Neu-Dachs

Other Name of the camp

Aussenlager Jaworzno

Arbeitslager EVO Jaworzno

SS-Lager Dachsgrube

SS-Lager Dachs

Barackenlager Dachsgrube

Zweiglager Neu-Dachs

SS-Arbeitserziehungslager Jaworzno

Commandant of the camp

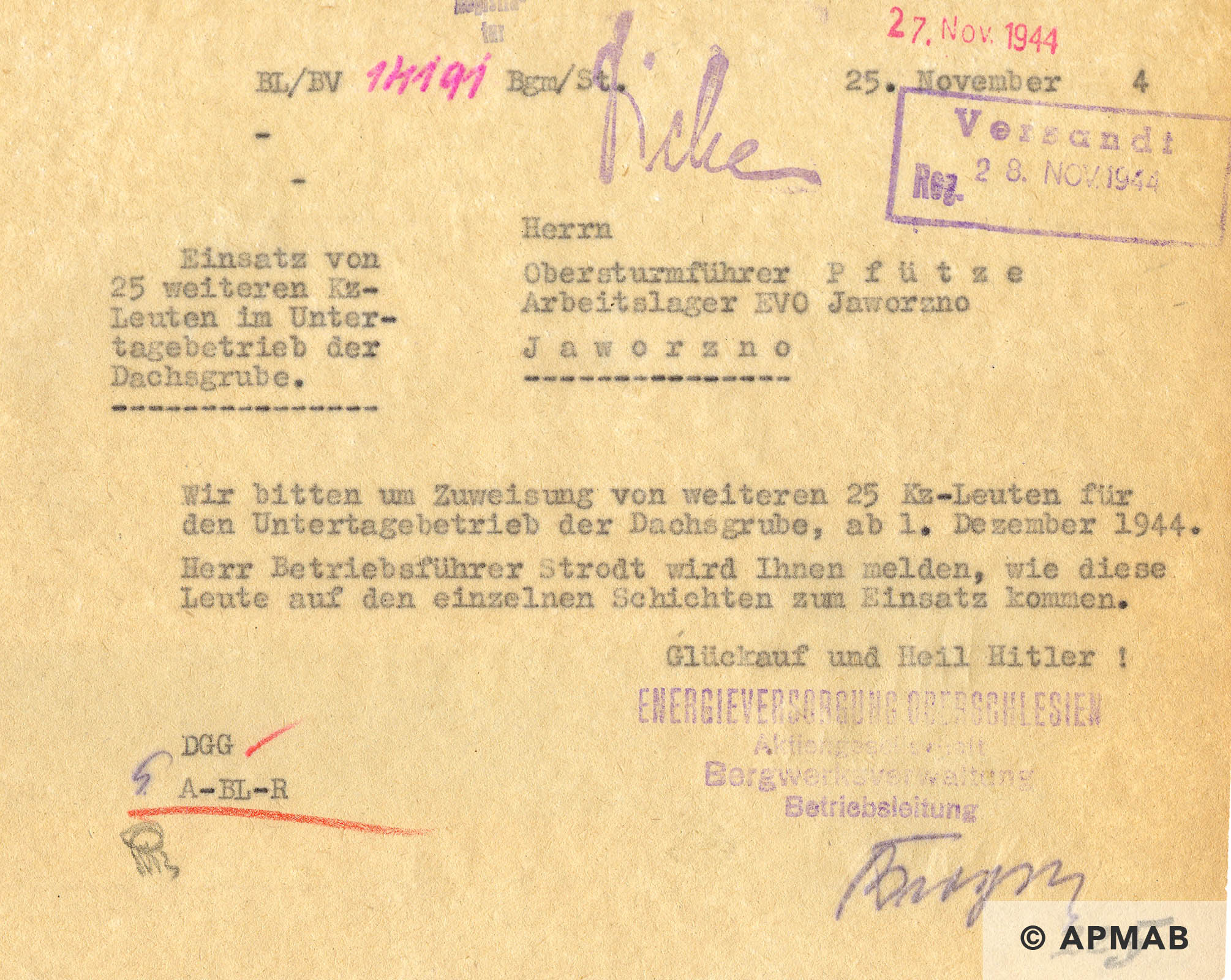

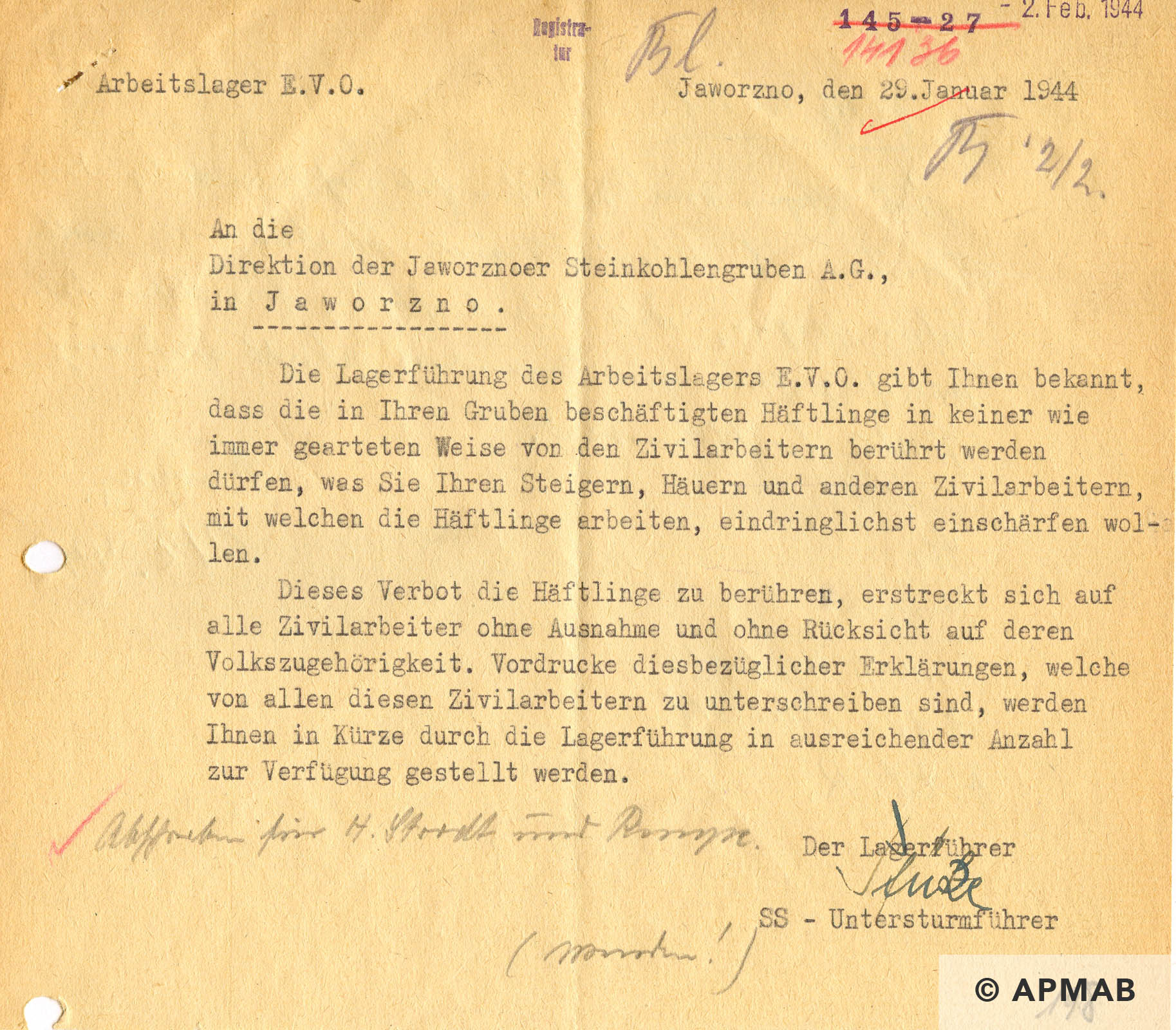

SS-Obersturmführer Bruno Pfütze: 15 June 1943 – 17 January 1945

Number of SS Guards

Estimated 200 SS guards.

