Bismarckhütte

Commandant of the camp

SS-Oberscharführer Hermann Christoph Klemann

Number of SS Guards

One SS guard and 6 to 7 former Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe men when 80 prisoners. Estimated when maximum number of prisoners as 25 guards.

Work type

Steel Works: Production of cannons and armoured vehicles in the Bismarckhütte steelwork

Employer

Königs- und Bismarckhütte AG part of Berg- und Hüttenwerksgesellschaft Teschen (Berghütte)

Sub camp buildings

Probably built for the sub camp.

Number of prisoners

Between 80 and 200 male prisoners.

On 17 January 1945 192 prisoners.

Nationality of prisoners

Mainly Jews from Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, The Netherlands, Lithuania, Germany, and Poland.

Period of camp existence

September 1944 – 18 January 1945

Dissolution / Evacuation of the sub camp

On 18 January 1945 prisoners were evacuated to Gliwice, then transported to Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp.

Dates of site visits by Tiergartenstrasse4 Association

November 2006 and July 2007

Memorialisation

No known memorial.

Explore more

The History

The history of the companies and the places prisoners worked, the sub camps, the SS guards and memorialisation of the sites.

The History of the Bismarck Steel Works

In 1873 the Kattowizer Aktiengesellschaft für Eisenhüttenbetrieb began operating a steelworks in Hajduki Wielkie.

At the initiative of the first director Wilhelm Kollman, the steel plant was named Bismarckhütte. The plant expanded up to the First World War. In 1906, to Bismarckhütte were added the Falva smelter in Świętochłowice (in German Schwientochlowitz) and iron ore mines near Piekary Rudne and Tarnowskie Góry (in German Tarnowitz). During World War I, Bismarckhütte produced steel for the German war industry. [1]

After the First World War, sections of Upper Silesia in 1922 became part of the newly founded Polish Republic. Bismarckhütte at this time consisted of the Bismarck smelting works in Hajduki Wielkie and the Bethlen-Falva smelting works in Świętochłowice.[2] In 1933 the steelworks changed its name to Huta Batory.[3]

Just before the outbreak of the Second World War there were four industrial conglomerates in Poland including Wspólnota Interesów dla Katowickiej S.A. i Zjednoczonych Hut Królewska i Laura which owned: Huta Piłsudski (formerly Huta Królewska), Huta Laura, Huta Zgoda, Mechanical Workshops at the Huta Królewska. Factories manufacturing Fitzner screws and rivets in Siemianowice, Huty Bismarck, Huta Falva, Huta Silesia and Huta Hubertus. [4]

The steel plant occupied a large area of the Huta Batory district, also known as the Grand Hajduki. After the outbreak of World War II, the steel plant passed into the hands of the German receivers. Its name was changed back to Bismarckhütte and it was incorporated into the Interessengemeinschaft für Bergbau und Eisenhüttenbetrieb.

At the end of 1939 and 1940, the Germans carried out extensive deportations from the Hajduki area, and many Poles were deported to forced labour in Germany. At the same time German Silesians were conscripted into the Wehrmacht, including steelworkers employed in the production of armaments. These decisions made it imperative to replace the lost workers in the steel mill with forced laborers [5].

As replacement workers Polish, French, Soviet, Ukrainian, Czech and Belgian forced labourers were brought to the steel works. Soviet, French and British POWs were also brought to Hajduki. After the capitulation of Italy in the Autumn of 1943 Italian military internees arrived.[6]

In Grand Hajduki, in the immediate vicinity of the steelworks Bismarckhütte numerous forced labour camps were established including:

- A forced labour camp for Soviet POWs, a subsidiary of the work camp in Cieszyn (Kommando R 73 Stalag VIII B), where in August 1942 there were 99 prisoners, and by January 1945 474 prisoners. [7]

- A subsidiary camp of the British POW labour camp in Cieszyn (Kommando E725 Stalag VIII B), in which by January 1945 there were 268 prisoners. Stalag Luft VIII B Lamsdorf was later renamed Stalag 344 and controlled over 700 outside Working Parties of British prisoners of war. [8]

- A labour camp established in 1943, and closed in January 1945, which was located on the so called Kochłowice highway. In 10 barracks lived on average 2,140 people (140 Poles, 100 French, 100 Ukrainians, and 1800 Italians). During the dissolution of the camp, the prisoners were deported to Germany, some were liberated.[9]

