not know exactly, in any case there were so many they could not move around at all. In the four corners of the truck, there were SS men with machine guns…..The prisoners had to sit one on the other. We brought these prisoners to the camp abandoned by the English POWs. I was ordered to go again to the Birkenau camp.…. I can add that the first group of Jewish prisoners, were brought to the camp in Trzebionka in the afternoon, and all night, until the second morning – to the camp square …” [10] The prisoners were taken to the abandoned POW camp between the 2nd and 6th August 1944 [11], and the security was enhanced by electrifying the barbed wire fences and adding two guard towers. [12]

A former prisoner, Willy Manela remembered arriving in Trzebinia, “In 1944 I was brought from the Arbeitslager Kielce to Auschwitz and approximately two weeks later was sent to Trzebinia…. In the camp were approximately 300 prisoners from Kielce. Later came many from Litzmannstadt and some later from Hungary.” [13]

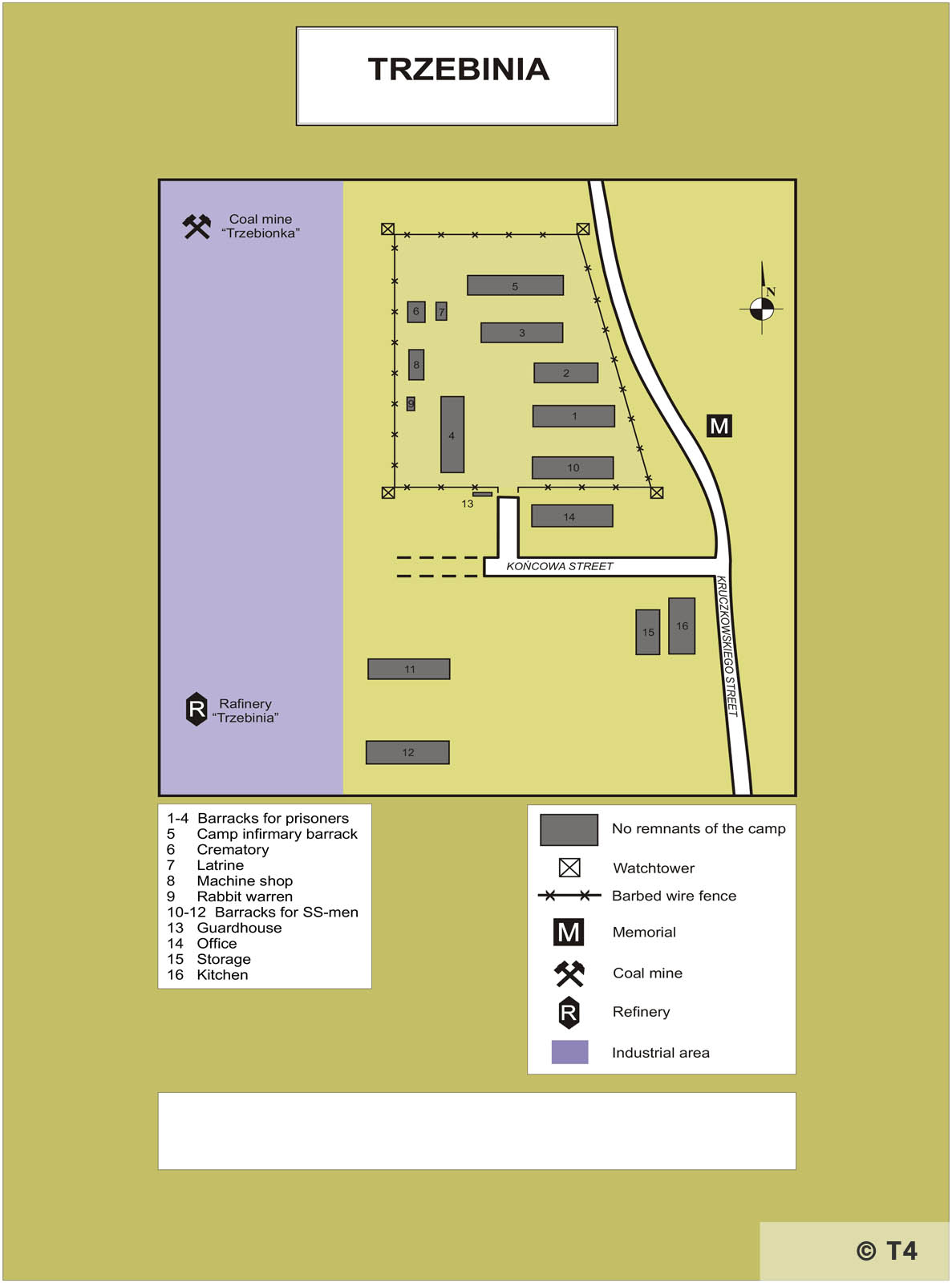

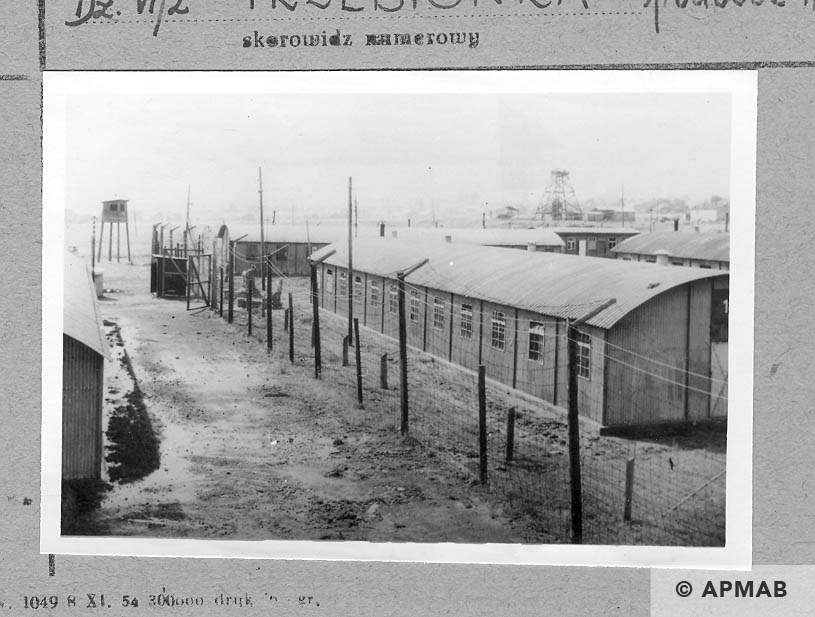

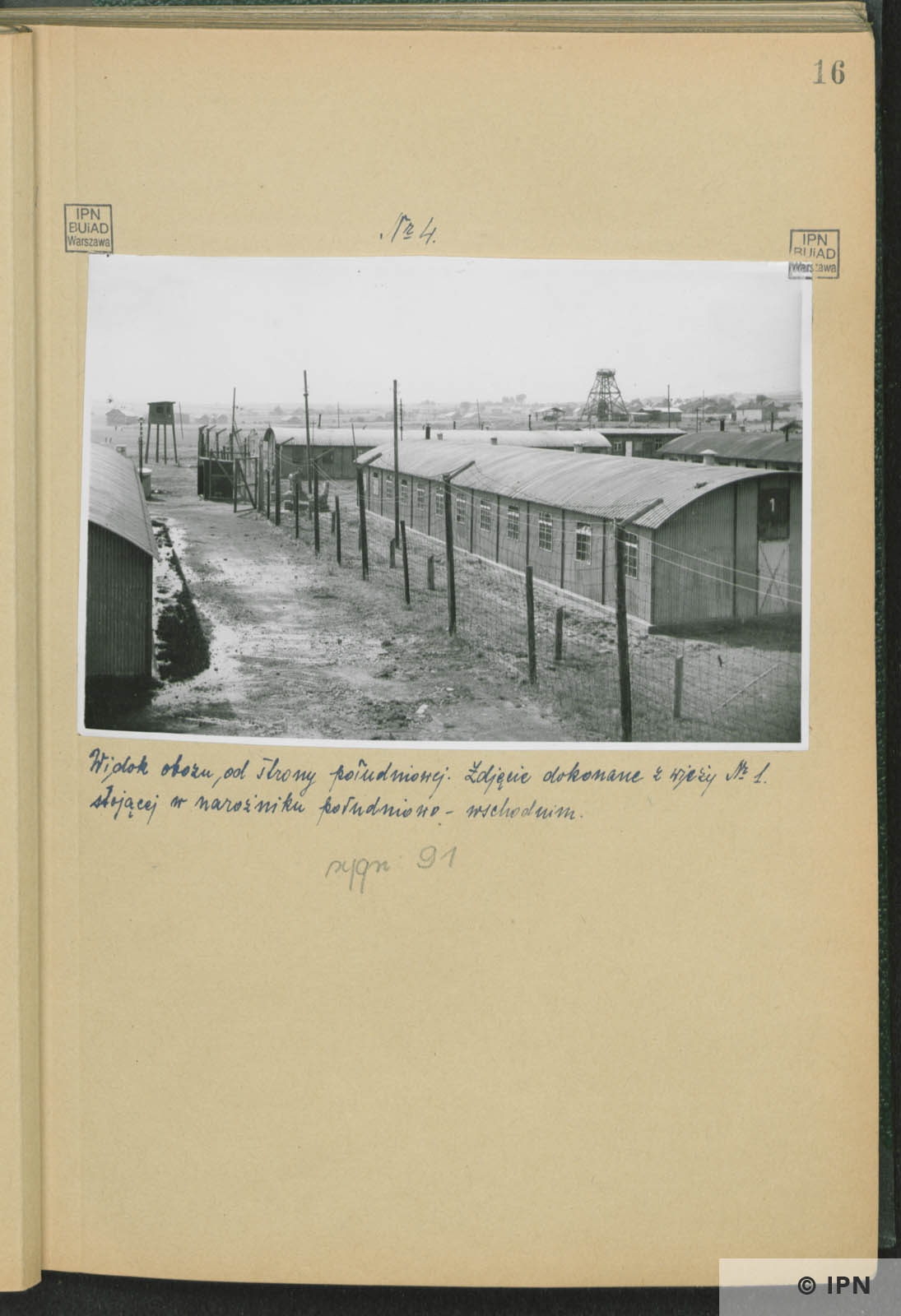

The area of the sub camp in Trzebinia-Trzebionka took the form of a trapeze shape measuring 92 x 100 x 62 x 102 m and occupied about 0.77 hectares. The camp was surrounded with a wooden post fence, about 3 m high, at intervals of approx. 3.5 m. At the top of the posts, the crossbars were nailed diagonally in the direction of the camp. Insulators were mounted on the pillars on the inside and 14 rows of electrified barbed wire were strung between the poles on the outside. Inside the camp, there were also a fence made up of 1 meter wooden posts with barbed wire strung between them. These posts marked the so-called death zone for prisoners, beyond which they could be shot by the guards without warning.

Inside, just next to the fence, there were wooden posts with mounted floodlights illuminating the camp at night. Outside the camp, in the four corners, wooden guard towers were set up and concrete bunkers. In the concrete bunkers SS men could take shelter in the event of an air raid.