Work type

Coal Mining: Coal mining in the Jaworzno mines of Dachsgrube, Rudolfgrube and Richardgrube, construction of the Kraftwerk Wilhelm and expansion of the Kraftwerk Friedrich-August power plants.

Employer

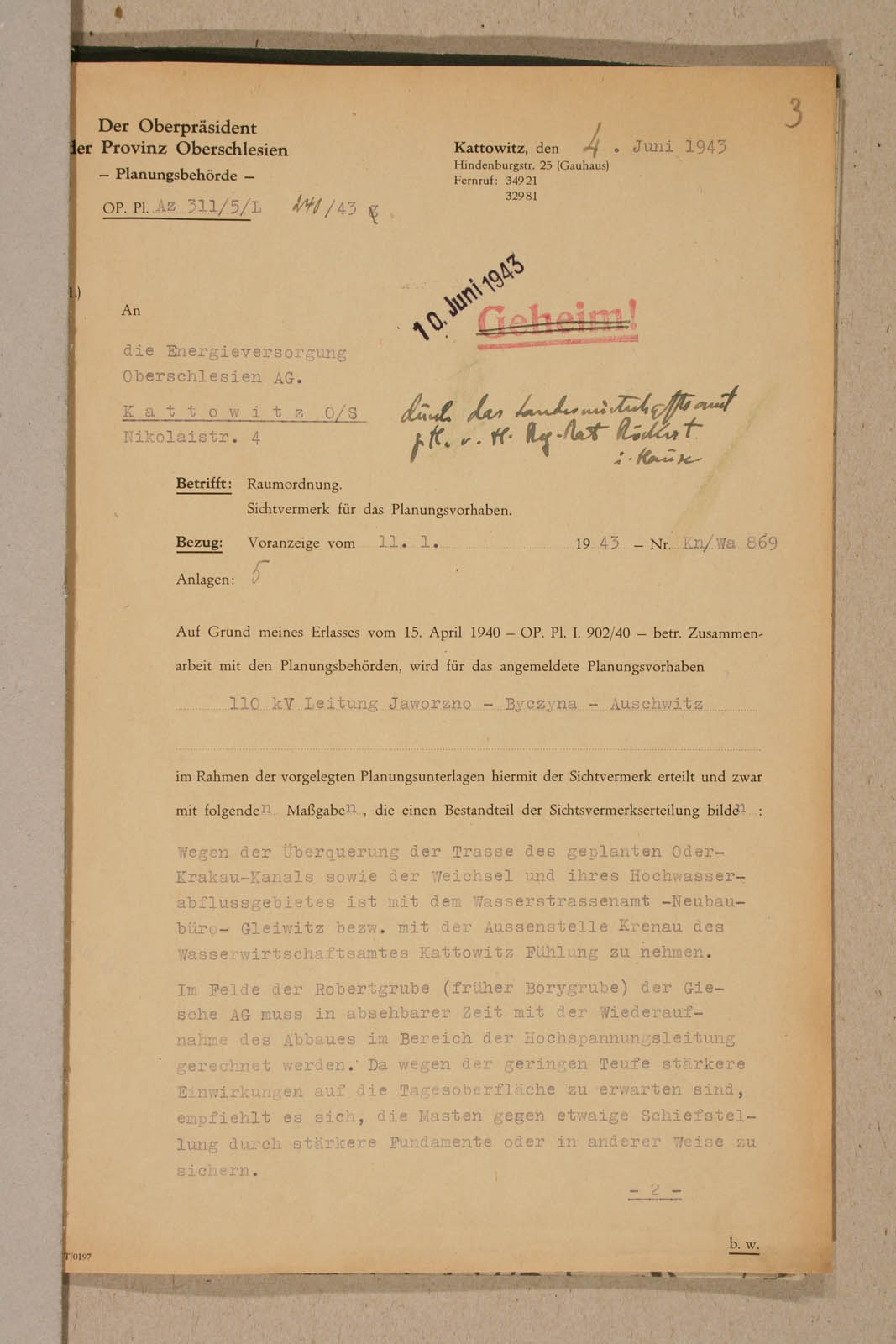