In addition, to the camps described above, there were five other subsidiary camps of Soviet prisoners of war in the Chorzów area, from the camp in Cieszyn i.e. Kommando R 88 Stalag VIII B (790 prisoners), Kommando R 143 Stalag VIII B (210 prisoners), Kommando R 172 Stalag VIII B (675 prisoners), Kommando R 193 Stalag VIII B (663 prisoners), Kommando R Stalag VIII B 798 (80 prisoners). There were also two additional subsidiary camps of British prisoners of war from the camp in Cieszyn i.e. Kommando E 594 Stalag VIII B (197 prisoners) and Kommando E 746 Stalag VIII B (601 prisoners). There were also the following labour camps: 1) In Maciejkowskiej Street in Chorzów at a factory making nitrogen compounds, Ukrainians (about 100), 2) A work camp in Nowa Street in Chorzów, the home of French, Poles and Ukrainians working in steel mills, and 3) A Judenlager labour camp, which was housed in barracks built at the tram depot at the mine, Cleophas.[10]

The senior management of the Bismarck Steel Works were Germans, transferred to Chorzów from Altreich. The Reichstreuhänder (chairman) was a man named Pietsch and the technical director a man named Kallenborn. Kallenborn was there a relatively short time, and he left on 19 October 1940.

The removal of the technical director Kallenborn was sudden and unexpected. This happened as a result of serious abuses during the valuation of the steel mills of Silesia Rybnik. Kallenborn bribed one of the industrialists to deliberately lower the value of the steel mills in the bidding process for several of the limited liability companies. However, the Kattowitz Gestapo found out about this, and despite numerous interventions on his behalf lauding his contributions to the struggle for Poland Kallenborn he was forced to leave Silesia. [11]

In 1942, after the reorganization of the steel mill Bismarckhütte, it became part of the Berghütte group (Berg- und Hüttenwerksgesellschaft Teschen) and the company Königs-und Bismarckhütte Aktiengesellschaft – Königshütte Ost. The company Königs-und Bismarckhütte Aktiengesellschaft – Königshütte Ost owned the following companies: Bankhütte (Steelworks Bank), Bismarckhütte (Steelworks Batory), Falvahütte (Steelworks Florian), Hubertushütte (Steelworks Zygmunt), Katharinahütte (Steelworks Buczka M.), Königshütte (Steelworks Kosciuszko), Laurahütte (Steelworks Unity), Milowitzhütte (Steelworks Milowice) and Silesiahütte (Steelworks Silesia).

[1] Widuch, B, i inni, Huta Batory, Chorzów 1993.

[2] Jarosz-Nojszewska, Anna, Smelting Industry in the Second Republic: http://kolegia.sgh.waw.pl/pl/KES/czasopisma/kwartalnik/Documents/AJN30.pdf. Viewed 15 August 2019.

[3] Kurek, Jacek, Historia Wielkich Hajduk, Chorzów-Batory – Wielkie Hajduki 2001, p. 56.

[4] Jarosz-Nojszewska, Anna, Smelting Industry in the Second Republic: http://kolegia.sgh.waw.pl/pl/KES/czasopisma/kwartalnik/Documents/AJN30.pdf. Viewed 15 August 2019.

[5] Loch, Alojzy, Szendzielorz, Gerard, Kartki z dziejów Huty Batory, Stalinogród (Katowice) 1956, p. 159-160.

[6] Strzelecka, Irena, Podobóz Bismarckhütte, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p.148.

[7] Obozy hitlerowskie na ziemiach polskich 1939-1945. Informator encyklopedyczny, Warszawa 1979, p. 133-134.

[8] Obozy hitlerowskie na ziemiach polskich 1939-1945. Informator encyklopedyczny, Warszawa 1979, p. 133-134.

[9] Obozy hitlerowskie na ziemiach polskich 1939-1945. Informator encyklopedyczny, Warszawa 1979, p. 133-134.

[10] Obozy hitlerowskie na ziemiach polskich 1939-1945. Informator encyklopedyczny, Warszawa 1979, p. 133-134.

[11] Loch, Alojzy, Szendzielorz, Gerard, Kartki z dziejów Huty Batory, Stalinogród (Katowice) 1956, p. 160.