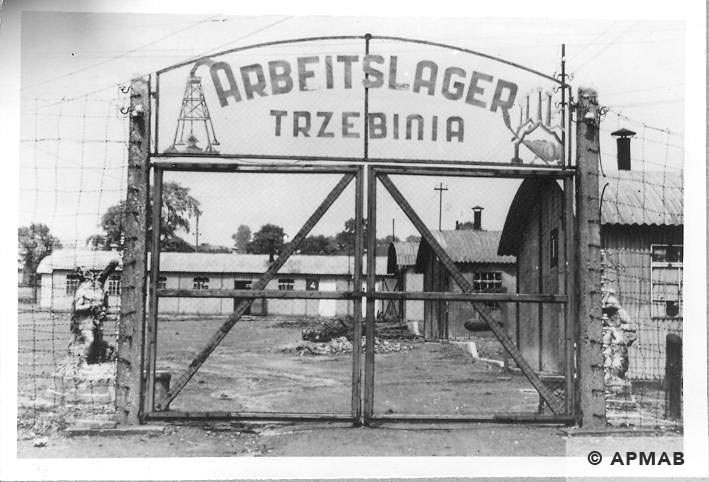

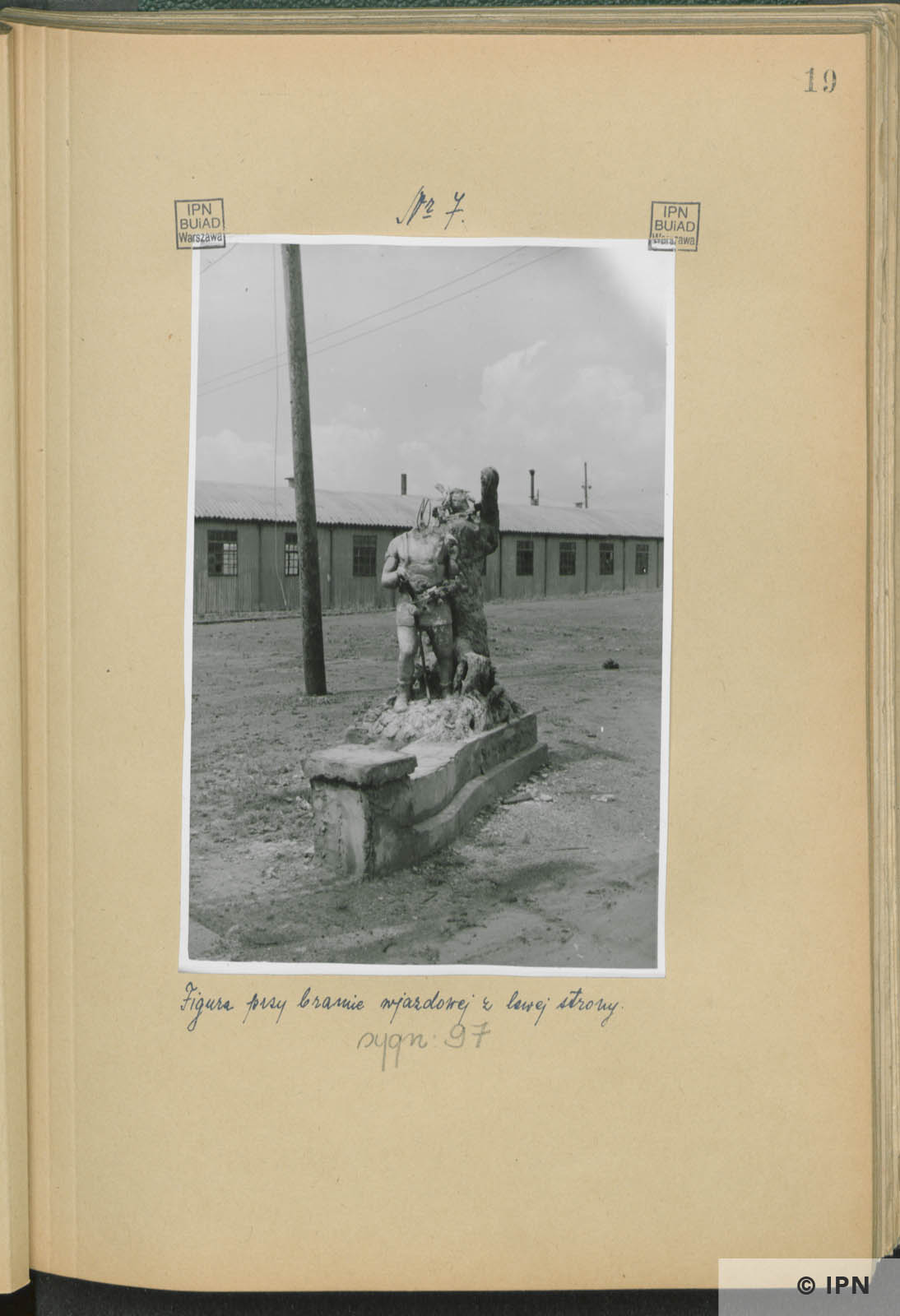

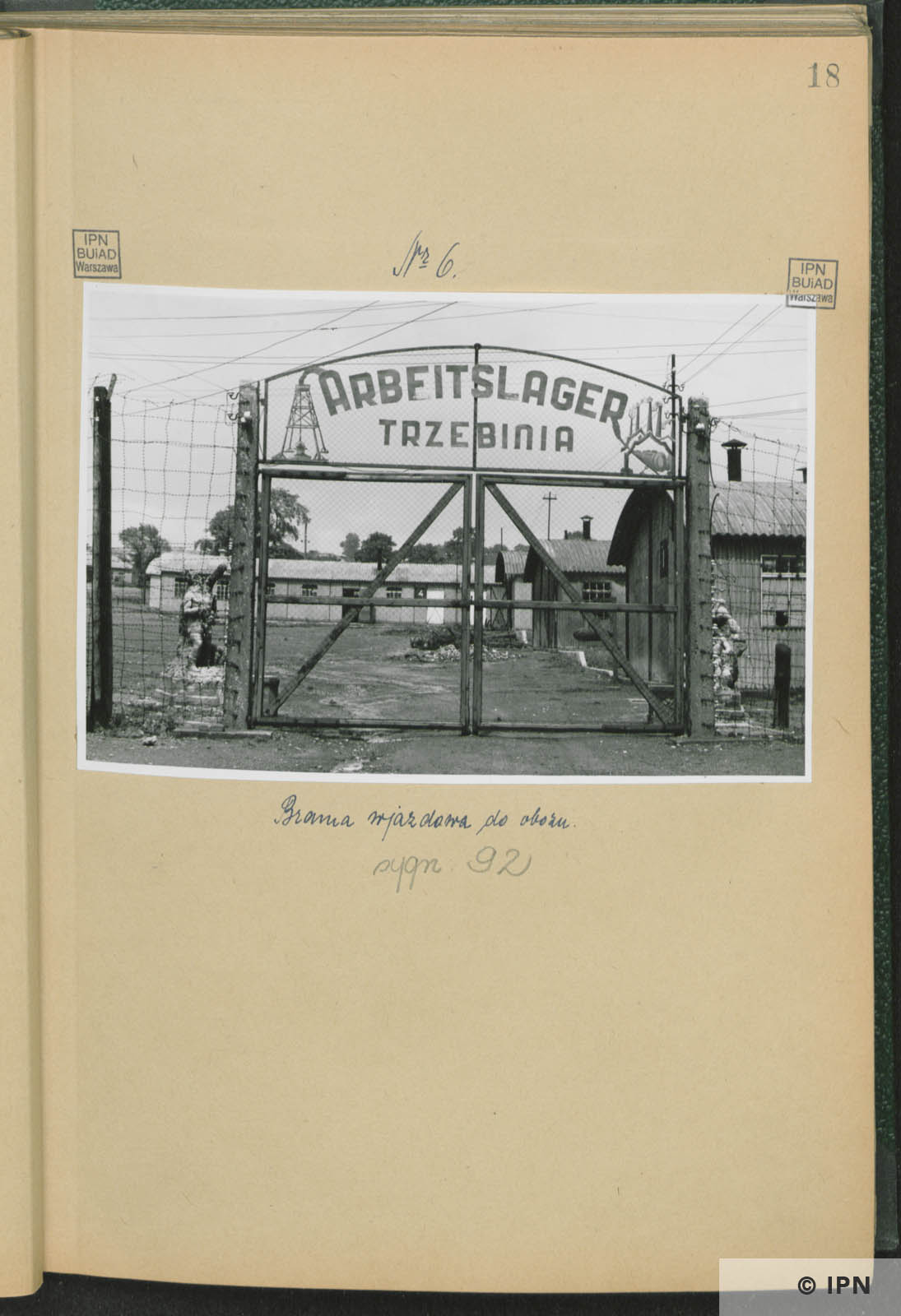

The main entrance to the camp was from the south. This was a double-winged gate built from wooden frames and mounted on concrete pillars. A metal frame at the top of the gates, had a wire mesh pulled across it. A metal inscription “ARBEITSLAGER TRZEBINIA” was attached to the mesh. On the left and right hand sides of the inscription were attached symbols cut from sheet metal. On the left side – an oil drilling tower with gushing oil, on the right – the contours of refinery buildings with smoking chimneys. Unfortunately, it is not known who produced the inscription and symbols hung above the gate. It is also not known who designed and manufactured the two concrete figures drilling oil, standing behind the gate. [14]

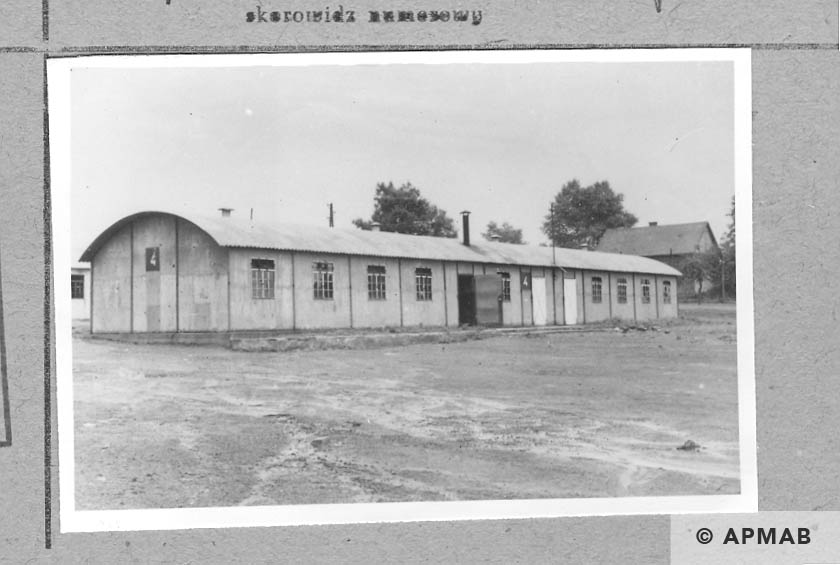

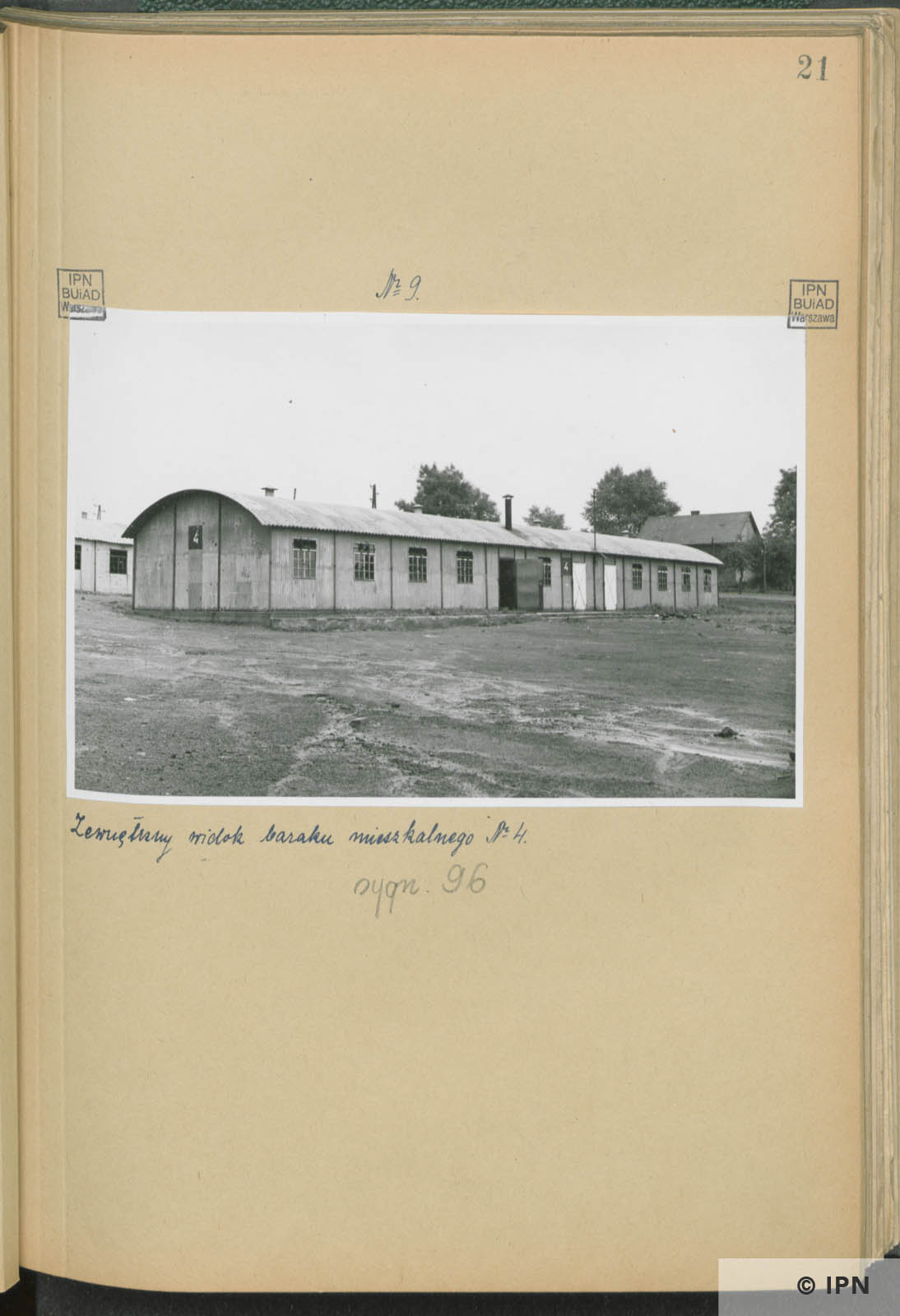

In the sub camp six barracks were built of corrugated iron and covered with an arched roof. The barracks had the same width – 7.6 m, but differed in length. The shortest was 24 m, the average 30 m, while the longest barrack was 35 m long. In all the barracks there were concrete floors, windows, washbasins and running water. The walls of the barracks were lined with cardboard boarding. In order to insulate between the cardboard boarding and the corrugated iron, wool and Staniol were inserted in the gap. Most of the barracks were equipped with coke fuelled central heating. Only two barracks were heated using iron and brick ovens.

Four of the six barracks (map references 1,2,3,4) were intended for prisoners. In the middle of the barracks stood triple level, wooden bunk beds with dimensions: 195 x 80 cm. The spacing between the bunk beds was only 60 cm. There were two boilers in barrack no. 1, used probably for washing linen, while in barrack no. 3 there was a utility room, washrooms and corridors that separated the interior of the barrack into two rooms. The windows in the barracks were barred.

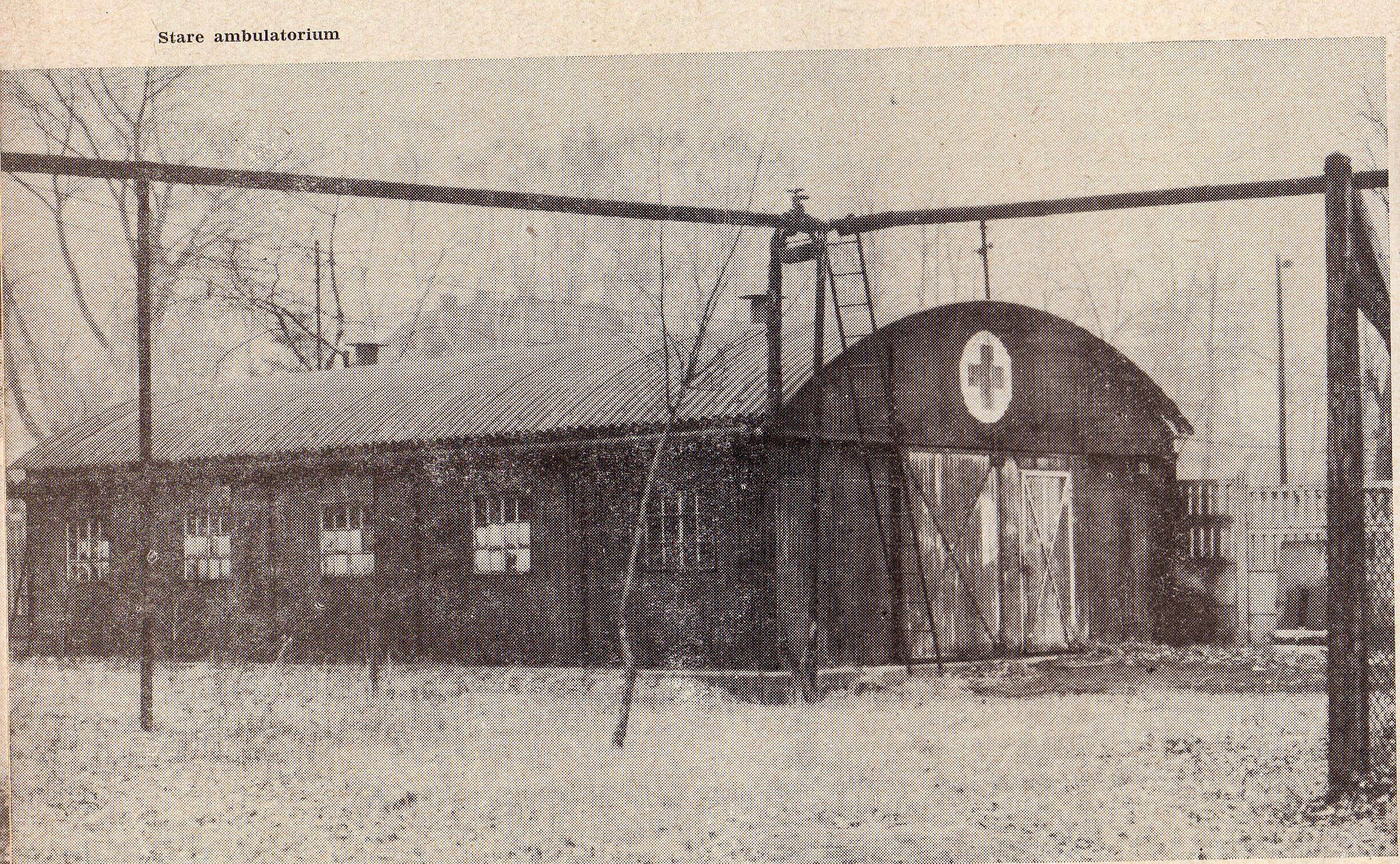

In barrack number 10 there were an office, a shoemaker’s workshop and a dental infirmary. The hospital barrack barrack number 5 housed the infirmary and the nurses‘ room.

In the western part of the sub camp there were a crematorium (map reference 6), a paint and locksmith’s workshop (map reference 8), a rabbit shed (map reference 9) and a latrine (map reference 7). A detailed description of the crematorium is given below.