The Post War History of the Bata (Formerly Bismarck) Steel Works

After the end of World War II, the Bismarck Steel Works renamed Batory Steel Works was nationalised. In the 1950s, modernization of the steel plant began, including the steel mills and overhaul of the rolling mills. [1]

After 1992 the Batory Steel Works was transformed into a joint-stock company. The enterprise restructuring at that time resulted in the division of the steelworks into a number of independent companies. As part of the Batory smelter, only the steelworks and pipe mill departments remained.

In 2005, individual parts of the divided steelworks were bought by Alchemia S.A. [2]

[1] Rut, Tadeusz, Ulepszona metoda TR kucia wałów korbowych… “Plastyczna obróbka metali”, p. 13–21, 1998. Poznań.

[2] http://alchemiasa.pl/grupa-kapitalowa/historia-firmy. Viewed 19 August 2019.

The History of the Sub Camp Bismarckhütte

The sub camp of Auschwitz in Chorzów had been planned to open in mid 1943. This date has been derived from the analysis of the materials of the Auschwitz Camp Resistance Movement by Irena Strzelecka of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.[1] The sub camp of Bismarckhütte actually only opened a year later in September 1944.

The earliest preserved evidence of the existence of this sub camp comes from a document dated 18th November 1944 an order for road transport (Kraftfahrzeug Anforderung) for the movement of prisoner’s clothes from the storage depot in Auschwitz to the sub camps Bismarckhütte, Sosnowitz II and Laurahütte. [2]

Former prisoner, Raimund Schwerberger, “If I remember correctly it was around October 1944 that I came to NL Bismarckhütte. The NL Bismarckhütte was being set up. We were at first approximately 60 prisoners, the total strength of NL Bismarckhütte was never more than 60 prisoners. I was responsible for the camp kitchen but first had to get involved with construction work in the camp as there was only a shell there. Part of the time we also worked in the Hüttenwerk Bismarckhütte unloading boxcars. In the Hüttenwerk itself we did not work.”[3]

The sub camp of Bismarckhütte was established on the outskirts of Chorzów-Batory close to the road leading to Kochłowice. Irena Strzelecka from interviews with residents of Chorzów ascertained that the camp area was approximately 200 m long and approximately 80-100 m wide. The whole area was surrounded by a double row of barbed wire hung on concrete posts and the inner fence was probably electrified. At the four corners were built guard towers. The main entrance to the camp was near ul Kochłowicka. At night the camp was lit up by floodlights installed on the guard towers and fence posts around the camp. In addition, to the guards on the guard towers, SS guards and dogs patrolled day and night around the camp. The camp was located on a busy road in the heart of Upper Silesia and so to prevent unauthorized viewing of the sub camp in November or December 1944 a high fence was erected made of metal or cement panels. Inside the fenced area there were several barracks made from wooden or cement panels. In one of them there was a camp kitchen and canteen for the SS. In a small wooden barrack standing near the entrance gate of the camp, the camp commandant was located and there was also an office. The barracks, in which the prisoners lived were made of wooden panels. The SS and former Wehrmacht soldiers, who guarded the prisoners lived in a wooden barrack standing outside the camp fence. [4]

There was also a small prisoner hospital with a capacity of 5 to 6 beds. [5]

In the sub camp Bismarckhütte there were about 200 prisoners (or as few as 80 [6]) confirmed from surviving materials of the Auschwitz Camp Resistance.[7] They were mainly Jews from Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, The Netherlands, Lithuania, Germany, and Poland. There were also four to five German prisoners and a few Poles. [8]

In the first stage of the existence of the sub camp, prisoners were employed primarily in construction work associated with the development and expansion of the sub camp. They erected barracks, cleaned up the area etc.

The prisoners were dressed in standard prisoner clothing: “(…) on their heads they had a round cap made of the same striped fabric as their blouse and trousers, and they wore wooden clogs on their feet. Their trousers were too short, you could see their bare legs. Everyone looked very bad, they were so called Muslims.” [10]

Probably in November 1944 the prisoners began working in the Bismarckhütte steelworks. Prisoners employed in the mill left the sub camp in groups of 60-80. They were escorted by SS men with dogs who were at the front and rear of the columns. The prisoners walked five abreast in the direction of ul Żelazna and through gate No. V into the steelworks. [11]