The remaining sub camp buildings were located outside the fence. In front of the main gate there were two barracks, the guardhouse (map reference 13) and a camp office (Blockführerstube, map reference 14). Further on were the barracks for the SS guards (map references 11, 12), the camp kitchen (map reference 16) and the vegetables storage warehouse where potatoes were also peeled (map reference 15). [15]

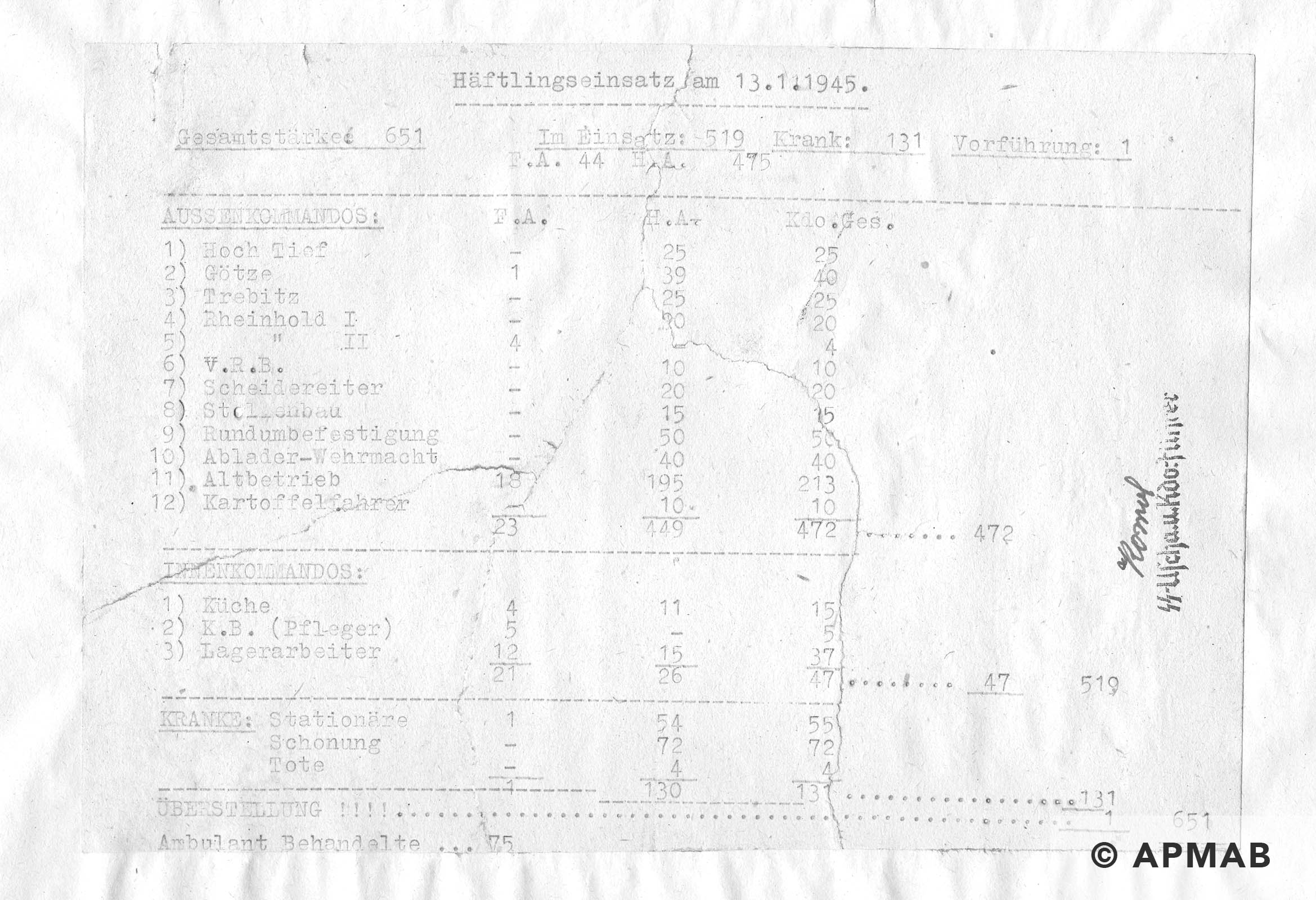

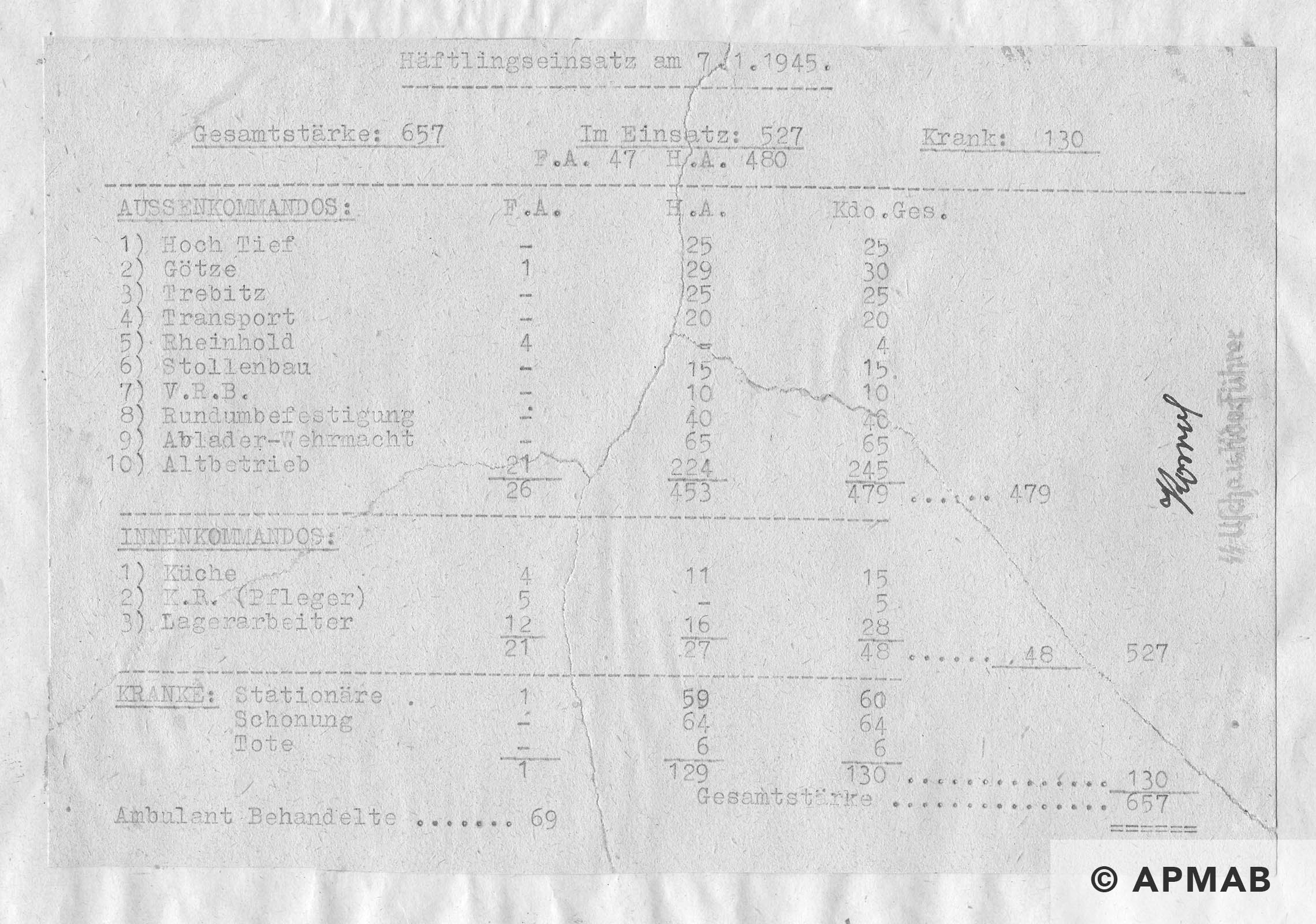

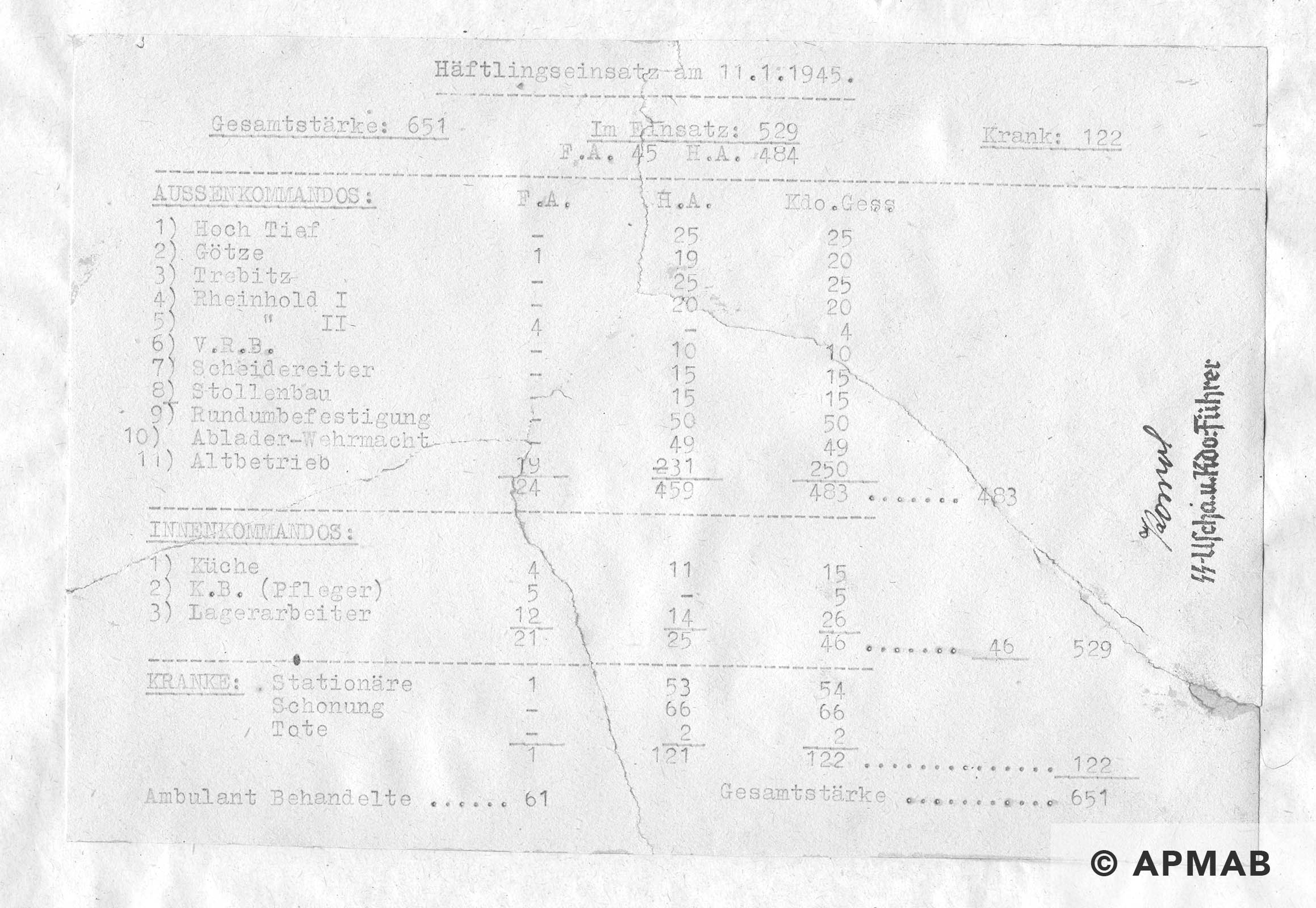

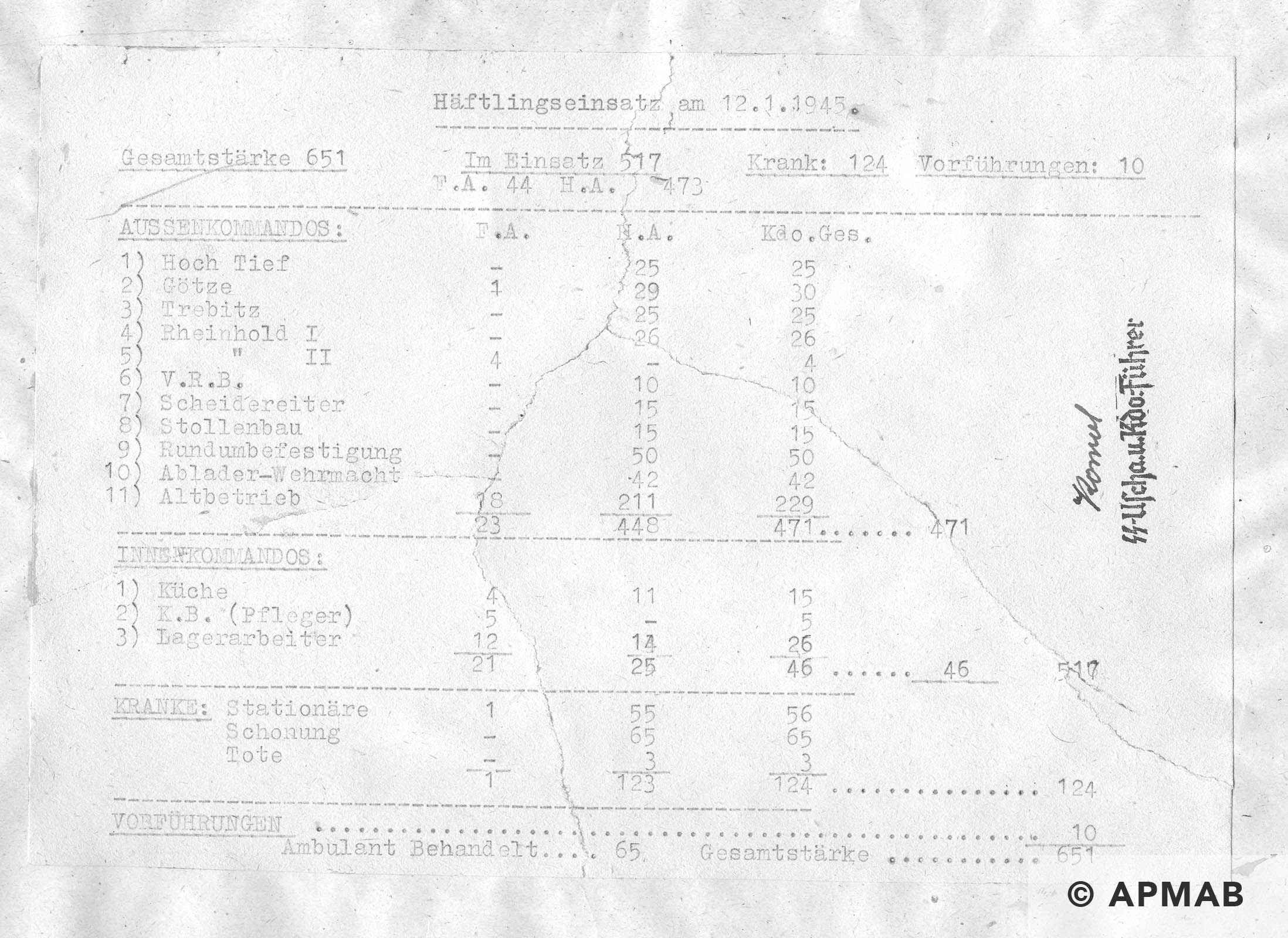

The prisoners began working in the refinery on August 7, 1944. There were 305 prisoners at this time. A week later a further group of 300 prisoners arrived in the sub camp, and on September 17, 1944, another 200 prisoners. The number of prisoners in the Trzebinia sub camp was by then around 800. On the basis of data on the number of prisoners from the monthly reports submitted to Auschwitz III-Monowitz, the number of prisoners during the period of operation of the sub camp were: August – 621, September – 819, October – 800, November – 689. The daily report from the sub camp’s office in January 1945 reported that there were 657 prisoners. [16] The prisoners of the sub camp were mainly Hungarian and Polish Jews. Otto Wolken a former Auschwitz prisoner testified on 22nd June 1945, “After the Germans had fled the camp in January of 1945, we found a prisoner count for all of the Auschwitz camps in the main Schreibstube of the Stammlager. It included the following items on 17 January 1945, on the eve of the final liquidation and evacuation of the camp by the Germans:.. Trzebinia 641…”[17]

The first group of Auschwitz prisoners brought to Trzebinia were employed in the expansion of the camp and cleaning works in the refinery after heavy bombardment by the Allies, which took place on August 7, 1944. [18] The initial transport of prisoners were also used to disarm unexploded bombs, “At the beginning I worked in the Blindgängerkommando (Dud Kommando). We had to dig up the duds from the air attack. They were then disarmed by an officer of engineers or Luftwaffe. As long as I did this work not one was blown up. I did this work for approximately 4 weeks.” [19]

It follows that the first group of prisoners were already in the sub camp in Trzebinia-Trzebionka when the air raid took place, not as previously thought that they arrived after the raid.