Most of the prisoners were employed in the work halls of the production department which made parts for anti-aircraft guns, armour plating, etc. During working hours, they were guarded by the SS, Kapos and factory guards. [12] Jerzy, Dziadzia, a civilian worker at the Bismarck steel works, working in the production department in November 1944, “ After a couple of days SS men brought 40 prisoners dressed in prisoner clothing to our department. On their feet they wore wooden shoes, their shaven heads were covered with a round hat made of the same material as their trousers and jackets. They were marked with red, green and black badges. In addition the Jews had a star on their sleeve. They were between 25 and 60 years old. Apart from the functionary Kapos they looked bad. They were placed in the five hangars of the mechanical department. They had obviously been trained in a profession, because they were able to do their jobs at the machines (for example lathes, planing machines, milling machines). Prisoners also worked in other departments. Later I learned that the prisoners in the sub camp Bismarckhütte came from the concentration camp Auschwitz. I was assigned three prisoners, a German, a Hungarian and a Romanian. They worked from 6.00 hrs. to 18.00 hrs with a lunch break at 15.00 hrs. In one of the work halls a cauldron of soup was brought together with tin bowls. At the whistle of the Kapo, the prisoners lined up in rows, ran to the caldron and the Kapo poured for each one a ladle of soup into the tin bowl. The civilian workers were forbidden to approach the prisoners; I don’t know what was in the soup. During the lunch break the functionary Kapos had beaten the prisoners when they didn´t run to pick up their portion. The prisoners were very hungry. Other than lunch, in the area of the steel works the prisoners did not receive any food. Some of the civilian workers had helped the prisoners by leaving in specific places bread, cigarettes and other things. When a Kapo noticed that a prisoner had something, he searched him and ordered him to open his mouth and beat him when he found he had bread or sausage. In the work halls SS men guarded the prisoners. Outside of the work halls the SS men had Alsatian dogs. I witnessed a prisoner being brutally beaten and kicked because he had picked up a cigarette stub. It didn’t happen that a prisoner was murdered on the area of the production department. One time a breakfast for civilians went missing which was reported to the SS or Kapos. They immediately ordered all the prisoners to be collected. The Kapos as well as the SS men beat the prisoners for approximately 30 minutes with bull whips. One of the prisoners owned up to taking the breakfast. I don’t know whether he was the perpetrator of the theft of the breakfast or just wanted to end the torture of the prisoners. The next day the prisoner did not appear at work. From one of the prisoners assigned to me I learned that the prisoner who had owned up to stealing the breakfast had been murdered in the sub camp.” [13]

In 1948 on the site of the former Bismarckhütte area a mass grave for eleven prisoners was found. Seven of the dead prisoners were found to be Soviet Prisoners of War and four were Poles. [14]

[1] Strzelecka, Irena, Podobóz Bismarckhütte, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p.149.

[2] APMAB. Kraftfahrzeung Anforderung from 18 November 1944.

[3] Sta Ludwigsburg StAL EL 48-2-BA 2424, p. 6.

[4] Strzelecka, Irena, Podobóz Bismarckhütte, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p.152-154.

[5] Strzelecka, Irena, Das Nebenlager Bismarckhütte, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz [1970] Nr 12, p.154.

[6] Sta Ludwigsburg StAL EL 48-2-BA 2424, p. 6.

[7] APMAB. Materiały Ruchu Oporu, Vol. III, p. 208-212.

[8] Sta Ludwigsburg StAL EL 48-2-BA 2424, p. 6.

[10] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of witness Alojzy Giemza, Vol. 52, p. 182.

[11] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of witness Alojzy Giemza, Vol. 52, p. 182.

[12] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of witness Alojzy Giemza, Vol. 52, p. 182.

[13] B162/9669, p.152-155. Testimony of Jerzy Dziadzia.

[14] B162/9669, p. 148-149 Testimony of Dziamski, Boleslaw.

Literature:

Strzelecka, Irena, Das Nebenlager Bismarckhütte, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz [1970] Nr 12, p. 145-159.

Strzelecka, Irena, Podobóz Bismarckhütte, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 145-158.

The SS Guard Unit

The Lagerführer of the sub camp was SS-Oberscharführer Hermann Christoph Klemann, born 26 September 1915 in Westdorf [1] and the paramedic was SS-Oberscharführer Franz Wloka. [2] The only SS guard was the Lagerführer, Klemann, the other guards were 6 to 7 were former Luftwaffe men. [3]

The Lagerältester was Bruno Brodniewicz, prisoner number 1 who had performed the same function in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Zigeunerlager and the Auschwitz sub camps of Neu-Dachs and Eintrachthütte. [4]

[1] Sta Ludwigsburg StAL EL 48-2-BA 2424.

[2] APMAB. SS-Hygiene Institut, segr. 13/283.

[3] Sta Ludwigsburg StAL EL 48-2-BA 2424. p. 6.

[4] Rudorff, Andrea, Bismarckhütte in Des Ort des Terrors Band 5, Geschichte der Nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. C.H.Beck 2007, p 185.

Literature:

Strzelecka, Irena, Das Nebenlager Bismarckhütte, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz [1970] Nr 12, p. 145-159.

Strzelecka, Irena, Podobóz Bismarckhütte, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 145-158.

The SS Guards

References:

Zppw-auschwitz.pl Zwiazek Polaków Pomordowanych w Auschwitz. List of 8,500 SS men in KL Auschwitz.

BA Ludwigsburg B162/2680 and B162/2679.

IPN database of Auschwitz SS guards. https://truthaboutcamps.eu/th/form/60,Zaloga-SS-KL-Auschwitz.html

Strzelecka, Irena, Das Nebenlager Bismarckhütte, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz [1970] Nr 12, p. 145-159.

Strzelecka, Irena, Podobóz Bismarckhütte, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 145-158.

Evacuation of the Sub Camp Bismarckhütte

On 17th January 1945 in the sub camp Bismarckhütte the prisoners numbered 192.[1] The evacuation of the sub camp took place on January 18, 1945 nine days before the Red Army entered the city of Chorzów. The prisoners were ordered into a column, then marched out of the gate of the sub camp escorted by the guards. Irena Strzelecka ascertained that the leader of the evacuation coulmn was SS-Oberscharführer Klemann. The prisoners were despatched on the death march dressed only in their striped uniforms, in wooden shoes (some walked barefoot), dragging sledges loaded with material. [2]

During the march to Gliwice according to former prisoner Raimund Schwerberger, “On this march the leader, a Luftwaffe sergeant shot 6 prisoners that could no longer walk with a neck shot and buried them next to the street.” [3]

Two days later, the column arrived in Gliwice, where the prisoners from Bismarckhütte mixed together with prisoners from other sub camps, were loaded onto railway trucks, and transported to the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp near Nordhausen from where they were transported to Niedersachswerfen. The surviving prisoners were liberated by American troops in May 1945 during the evacuation from Dora-Mittelbau to Hagenow. [4]

[1] Testimony of Otto Wolken 22 June 1945. Viewed 10 August 2019 https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3755/edition/3736/

[2] Strzelecka, Irena, Das Nebenlager Bismarckhütte, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz [1971] Nr 12, p. 158-159.

[3] Sta Ludwigsburg StAL EL 48-2-BA 2424, p. 8. Testimony of Raimund Schwerberger.

[4] Strzelecka, Irena, Das Nebenlager Bismarckhütte, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz [1971] Nr 12, p.158-159.

Literature:

Strzelecka, Irena, Das Nebenlager Bismarckhütte, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz [1971] Nr 12, p. 145-159.

The Post War History of the Former Sub Camp Bismarckhütte

In 1946, a German prisoner of war camp was established in the former Bismarckhütte sub camp at the Batory smelter. It was named the Centralny Obóz Pracy w Jaworznie (Jaworzno COP branch camp), while the management of the smelter where the prisoners worked came under the authority of the CZPH (Central Commitee for Metallurgical Industry).

The prisoners were accommodated not only in the barracks of the former Auschwitz sub camp, but also in the barracks of the former labour camps for Soviet and British prisoners of war. According to data from April 20, 1948, 124 prisoners of war were housed in the camp, who worked at the Batory smelter in Chorzów. The camp was dissolved in 1949.[1]

By the time of the site visit by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum on 17th February 1967 little remained of the sub camp. The construction of a housing estate directly on the site was begun in the early 1960s.

[1] Kopka, Bogusław, Obozy pracy w Polsce 1944-1950. Przewodnik encyklopedyczny, Warszawa 2002, p. 84.

The Preservation Status of the Former Sub Camp Bismarckhütte

Bismarckhütte is one of the few sub camp of Auschwitz visited by Tiergartenstrasse4Association between 2005 and 2008 where there were no remnants (not even a solitary drain) of the sub camp. The sub camp was located on the outskirts of Chorzów-Batory on the right hand side of the road leading to Kochłowice. Today this area is bordered by ul Czempiela from the north, ul Stefana Batorego to the east and the railway line to the south.