After expanding the sub camp the prisoners were employed on construction works at the refinery. This included earthworks, transport, construction of pipelines, sewage and power lines, assembly of industrial chemical equipment, construction of tracks, extension of water supply networks, construction of anti-aircraft bunkers and removal of unexploded bombs.

The tasks of the prisoners were assigned by the management of the refinery, who often loaned them to various construction and assembly companies who worked at the refinery. [20]

Michał Stefański a local resident witnessed the Jewish prisoners at work and how they were treated, “I saw how the Jews were treated both within the camp and at work. They were given different types of work to do. They were put to work building up the plant and unloading goods. They also worked within the camp area. All the tasks which they were given had to be done at pace. They worked from dawn to dusk, and the food they were given was very poor. The Jews I met complained all the time that they were hungry. Wearing nothing but some thin cotton striped uniforms, they suffered great ill-treatment at the hands of SS men and Kapos, which I saw with my own eyes. The Kapos were Germans. I saw them kick and beat the Jews with their hands and sticks without paying any attention to where they were beating them. Those attacked received serious wounds and some of them died. SS men maltreated Jews for no reason at all or for minor offenses.” [21]

The work day was unregulated. It depended on the weather conditions and the decision of the company to whom the prisoners had been seconded. On average, the working day ranged from 8 to 11 hours but the work day was shorter on Sundays. Sometimes the prisoners were allowed to rest on one of the weekdays, however, this did not happen more than once every few weeks.

The refinery’s management complained about the poor efficiency of prisoners‘ work, almost 50% less than that of the civilian workers. Attempts were made to remedy this with bonus vouchers, which were handed out to the most productive prisoners. These could be redeemed in the camp canteen. However, the vouchers had little value to the prisoners as they could not use them to buy good, high calorie food. Therefore, the management of the refinery gradually withdrew this incentive, relying more on increasing discipline and strengthening supervision by the German criminal Kapos.

For the first few weeks, Jews performed the functions of Kapo in the sub camp, but in August 1944 they were exchanged for German Kapos. As a result of this the refinery management reported that the productivity of prisoners improved had improved. [22] The prisoners from the Arbeitslager Trzebinia were treated more harshly. The German Kapos beat the prisoners and tortured them. The most brutal was Oberkapo Albert Gumpricht, who himself killed many prisoners. Józef Woch, who lived near the camp, witnessed the ill-treatment of the prisoners by the German Kapos, “It happened that the kommando returning from their workplace brought the corpses of those who had been killed during the workday. I do not know the names of the Kapos. They were mostly professional criminals – Reichsdeutsche. One day in the evening, I noticed, amongst a group of Jews returning from work, a man aged about 35, who could barely stand on his feet and he fell over on the road in front of the house where I lived. The Oberkapo, a Reichsdeutsch, and who boasted that he had already spent eleven years in prison approached him, beat him with his fists and kicked his legs, asking the abused man if he could go on. The unfortunate man got up and tried to go on. However, he only went as far as the corner of the camp kitchen, where the Oberkapo hit him again so that the prisoner fell again. That’s where his fellow prisoners picked him and brought him to the camp. The next morning I was near the camp. The SS man, who was constantly wandering around the camp (I do not know his name), called me and asked if I wanted pork meat (…). I thought that it would indeed be pork and in the company of this SS man I entered the first block. He led me to the door of one of the rooms and told me to open the door and look into the room. When I did this, I saw in the hall the corpse of the Jew lying on the floor, who the Oberkapo had mistreated the day before. The Oberkapo constantly tormented the prisoners and also beat most of the camp Kapos. He was an older man (…) fat, squat (…) and red in the face. Using his fists he hit the prisoners in the chest. After such punches, the prisoner haemorrhaged from his mouth and nose and usually his life ended.” [23]

Other German Kapos, included: Heinz Wustig, Kurt Fricke, Karl Winderstein, Josef Pickert and Josef Makoviak, who were also characterized by exceptional brutality. Michał Stefański, a resident of Trzebionka, testified after the war: “I saw with my own eyes how SS men and the prisoners who had supervised the other prisoners mercilessly abused Jewish prisoners. The Kapos were German. I saw that – they didn’t care where they beat them – they beat Jews with sticks, their hands and shovels, as a result of which prisoners were injured and in more than one case they died.” [24] A civilian refinery worker – Kazimierz Chrząszcz also witnessed the torturing of prisoners by the Kapos: “The Kapos beat the prisoners with various objects, in particular rubber cables, iron rods, the heads of shovels.” [25]

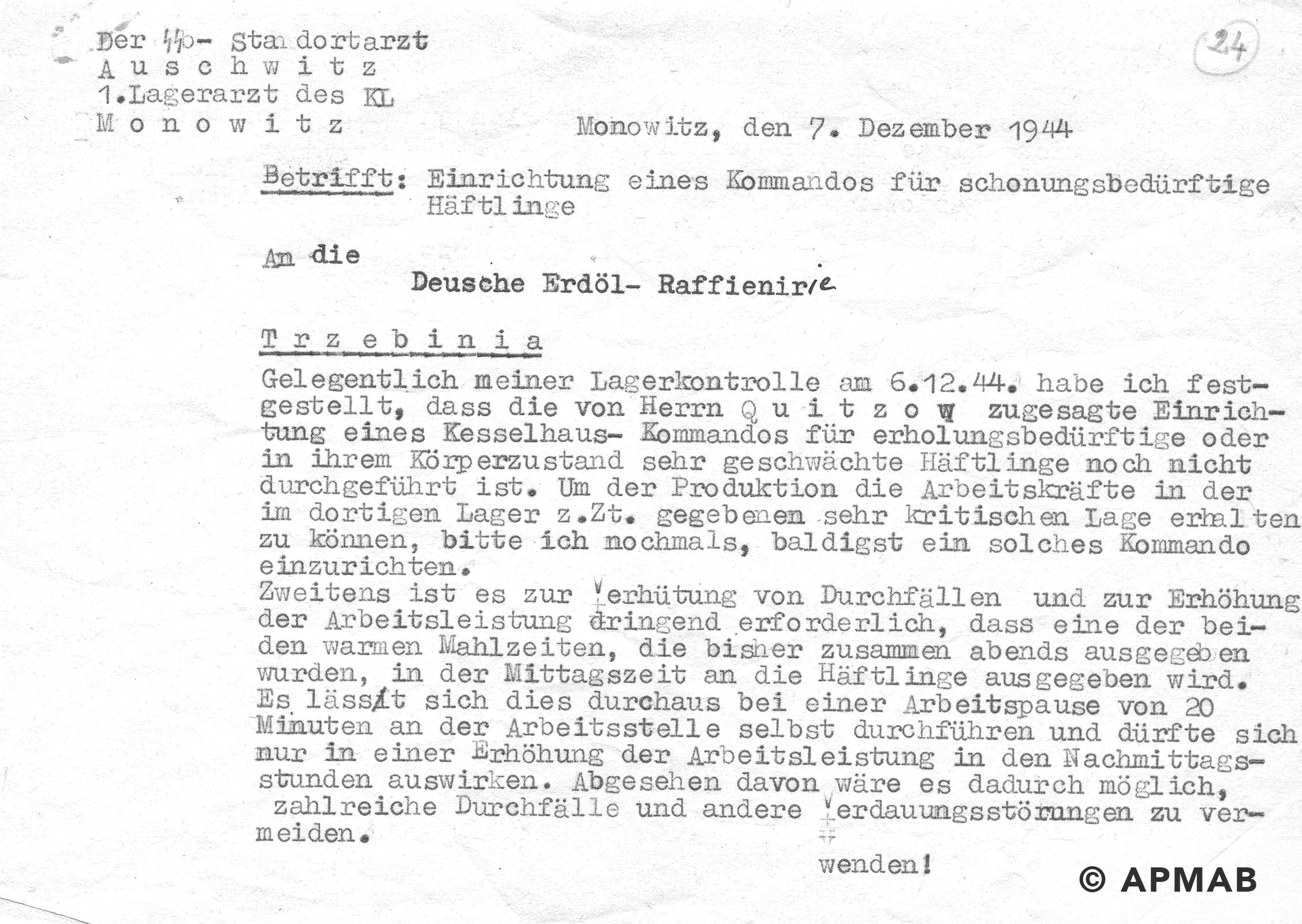

The strict discipline, adopted by the German Kapos did not produce the expected improvement in work efficiency. There was a slight increase in productivity to an estimated 50 – 55% of the standard productivity of the civilian employees, but not the intended increase to 60 – 70%. The low productivity of the prisoners of the Arbeitslager Trzebinia resulted not only from the brutal behaviour of the German Kapos, but also poor health due to malnutrition, exhausting work, and inadequate rest. This led to the increasing numbers of prisoners unable to work. Research conducted by Dr. Franciszek Piper of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum shows that in October and November 1944, 13 to 16% of prisoners on average couldn’t work, but by January 1945 about 170 of the approximately 650 prisoners (29%) couldn’t work. [26] The prisoners were also constantly infested with lice.

Undoubtedly, the main reason for the poor work performance of the prisoners and levels of illness was the poor quality food, which in addition was only provided in small amounts. “The food in the camp was very meagre and insufficient, so the Jews tried to save themselves in such a way that whenever they came into contact with the locals at the refinery, they bought foodstuffs from them and in this way provided themselves with additional nourishment. In the morning, the Jews received coffee and, every two days, bread was distributed. I don’t know how much bread they received. I know, however, that they received bread only once every two days. In the beginning, for about two months, at noon or 13.00 hrs, they would all return to the camp for dinner. Later on, only a few would come and take soup for the rest to their workplace. This soup was made of swede, cabbage or potatoes. In the evenings, after returning from work, the Jews would receive coffee. Special ladles were used to distribute food. Each prisoner received one ladle of coffee or soup. I don’t know how much liquid one ladle contained.” [27]

The camp physician from Auschwitz III-Monowitz during a visit to the sub camp on December 6, 1944, commented on the irregularity of issuing warm meals. [28] Given that the SS and Kapos were also robbing the prisoners of even their meagre food rations, the situation of the prisoners was tragic. Some of the civilian refinery workers, seeing the undernourished prisoners, tried to give them bread directly, or if this was not possible left it in the places where the prisoners worked.[29] Czesława Kalisiewicz, who was employed as a cleaner in the rooms of the SS men and the kitchen testified: “Prisoners who were very exhausted and weakened, and all hungry sometimes stealthily asked for any food and simply threw themselves at the food provided, or food they had found. However, when discovered such incidents were severely punished by the camp Kapos. In particular I once saw that when a Jewish prisoner working near the kitchen came into our kitchen, one of the Kapos with a thick stick hit the Jewish prisoner with all his strength in the head, smashing it.” [30]

The prisoners were dressed in thin denim trousers, a shirt and long johns. In the winter they had coats. On their feet they wore mostly wooden clogs without socks, which in autumn and winter caused painful abrasions and injuries to the legs and feet and also frostbite. For any attempt to warm themselves, by using for example newspapers or paper sacks inserted into their clothing, the prisoners were severely punished.

The sub camp was periodically inspected by Auschwitz III-Monowitz. “Before such an inspection, the camp would be put in order. During such an inspection, all Jews would be lined up at the roll call square where they would have a speech delivered to them and be beaten.” [31]

Incapacitated prisoners were sent to Auschwitz II-Birkenau or Auschwitz III-Monowitz where they died in the overcrowded hospital blocks or were immediately killed in the gas chambers. As a result of increasing mortality, a crematorium was built in the sub camp. [32]

[1] These were: 1) Kommando E 565 Stalag VIII B Lamsdorf (Outside working party of prisoners from the British POW camp Łambinowice), which existed from 1943 to 10 January 1945, numbered about 120 prisoners who worked in the mine „Arthurgrube“, 2) Kommando E 738 Stalag VIII B Teschen (Branch of the British prisoners working in Cieczynie), which existed from November 1943 to August 1944 and had about 200-300 prisoners working in the refinery, 3) A labour camp for Jewish women founded in 1943, closed in 1944 which numbered around 60 and worked in the maintenance of roads and water supply, 4) A labour camp for Jews founded in 1942, and closed January 20, 1945, holding approximately 800 prisoners, and 5) A police custody camp (Polizeigefängnis) having the status of a penal camp for Poles and Jews, who were employed in the construction of roads, snow removal, loading and unloading, and other public works. The labour camps for Jews were part of Organization Schmelt headquartered in Sosnowiec. Information: Vorläufiges Verzeichnis der Konzentrationslager und deren Außenkommmandos sowie anderer Haftstätten unter dem Reichsführer-SS in Deutschland und deutsch besetzten Gebieten (1933-1945), Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, International Tracing Service, Arolsen 1969, Verzeichnis der haftstätten unter dem Reichsführer-SS. Konzentrationslager und deren Außenkommmandos sowie anderer Haftstätten unter dem Reichsführer-SS in Deutschland und deutsch besetzten Gebieten (1933-1945), Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, International Tracing Service, Arolsen 1979 and Obozy hitlerowskie na ziemiach polskich 1939-1945. Informator encyklopedyczny, Warszawa 1979.

[2] Erdöl Raffinerie Trzebinia O/S.

[3] Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 153-190.

[4] Testimony of Michał Stefański 28 June 1954. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content

[5] There was British Prisoner of War Working Party E738 from Stalag VIIIB 344 Lamsdorf in Trzebinia ( https://www.lamsdorf.com/working-parties.html).

[6] Probably not construction, but redevelopment of infrastructure already existing there. According to the research of Dr. Franciszek Piper there already existed barracks for civilian workers from Belgium.

[7] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of Władysław Mendela, Vol. 48, p. 62.

[8] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of Władysław Mendela, Vol. 48, p. 62.

[9] APMAB. Zespół Trzebinia, Vol. 3, section 2, p. 44.

[10] Stanisław Pluta witness statements filed on 16 October 1968 at OKBZH in Krakow. See also: Franciszek Piper, Podobóz Trzebinia…, p. 170-171.

[11] Piper, Franciszek Podobóz Trzebinia…, p. 155.

[12] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of Władysław Mendela, Vol. 48, p. 63.

[13] StA Bremen 48913-1026 testimony of Willy Manela.

[14] The photograph of the camp gate of Arbeitslager Trzebinia taken in 1945 during the investigation carried out by members GKBZNwP has become an icon of the Auschwitz sub-camps and the forced labour camps in general. Undoubtedly, Spielberg´s Schindler’s List used the gate of the sub-camp Trzebionka-Trzebinia as a template for the representation of the gate of Arbeitslager Plaszow in the film. It is not known exactly what happened to the original gate of the sub camp Trzebionka-Trzebinia.

[15] The description of the sub camp is based on the following sources : a) Franciszek Piper, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 156 – 162; b) The protocol of inspection conducted on 27-28 June and 13 July 1945 by members of GKBZNwP, Jan Sehn and Edward Pęchalski and Professor Roman Dawidowski, APMAB, Proces Załogi, vol. 62, p. 1-10; c) The testimony of Leon Dadak, AMPAB, Zespół Oświadczenia, Vol. 48, p. 66-67 and d) the analysis of the photographs of the subcamp in Trzebinia in Archives of Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and IPN.

[16] See: APMAB. Zespół Trzebinia, Vol. 3/2, p. 29, 15, 3, 2. APMAB. Zespół Trzebinia, Vol. 3a/5, p. 1-9 and analysis of the employment of prisoners in the sub-camp in Trzebionka-Trzebinia in Franciszek Piper, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 171 – 172.

[17] Testimony of Otto Wolken. Testimony viewed 9 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3755/edition/3736/.

[18] The bombardment of the Trzebinia oil refinery took place on 7 August 1944, under the codename „Frantic 5”. The U.S. 8th Army Air, departed England on August 6 1944, made up of 75 B-17 Flying Fortresses, escorted by 64 P-51 Mustangs, took off from England. Their target was the Focke Wulf plant in Rumia near Gdynia, where 103 tons of bombs were dropped. After the mission the Americans landed at bases provided by the USSR in the Ukraine (Poltava, Piriatyń, Mirgorod). The next day 7 August 1944, 60 Flying Fortresses escorted by 36 Mustangs took off from these bases and raided the Trzebinia oil refinery and then returned to the Ukraine. The next day, the planes flew to bases in Italy bombing on route Buzau in Romania. They took off from Italy for their bases in England on August 12, 1944 on route destroying the airport in Toulouse.

[19] StA Bremen 48913-1026. Testimony of Willy Manela.

[20] The list of companies to which prisoners of Arbeitslager Trzebinia were seconded, is based on research by Franciszek Piper, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 166 – 167.

[21] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of Władysław Mendela, Vol. 48, p. 62.

[22] Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 175.

[23] APMAB. Proces Załogi, testimony of Józef Woch, Vol. 63, p. 36 – 45.

[24] APMAB. Proces Załogi, testimony of Michał Stefański, Vol. 63, p. 30 – 35.

[25] Testimony of Kazimierz Chrząszcz made on 5 May 1969 for OKBZH in Krakow in: Franciszek Piper, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 176.

[26] Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 178.

[27] Testimony of Józef Woch 27 June 1945. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content

[28] APMAB. Zespół Trzebinia, Vol. 3/2, p. 5.

[29] This is confirmed by the testimony of a former prisoner Benjamin Pilicer given in 1958 to Yad Vashem, a copy of which is located in the archives of APMAB.

[30] Testimony of Czeslawa Kalisiewicz filed on 11 April 1969 with the OKBZH in Krakow. Quoted by: Franciszek Piper, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 180.

[31] Testimony of Józef Woch 27 June 1945. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content.

[32] Dr. Franciszek Piper in his research has estimated the number of prisoners killed or who died in Arbeitslager Trzebinia at about 200.

Literature:

Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 153-190.

The SS Guard Unit

The commandant of the sub camp in Trzebinia-Trzebionka was SS-Unterscharführer Wilhelm Kowol. Kowol a Volksdeutsche from Tarnowskie Góry had previously served as a platoon leader in the Polish army. [1] He was remembered by former prisoner Arnošt Tauber: “Lagerführer Kowol was an uneducated and primitive man (…) on his orders I had to arrange his business and private correspondence. Kowol knew little German, and his only concern was getting alcohol. When drunk, Kowol was very dangerous and aggressive, and then he treated the Jewish prisoners barbarously.” [2]

The SS guard unit in Trzebinia numbered about 70 men. [3] Kowol and the SS Guards were bribed by the Jewish prisoners with the help of local Polish residents, “The Jews themselves told me that the conditions in this camp were better than in others, as they had been brought there not to be exterminated, but used as a workforce. Moreover, they tried to ingratiate themselves with the camp commandant, Kowol, whom they gave various bribes with that aim in mind. I myself bought a 10,000 Reichsmarks harmonica for the Jews, which they then presented to Kowol. In order for me to be able to buy it, the Jews gave me a diamond ring. Some other time I bought them a violin, which they also gave to Kowol as a gift. As a result, Kowol himself was not particularly intent on “finishing off” the Jews. As for the other SS men, they were also corruptible, all the more so – as I learned myself, since they used to drop in on me quite often – because they frequently complained about the Nazi regime themselves, which I found rather astonishing in those who wore the SS uniform. One of them told me that the majority of SS men from the garrison in the labour camp in Trzebionka were of the same mind, that they were anti-Nazi, and joined the party only because it provided them with the opportunity to hide and mask their true beliefs. There weren’t many SS men in the labour camp in Trzebionka who would go through fire and water for Hitler, and the rest steered clear of them.” [4]

[1] Testimony of Józef Woch 27 June 1945. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content.

[2] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of former prisoner Arnošt Tauber, Vol. 61, p. 211.

[3] Testimony of Józef Woch 27 June 1945. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content.

[4] Testimony of Józef Woch 27 June 1945. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content.

Literature:

Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 153-190.

The SS Guards

References:

Zppw-auschwitz.pl Zwiazek Polaków Pomordowanych w Auschwitz. List of 8,500 SS men in KL Auschwitz.

BA Ludwigsburg B162/2679 and B162/2680.

IPN database of Auschwitz SS guards. https://truthaboutcamps.eu/th/form/60,Zaloga-SS-KL-Auschwitz.html.

Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Trzebinia, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 153-190.

Piper, Franciszek, Das Nebenlager Trzebinia, [in:] Hefte Von Auschwitz [1978] Nr 16, p. 93-135.