This was quite a large camp of about 200 meters length and a width of approximately 80-100 meters made up of three prisoner barracks and a barrack for the camp guards. The camp was surrounded by a double row of barbed wire fencing, the inner fence probably electrified and watchtowers. [1]

Tiergartenstrasse4Association undertook two research trips to Bismarckhütte between 2005 and 2008 to find remains of the camp. Unfortunately, these field visits have confirmed that there are no remaining camp remnants. Undoubtedly, this is related to the construction of a housing estate directly on the site, begun in the early 1960s. Most likely during the further construction of the housing estate the few remnants seen by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in 1967 were dismantled.

At the time of our visits the steelwork Batory in Chorzów, in which the prisoners worked still existed.

[1] Strzelecka, Irena, Podobóz Bismarckhütte, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 152.

Memorialisation

At the time Tiergartenstrasse4Association visited the site of the former sub camp there was no on-site memorial or information in the form of a bulletin board, that indicated the existence of the sub camp of Bismarckhütte.

Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum Site Visits

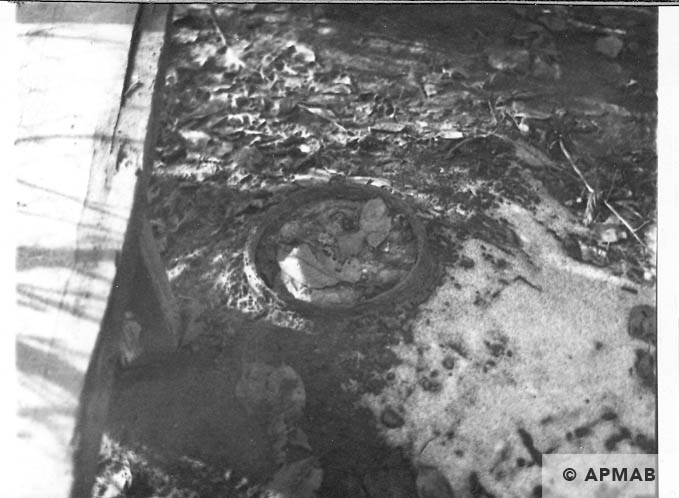

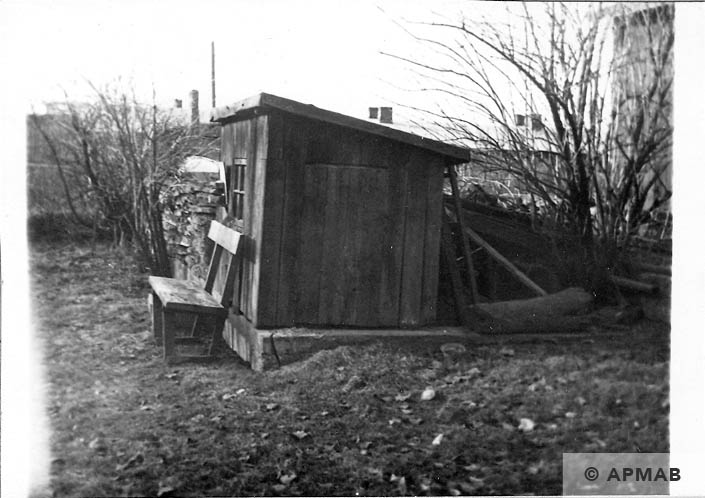

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum visited the site of the former sub camp of Bismarckhütte on 17th February 1967 and took three photographs:

- “Brick barrack which was used as the kitchen and canteen for SS-men; 1967.” (photo reference 10626),

- “Fragment of brick barrack which was used as the kitchen and canteen for SS-men in 1967.” (photo reference 10627),

- “Building built from materials of old barracks; 1967.” (photo reference 10628).

At that time of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum site visit, to the former sub camp Bismarckhütte there remained only a stone barrack, which housed the kitchen and canteen for the SS, and fragments of the foundations of prisoner barracks and a metal fragment of one of the four pillars, which were used to support the guard towers. Undoubtedly, the lack of remaining infrastructure of the former sub camp was related to the construction of a housing estate directly on the site, begun in the early 1960s.