The Crematorium in the Sub Camp Arbeitslager Trzebinia

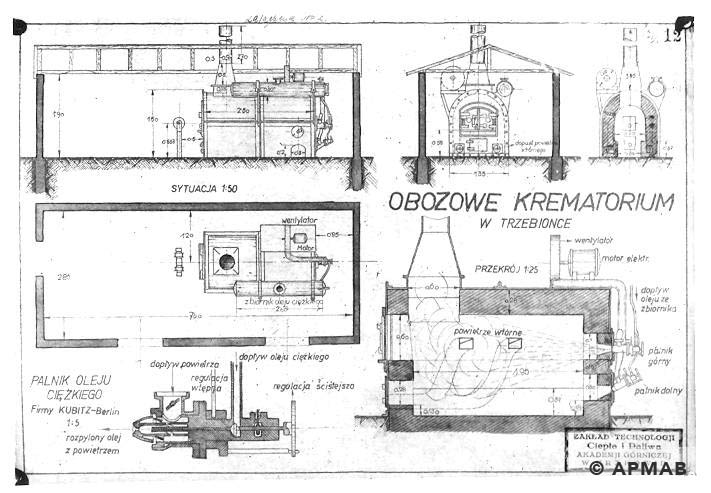

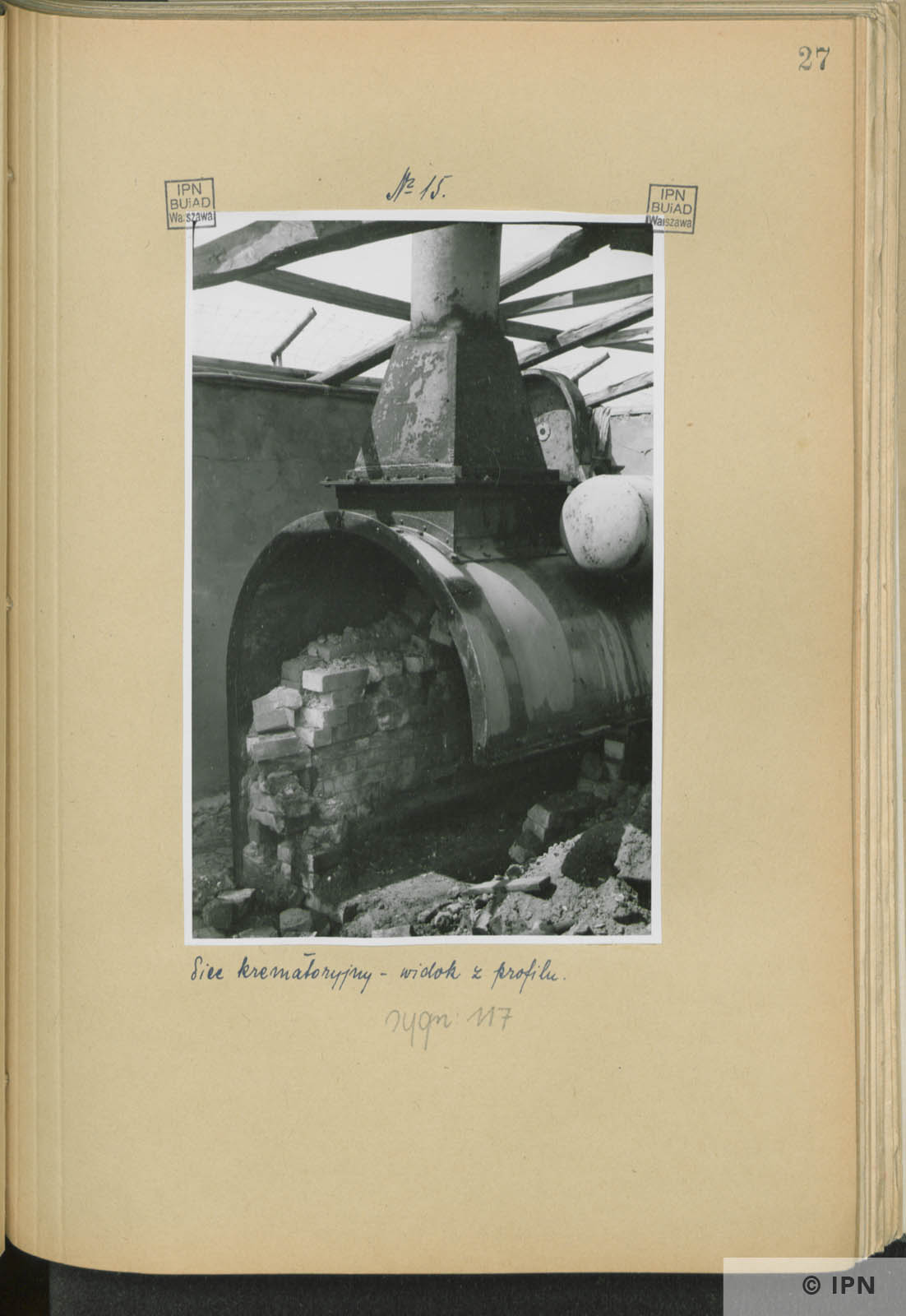

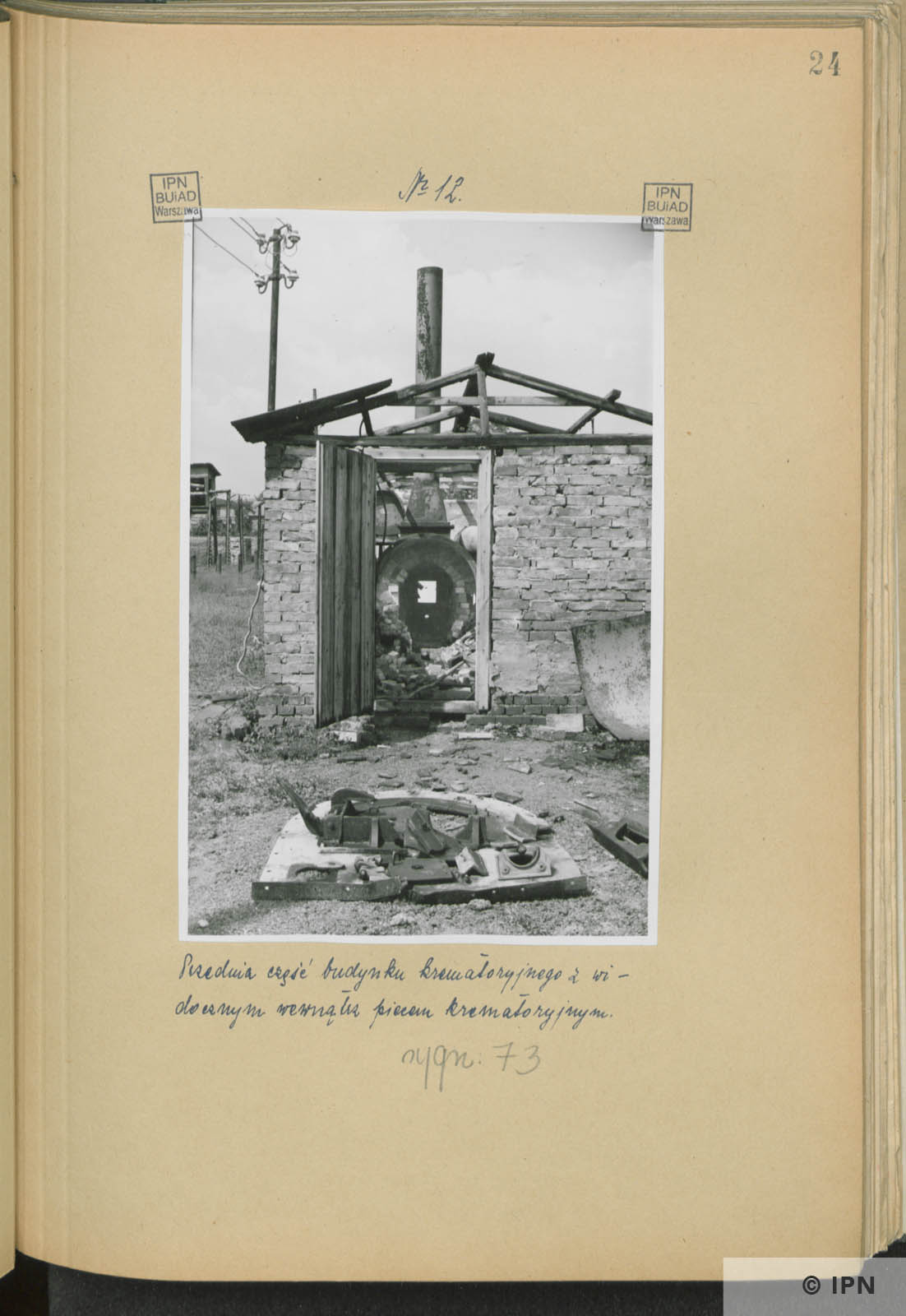

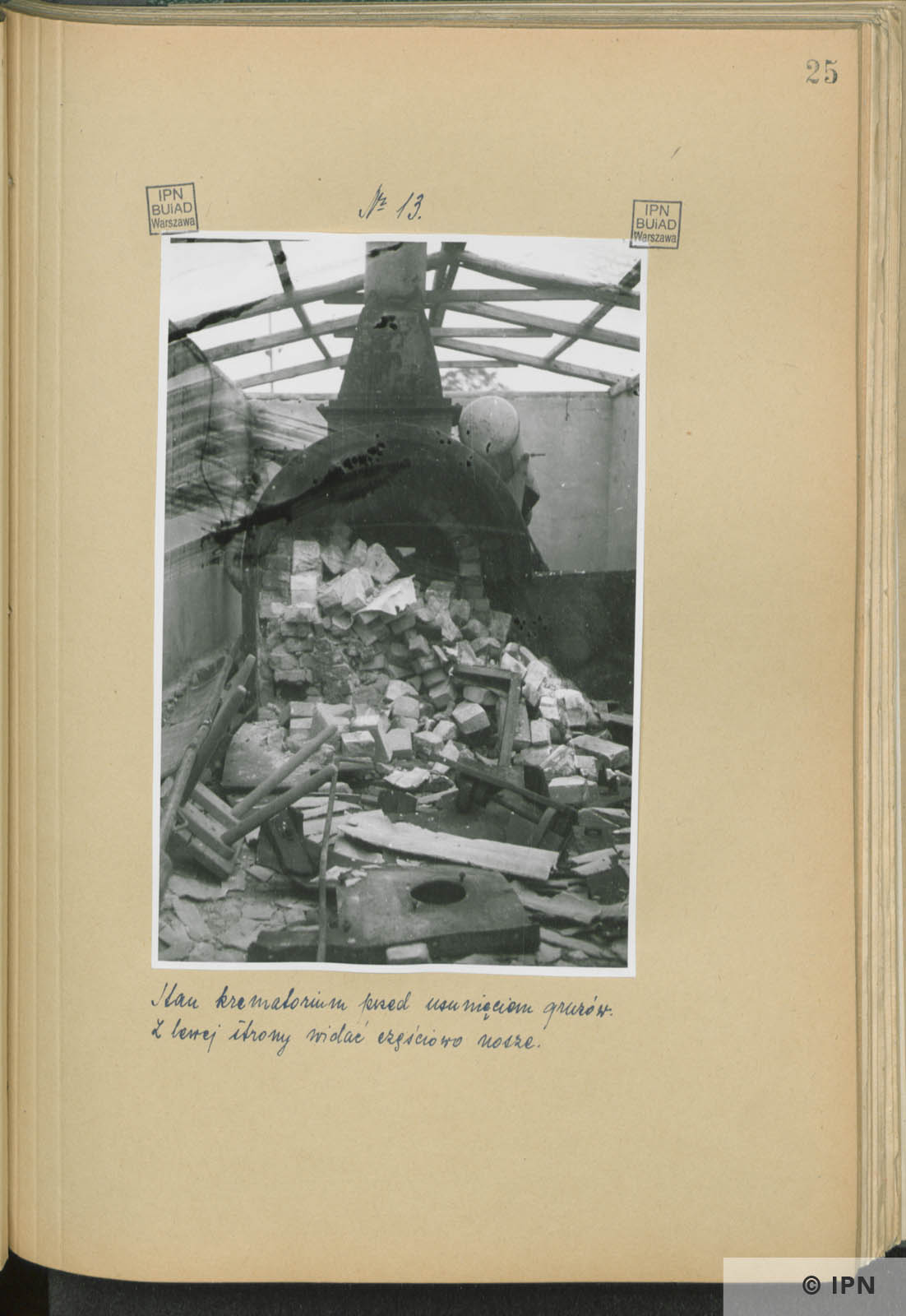

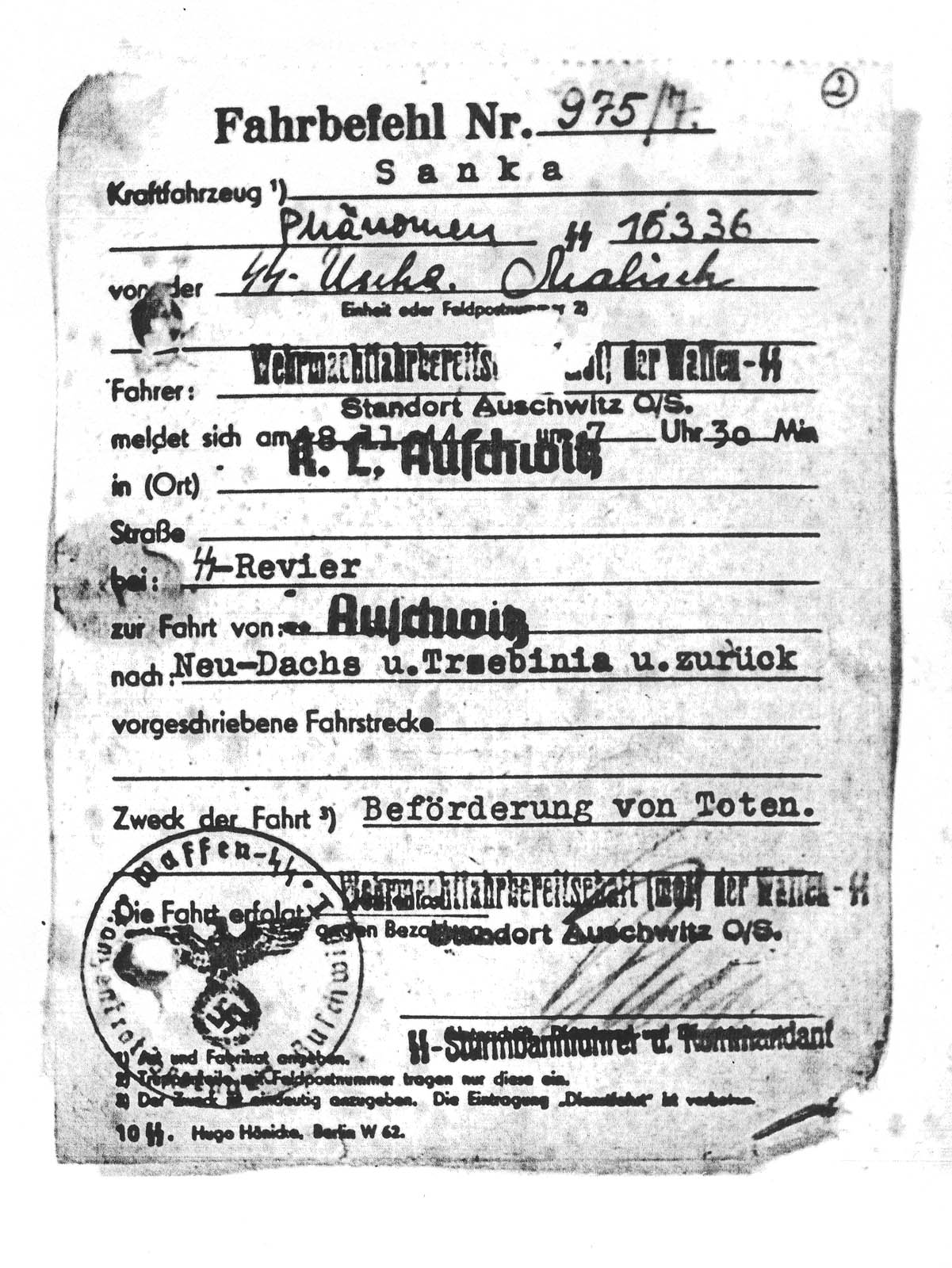

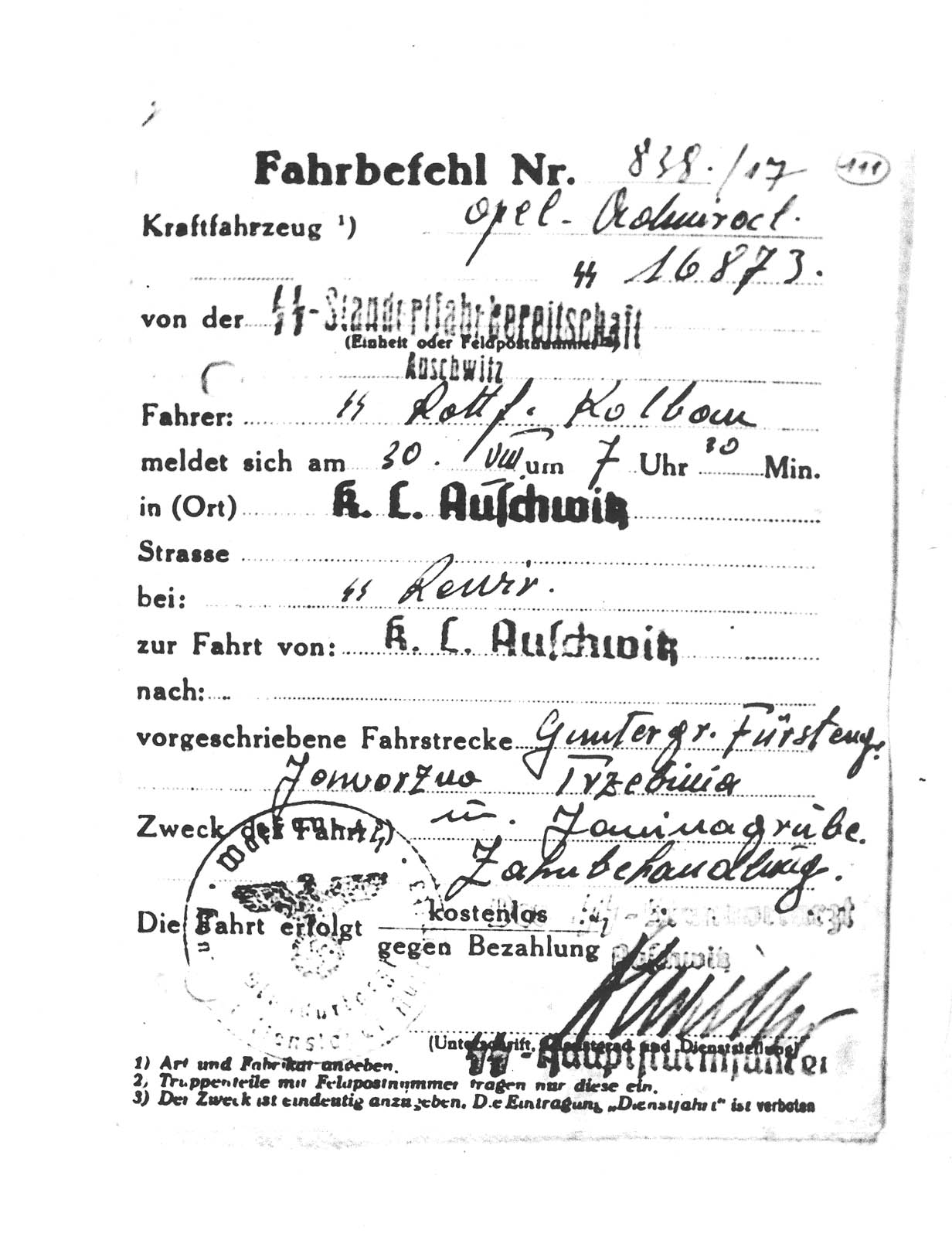

The crematorium in the Trzebinia sub camp was built in the autumn of 1944. Undoubtedly, this was related to SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler’s order of November 26, 1944, for the dismantling of the installations and the complete destruction of the crematoria buildings in Auschwitz II-Birkenau and the increasing death rate in the Trzebinia sub camp. The exact date the crematorium in the sub camp in Trzebinia began operating has not been determined. Witness Michał Stefański, a resident of Trzebionka, testified that the crematorium had already begun operation in October 1944.[1] Dr. Franciszek Piper, on the other hand, believes that the crematorium began operations after November 18, 1944, based on the last preserved order for the transport of corpses from Auschwitz to Trzebinia [2] Dr. Piper’s date is considered the most likely.

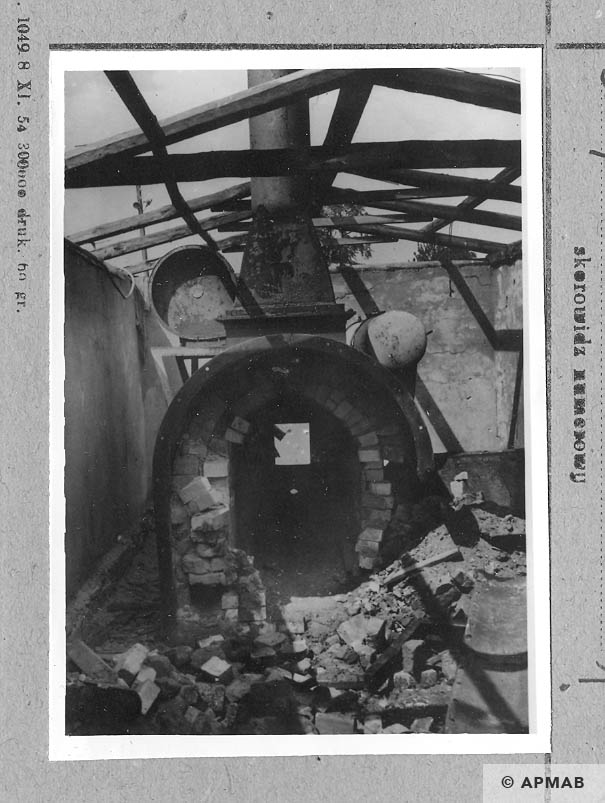

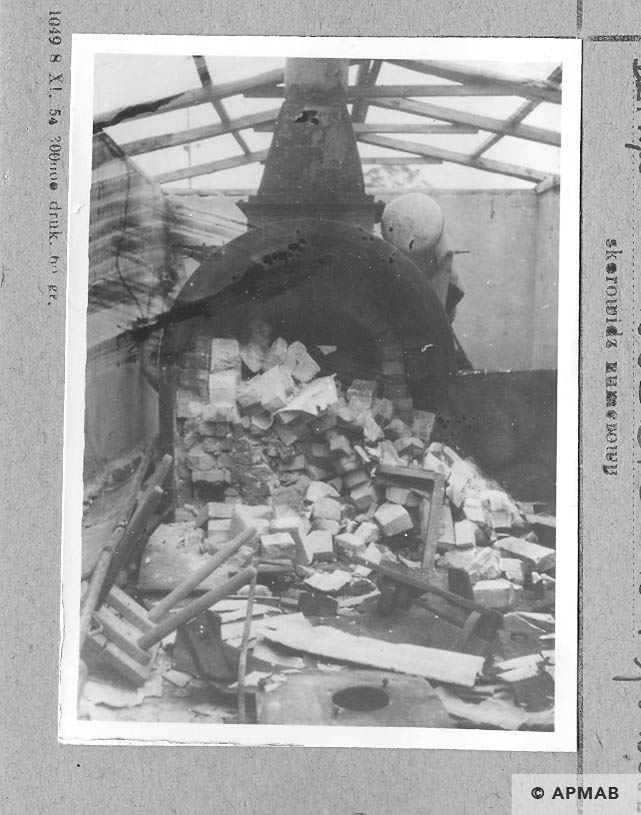

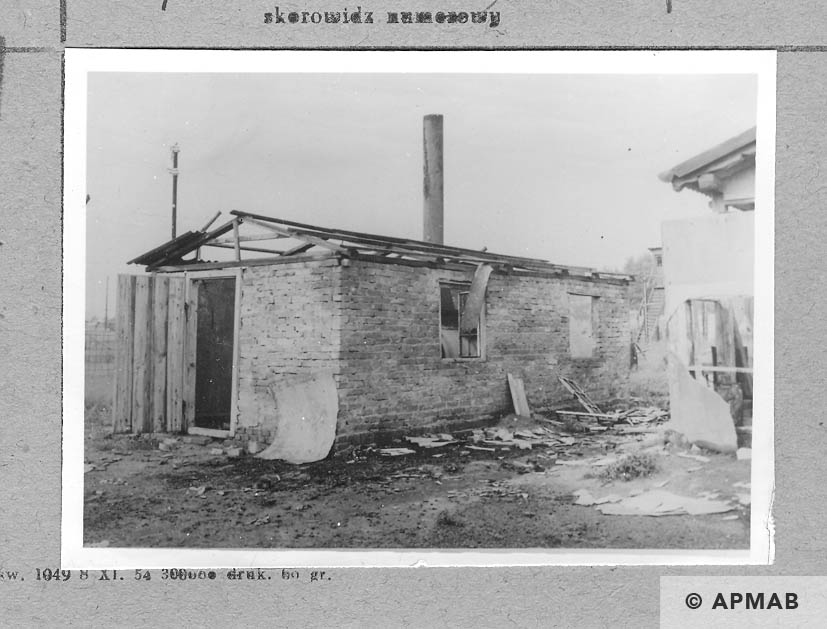

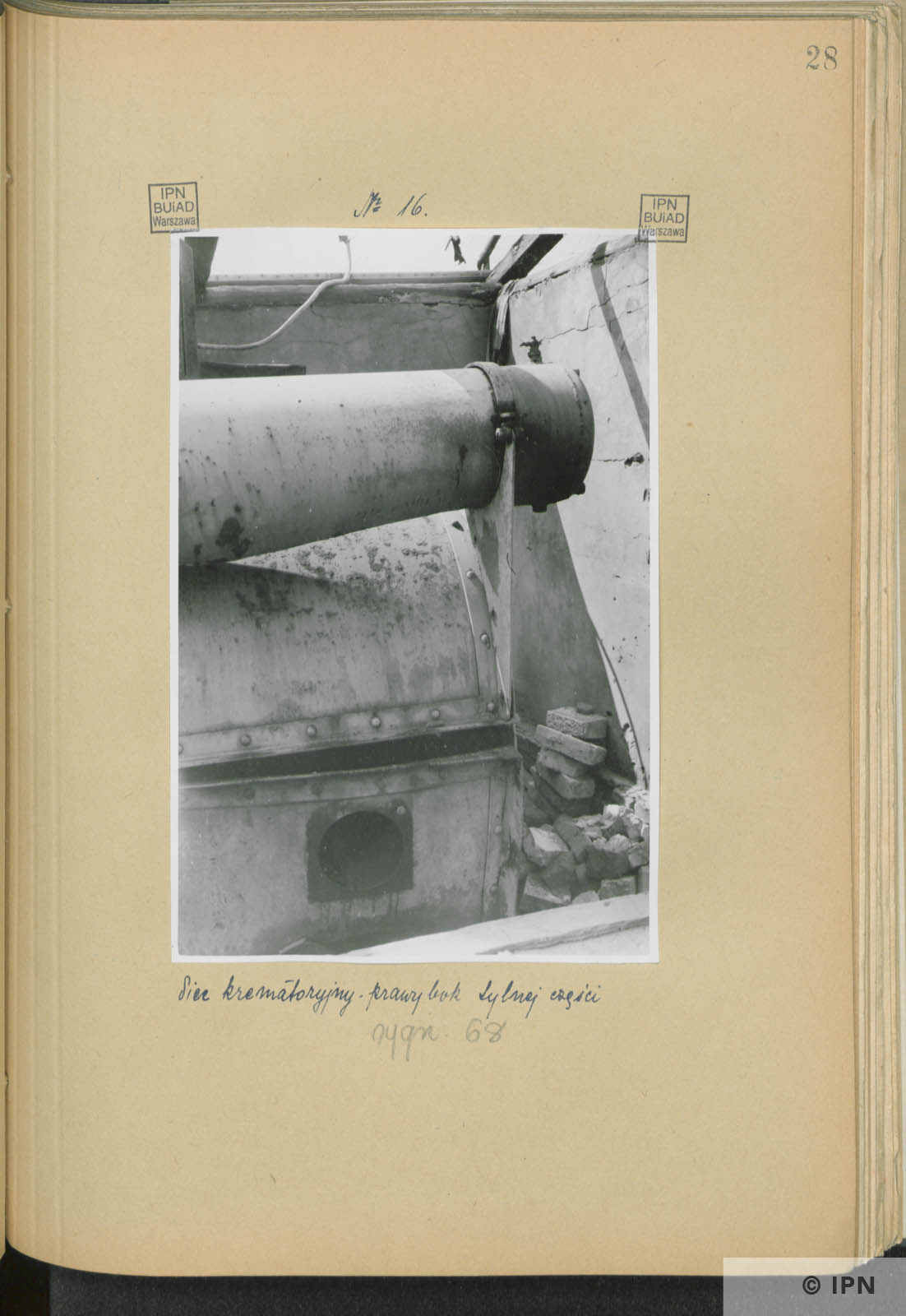

The furnace in Trzebinia was built in a small brick building with the dimensions: 7 m length and 3 m width. The surviving photographs show that the building was hurriedly constructed as evidenced by the poor quality bricks sloppily put together with mortar. It can be assumed that firstly the furnace was delivered, and then it was enclosed by the building with walls of about 2 m height. The building was covered with a gable roof, the top of which was about 0.5 m above the edge of the wall. In this way, quite a large ventilation space was created in this small building. There were two windows on the eastern wall. The wooden entrance door to the crematorium was placed in front end of the furnace. The furnace mounted on foundations was located in the rear left corner. Thanks to this position of the furnace, the necessary space for the operations of loading bodies was obtained. A round tin chimney protruded from the left side of the roof. It was about 1.5 m above the roof and its total length was about 3 m. The crematorium building was thus of a relatively primitive construction, built hastily for the cremation of the dead of the sub camp in the dying days of the war. The crematorium built in Arbeitslager Trzebinia was possibly the last crematorium built in the Nazi concentration camp system.[3] The supervisor of the crematorium in the subcamp Trzebinia was SS-Schütze Julius Hampel.[4]

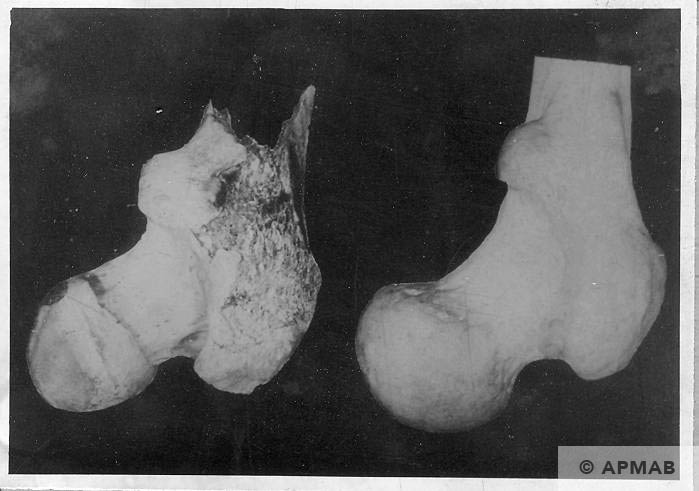

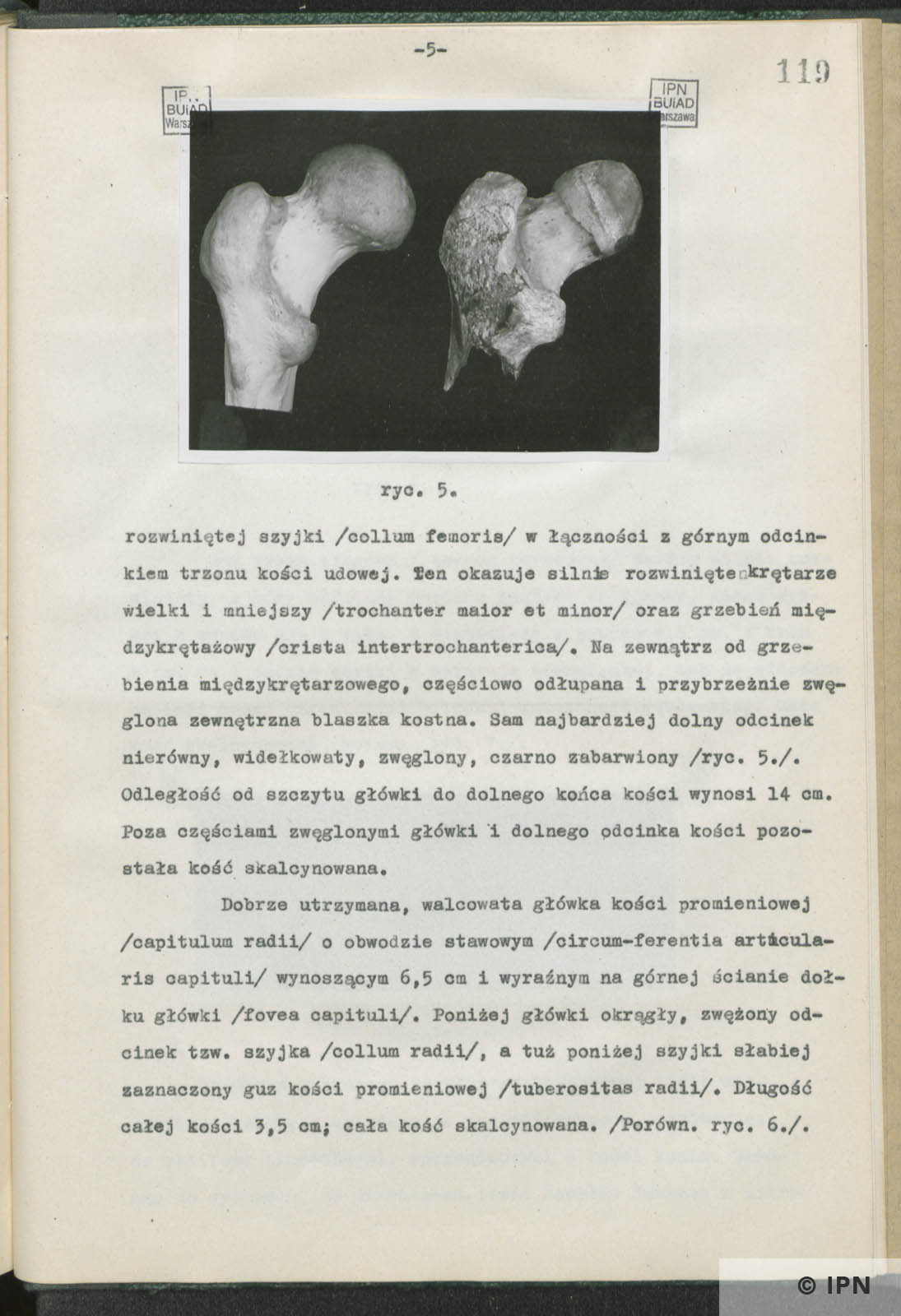

The crematorium furnace used in the Trzebinia sub-camp built by H. Kori G.m.b.H. of Berlin[5] was identical to the one used in the Auschwitz sub camp Blechhammer. The interior of the crematorium was lined with a chamotte brick lining and secured with sheet metal. The corpses were put inside the muffle using stretchers made of iron supported on rolls and fixed in front of the oven at the height of the muffle. The fuel for burning the corpses was mazut, placed in a tank fastened to the right of the main body of the furnace. The oil ran to the two burners installed on the back wall of the furnace, where it was sprayed in the form of an aerosol by means of a strong stream of air forced through the fan by a nozzle. Prior to this operation, however, it was necessary to light the furnace using coke.

It was not an “efficient” device. Józef Woch testified: “Around December 1944, one of the Jewish prisoners who worked in the camp office told me that in the crematorium so far about 20 corpses had been burned.”[6] Research conducted by Dr. Igor Bartosik of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum calculated, the time to burn one corpse was around 20 minutes, with a theoretical capacity of about 72 corpses per day.

There was little secrecy on the use of a crematorium in the camp amongst the local population. Józef Woch, a local resident testified, “At first, the bodies of the Jews were sent to Auschwitz, but later, they were burned in the local crematorium, which was built on the camp premises in the autumn of 1944. I don’t know from where the various parts of the crematorium were brought in or which company fulfilled the order. I once had a chance to visit the camp premises, where I was taken at night by an SS man with whom I was on amicable terms; at the time the rest of the SS men were having a party in their block. Then this SS man showed me the outside of the crematorium and opened the upper iron door through which the bodies were placed in the furnace. I saw coke blazing in it. The SS man told me that in a moment a body would be incinerated in these flames. That, however, I did not see. I am presently unable to say whether there were grates in the furnace nor can I describe it in detail.” [7]

Soon after the camp was evacuated, the commander of the local police (or gendarmerie) Bogusch blew up the crematorium.[8] Michał Stefański remembered the crematorium and its destruction, “I know that before they left Trzebionka the Germans tried to blow up the camp but, for some reason, they failed to carry out the plan and destroyed only the crematorium.” [9]

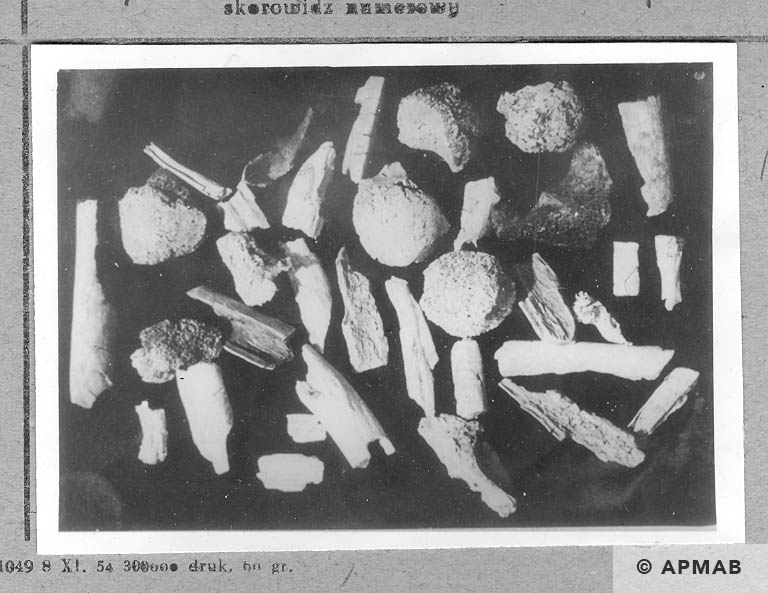

During the inspection carried out by the District Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes on August 5, 1945 of the sub camp Trzebinia, the damaged crematorium furnace was discovered and also numerous unburnt human bones.

The crematorium furnace was subsequently secured and transported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, where it was originally placed in one of the rooms of Crematorium I in the main camp (Auschwitz I). Currently, this furnace is not presented at the exhibition and is kept in a storage room.

[1] APMAB. Proces Załogi ZO Vol. 62, testimony of Michał Stefański, Vol. 35.

[2] AMPAB. Zespół Fahrbefehle Nr 915/7.

[3] APMAB. Igor Bartosik, Zacieranie zbrodni w nazistowskich obozach koncentracyjnych. Technika-procedura-ludzie, Krakow 2002, p. 14-15.

[4] Based on the testimony Józef Woch, a resident of Trzebionka given on June 27, 1945, to the Main Commission for Investigation of German Crimes, renamed later the Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes. APMAB. Proces Załogi ZO Vol. 62, p. 37.

[5] A detailed description of this type of crematorium is located in the section on the sub camp Blechhammer.

[6] Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Trzebinia [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 188.

[7] Testimony of Józef Woch 27 June 1945. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content.

[8] Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Trzebinia [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1975] Nr 16, p. 188.

[9] Testimony of Michał Stefański 28 June 1954. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content.

Literature:

Piper, Franciszek, Das Nebenlager Trzebinia, [in:] Hefte Von Auschwitz [1978] Nr 16, p. 93-135.

The Evacuation of the Sub Camp Arbeitslager Trzebinia

In the Trzebinia sub camp in January 1945 there were 641 prisoners.[1] The dissolution of the sub camp in Trzebinia-Trzebionka took place on January 16, 1945. Those prisoners unable to march on foot were taken to the railway siding of the refinery and loaded into four rail trucks, used in the coal mining industry that had temporary roofs made from wooden beams. The train left in an unknown direction. The main column of the prisoners was led out on the evacuation march to the Auschwitz main camp. There however, the evacuation column was not accepted, and the prisoners were sent to the camp in Czechowice. The column arrived there on January 18th and moved further towards Rybnik the next day. The evacuation was recalled by a former prisoner, Benjamin Pilicer: “We remained in Trzebinia until mid-January 1945. The front was approaching, and the Russians were getting closer. One night, food was divided between us. We were given bread and margarine. In addition, we were also given clothes. The night was very cold. We were allowed to take everything with us. At one o’clock in the morning, an order was given, and we went on the march (…). We walked on foot. There was great confusion. We were almost not guarded. It was very easy to escape. People, however, did not run away … they kept to the group. They simply did not know or were afraid to go on their own. The crippled, among us, could barely walk. The Germans themselves began to be fearful. They loaded all their belongings onto carts that we were pushing (…). On the first night, during the march, the Germans were shooting and killing anyone who could not go any further. Later this changed and they did not shoot us anymore. For whoever was weak and could not go on, they remained where they lay (…). We reached Oświęcim (Auschwitz concentration camp) again. Amongst us were all those who could not go any further. All of them were left in Oświęcim (Auschwitz concentration camp). People reported that they could go no further. They were convinced that they were going to their deaths. But exhaustion was so great that they had nothing to lose, because they could not go on (…). We went further. The frost was terrible then. We did not feel the cold though. We were hot with the excess of the effort and exhaustion. We ate snow on the march. My hands were frostbitten, and I suffered very much because of this. People marched and slept. Under the influence of fatigue, we saw things that did not exist. Dragging ourselves along we reached Rybnik in Silesia. 800 people left Trzebinia, and less than half came to Rybnik. At the station in Rybnik, we were loaded into open freight wagons. The snow was falling constantly. It was crowded and snow covered us completely. Under these conditions, we travelled for four days. Frozen, rigid, we arrived at Gross-Rosen (concentration camp). Here, however, they did not want to accept us and were ordered to continue …” [2]

Witnesses living along the route of the evacuation march, as well as one of the guards, SS-man Paul Dost, remembered that those who were unable to march were killed.

Only a few prisoners decided to escape along the evacuation route. Arnošt Tauber, who successfully escaped along with Abraham Piasecki was hidden by one of the inhabitants of Czechowice until the arrival of the Red Army. During the evacuation, the Head Kapo of the camp, Karl Broszio, also escaped.

One of the last events that took place in the sub camp in Trzebinia-Trzebionka was the blowing up of the crematorium.

After the liberation of Trzebinia, documents were found from the sub camp – for example the bonus vouchers for prisoners and business cards left by the SS guards in their lockers. The rest of the camp documentation had been burned by the SS guards. The empty camp was looted by local residents: “After the Germans had left the camp but before the refinery took care of it and set up a guard, the locals plundered the camp premises and all of the camp facilities. Presently, a guard from the refinery watches over the camp.” [3]

[1] Testimony of Otto Wolken 22 June 1945. Viewed 10 August 2019 https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3755/edition/3736/.

[2] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of former prisoner Benjamin Pilicer, Vol. 59, p. 14-77.

[3] Testimony of Józef Woch 27 June 1945. Testimony viewed 8 August 2019. https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3096/edition/3077/content.

Literature:

Piper, Franciszek, Das Nebenlager Trzebinia, [in:] Hefte Von Auschwitz [1978] Nr 16, p. 93-135.

The Post War History of the Former Sub Camp Arbeitslager Trzebinia

After the war the former sub camp area was taken over by the state owned Rafineria Nafty Trzebinia, “Barrack from the time of sub-camp activity; after war adapted for common room of refinery; 1965.” (photograph reference 22247).

The Preservation Status of Former Sub Camp Arbeitslager Trzebinia

The sub camp Trzebinia was located near the refinery Trzebinia in the village of Trzebionka (currently a district of the city of Trzebinia). The eastern camp fence stretched along ul Kruczkowskiego, while the southern fence ran along ul Końcowa. On this street there was the main entrance to the camp, above which was the inscription “ARBEITSLAGER TRZEBINIA”.

No remnants of the sub camp Trzebinia exist today.

A few buildings remain connected to the Trzebinia sub camp and located directly at the refinery. The main administrative and management building of Erdöl Rafinerie Trzebinia G.m.b.H. Werk Trzebinia O / S has been preserved. Although the Lagerführer of the sub camp maintained close contact with the management of the refinery, there were matters related to the employment of prisoners, prisoner productivity, etc. that management of the refinery and the commandant of Auschwitz III discussed directly.

In ul Fabryczna there also survives the housing estate for senior civilian employees working at the refinery. Behind these buildings stands a large air raid bunker, used by the engineers and technicians of the refinery.

One of the refinery installations from the war period has been preserved and still exists to this day. It is possible that it was built by the prisoners of the Trzebinia sub camp.

Remnants of the other camps that existed during the Nazi occupation remain both near the oil refinery and at the Trzebinia railway station. These are typical camp barracks now adapted for use by businesses.

Memorialisation

On the other side of ul Kruczkowskiego in 1970 a monument to the victims of Nazism was unveiled in 1970. It takes the form of a small mausoleum with a spire. For reasons unknown, the monument does not contain information about the victims of the Auschwitz sub camp, although beyond doubt it was built to commemorate the prisoners of the Trzebinia sub-camp. [1]

[1] Czubryt – Borkowski, Czesław, Jerzy Michasiewicz, Przewodnik po upamiętnionych miejscach walk i męczeństwa, lata wojny 1939-1945, Warszawa 1980, p. 194.

Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum Site Visit

It seems that the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum had not visited the site of the former sub camp in Trzebinia. There are a number of photographs in the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum archive but these are copies of photographs taken on the inspection visit of the Polish Commission for the Investigation of Nazi War Crimes on 27-28 June and 13 July 1945.

There is a single photograph reference 22247 in the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Archive which was taken in 1965 and is captioned, “Raf Trzebinia 1965 -Stara Swietlica”. It is possible this photograph was taken by somebody else and donated to the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Other Photographs / Site Visits

On 27-28 June and 13 July 1945 a committee from the Polish Commission for the Investigation of Nazi War Crimes visited the former sub camp. The protocol of inspection was conducted on 27-28 June and 13 July 1945 by members of the Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Niemieckich w Polsce (GKBZNwP) [1], Jan Sehn and Edward Pęchalski and Professor Roman Dawidowski.

The camp was substantially intact other than the destroyed crematorium building. The Polish Commission took 11 photographs of the former sub camp, including:

- The remnants of the crematorium (photo references GK_196_145_0026, GK_196_145_0027, GK_196_145_0028, GK_196_145_0029, GK_196_145_0030, GK_196_145_0031, GK_196_145_0032),

- General views of the sub camp (photo references GK_196_145_0016, GK_196_145_0020),

- A wooden guard tower (photo reference GK_196_145_0018),

- The inside of a prisoner accommodation barrack number 4 ((photo reference GK_196_145_0025),

- The exterior of prisoner barrack number 4 (photo reference GK_196_145_0024),

- Sculpture close to the gate (photo reference GK_196_145_0022).

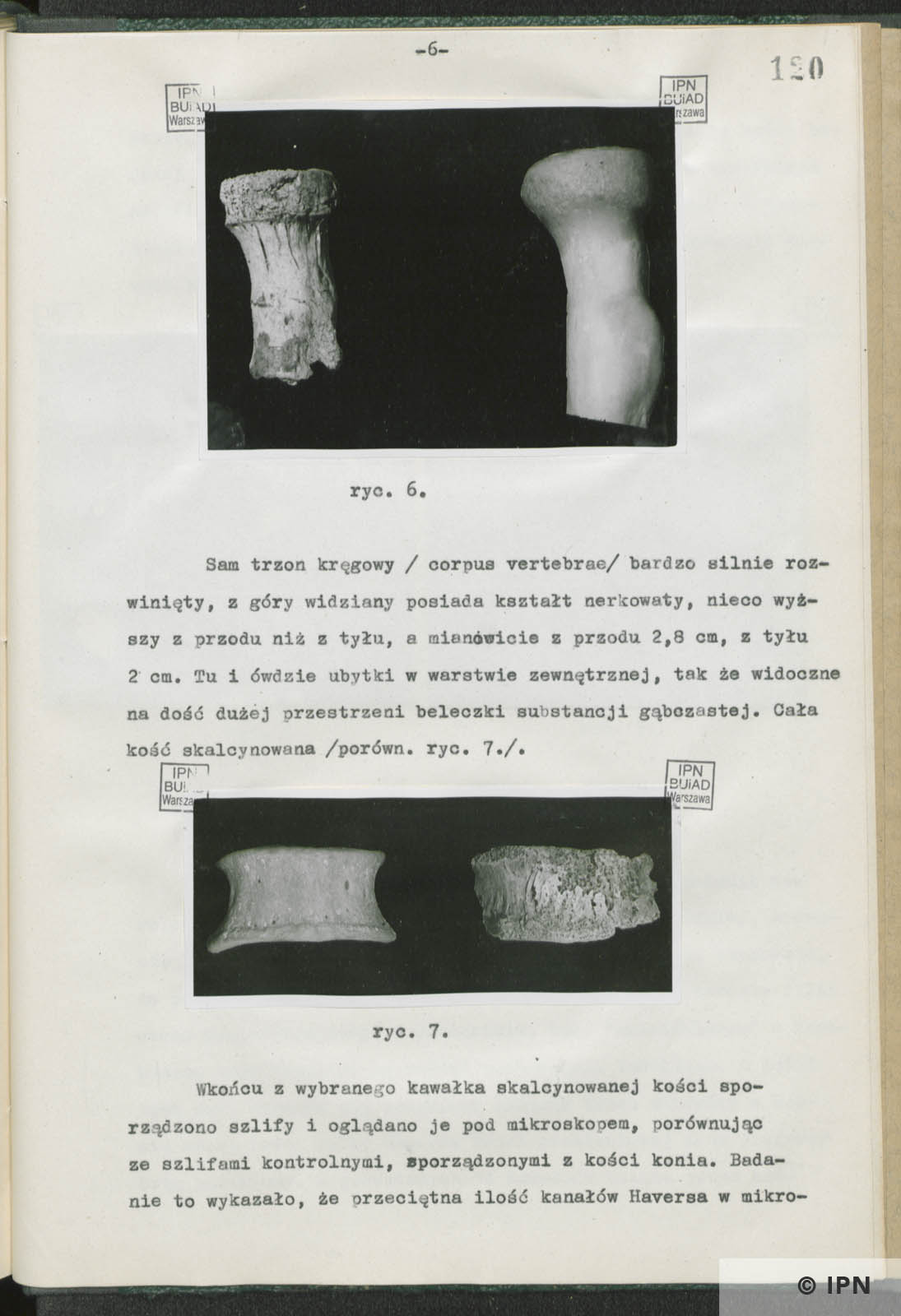

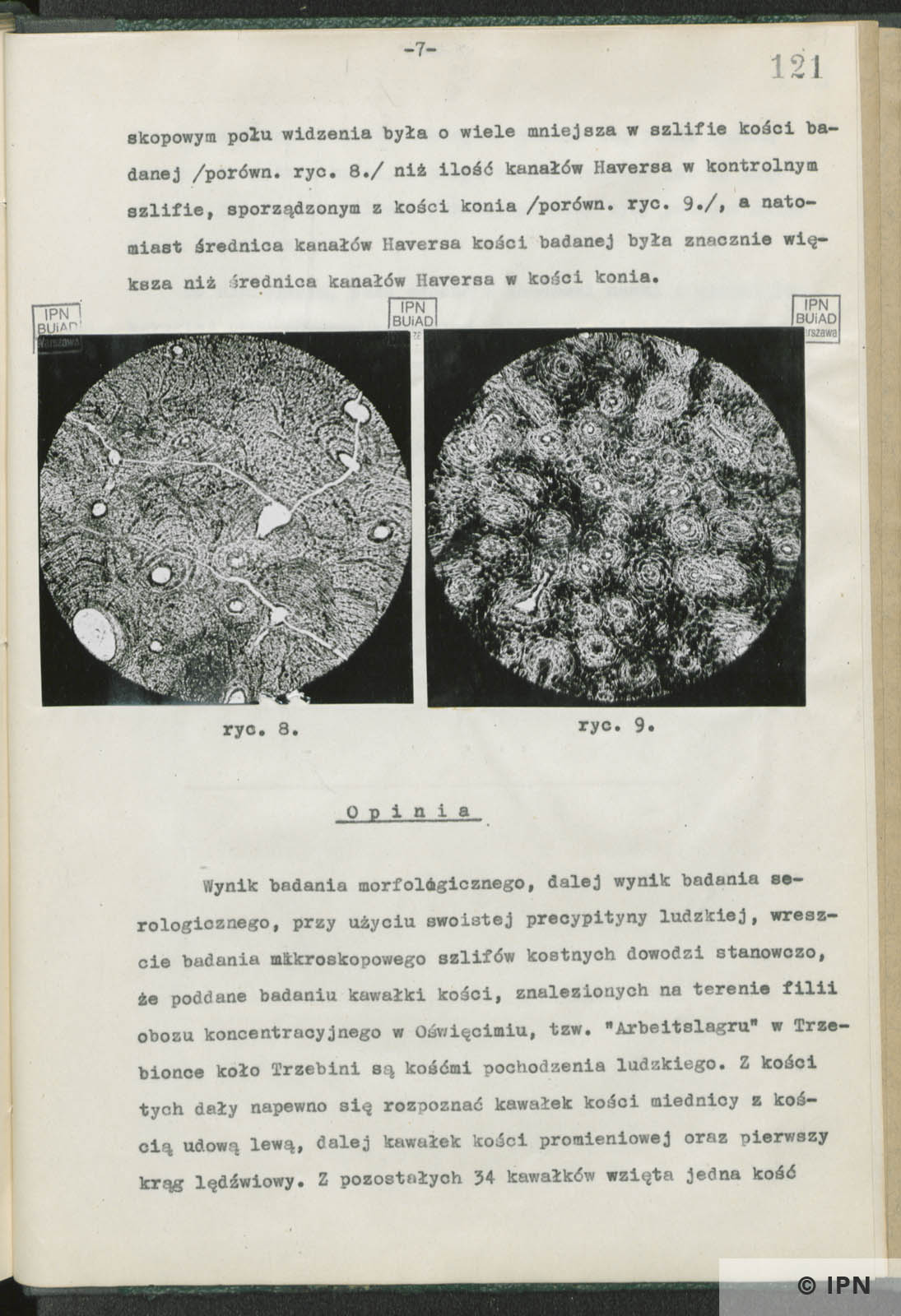

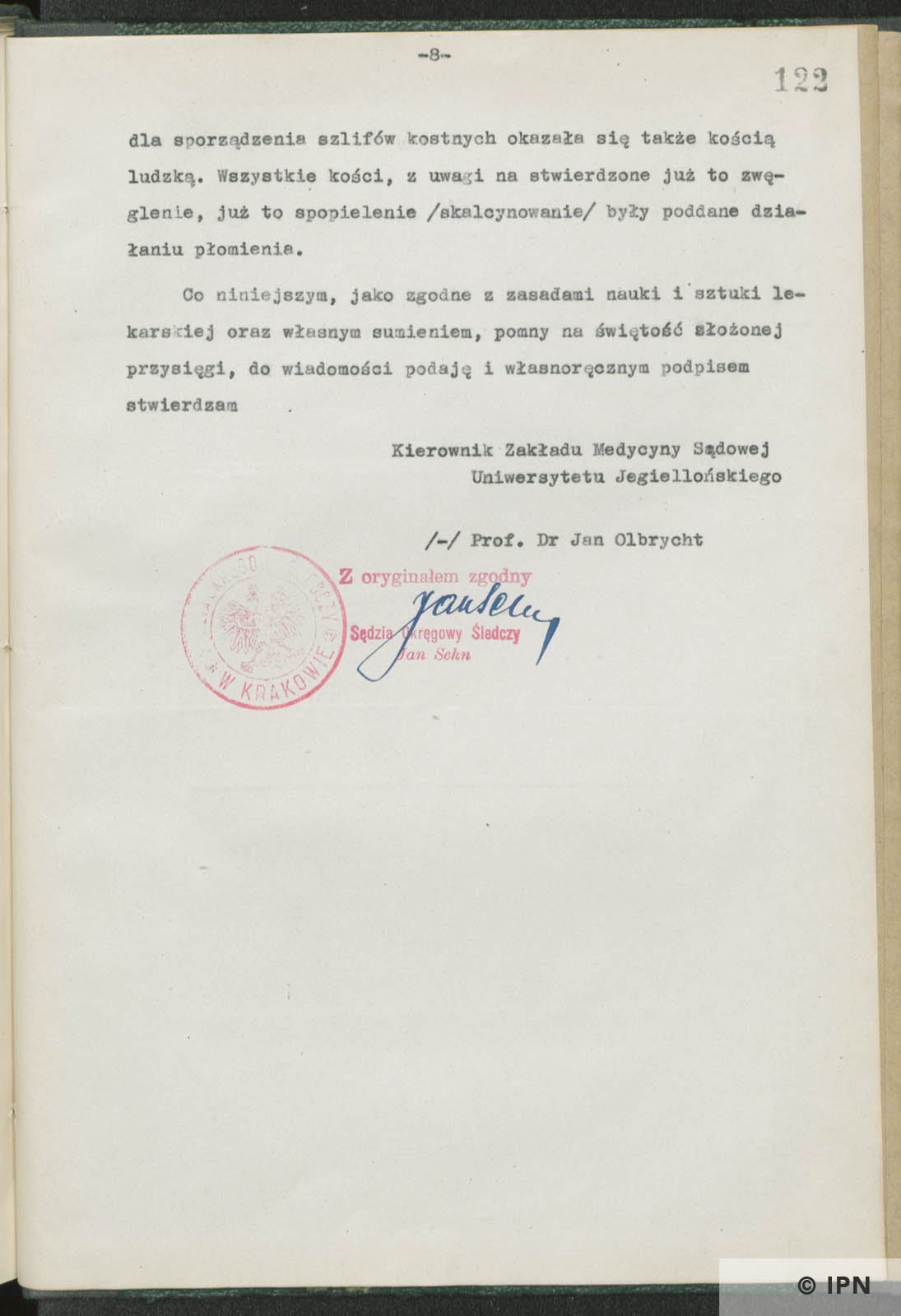

Professor Jan Olbrycht of the University of Jagiellonski produced a report of findings from bone samples taken from the crematorium on the visits of the GKBZNwP. (photo references GK_196_145_118 to GK_196_145_125).

A memorial book on the history of the Trzebinia refinery was published in 1970 and included several photographs taken in 1964 of the refinery. The book is titled Rafineria “Trzebinia” 1895-1970, Krakow 1971.

There are also three photographs from what looks like the unveiling of the monument in 1970.