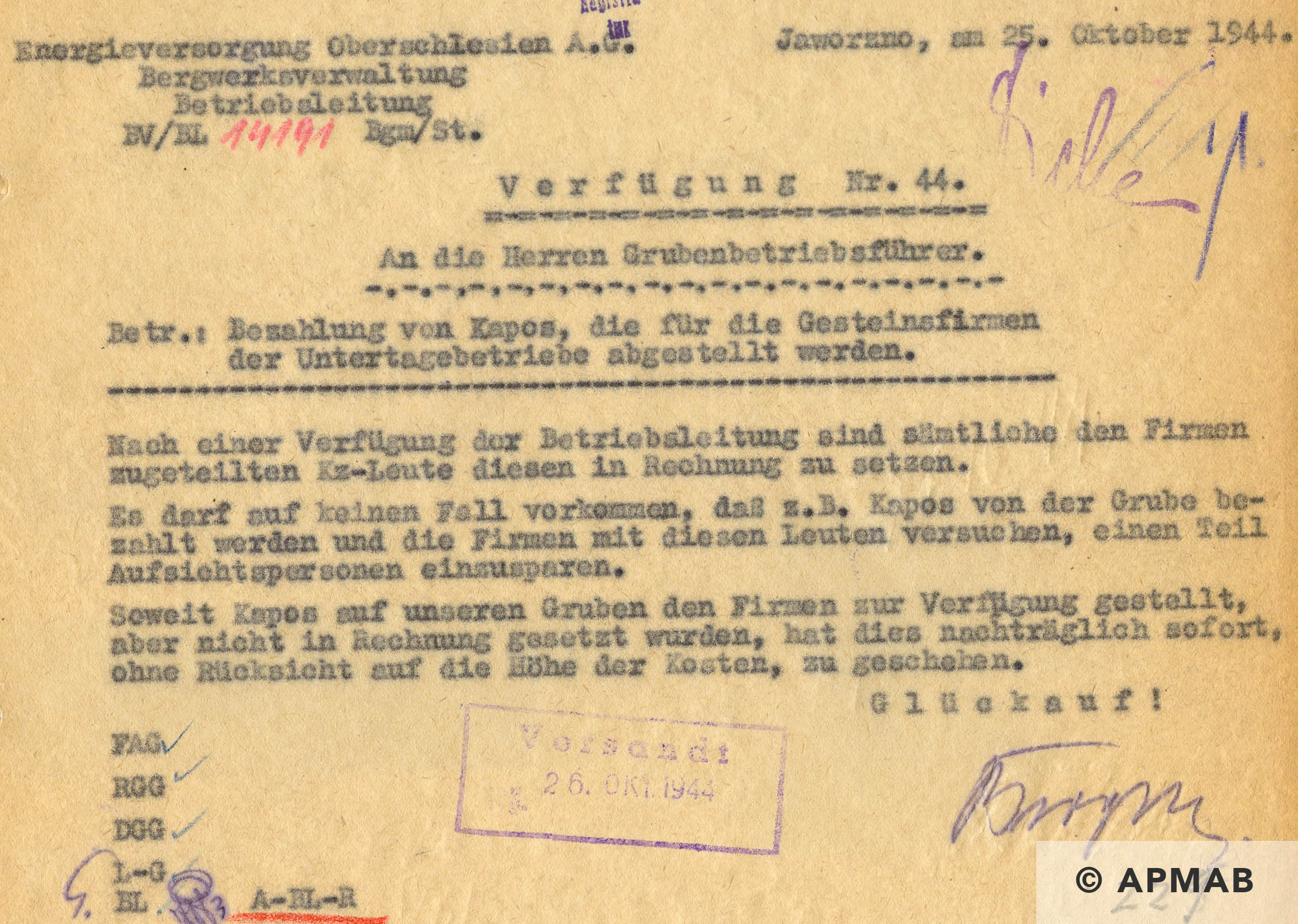

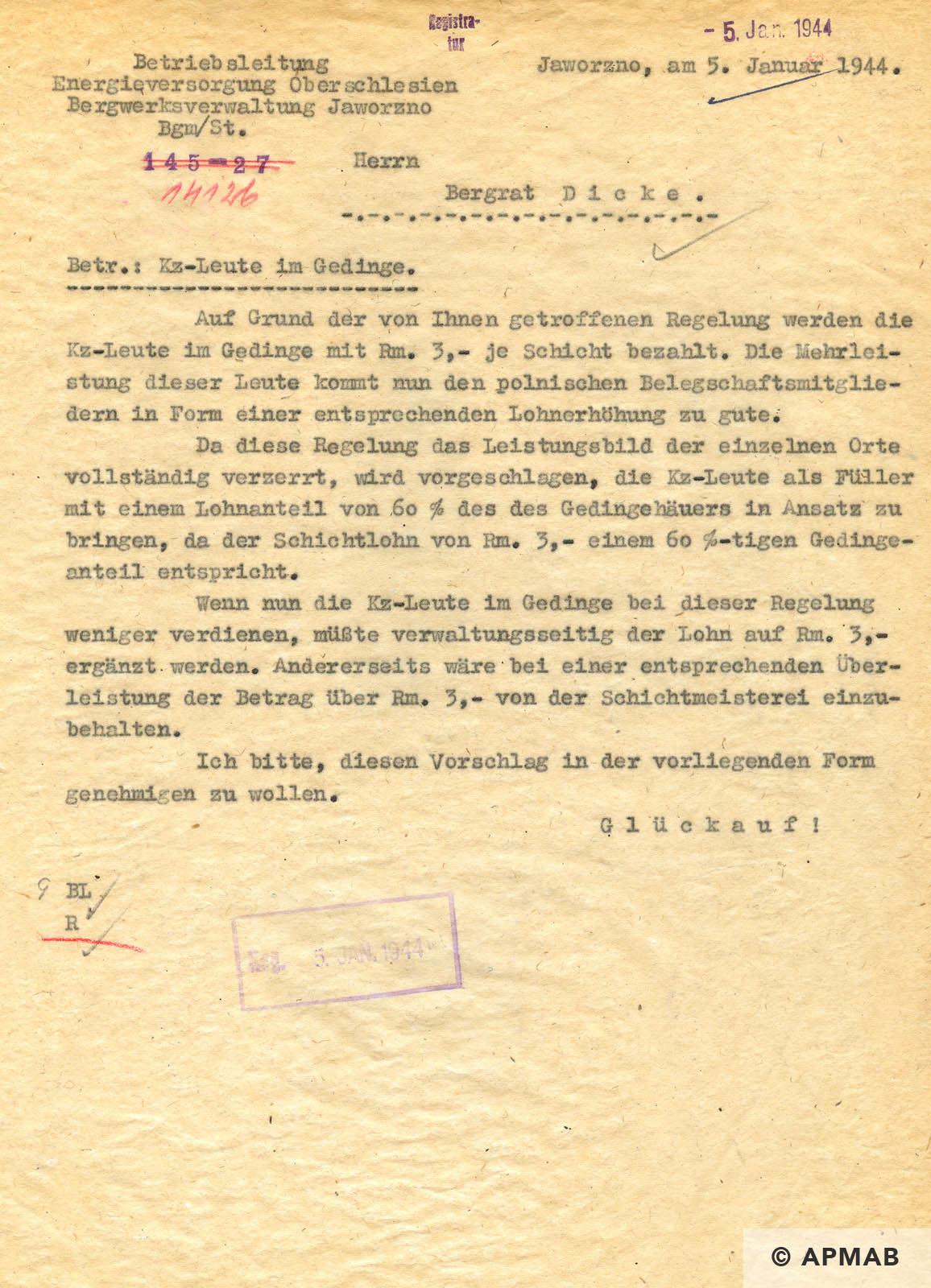

Energie-Versorgung Oberschlesien AG (EVO) a state owned entity.

Sub camp buildings

In June 1943 upon arrival of the first Auschwitz prisoners there existed only a wooden barrack used as a camp kitchen and wooden barracks for the SS. The Auschwitz prisoners expanded the camp.

Number of prisoners

Male prisoners:

June 15 1943: 100

August 1943: 1600

January 1944: around 2000

Summer 1944: around 3200

January 17 1945: 3664

Nationality of prisoners

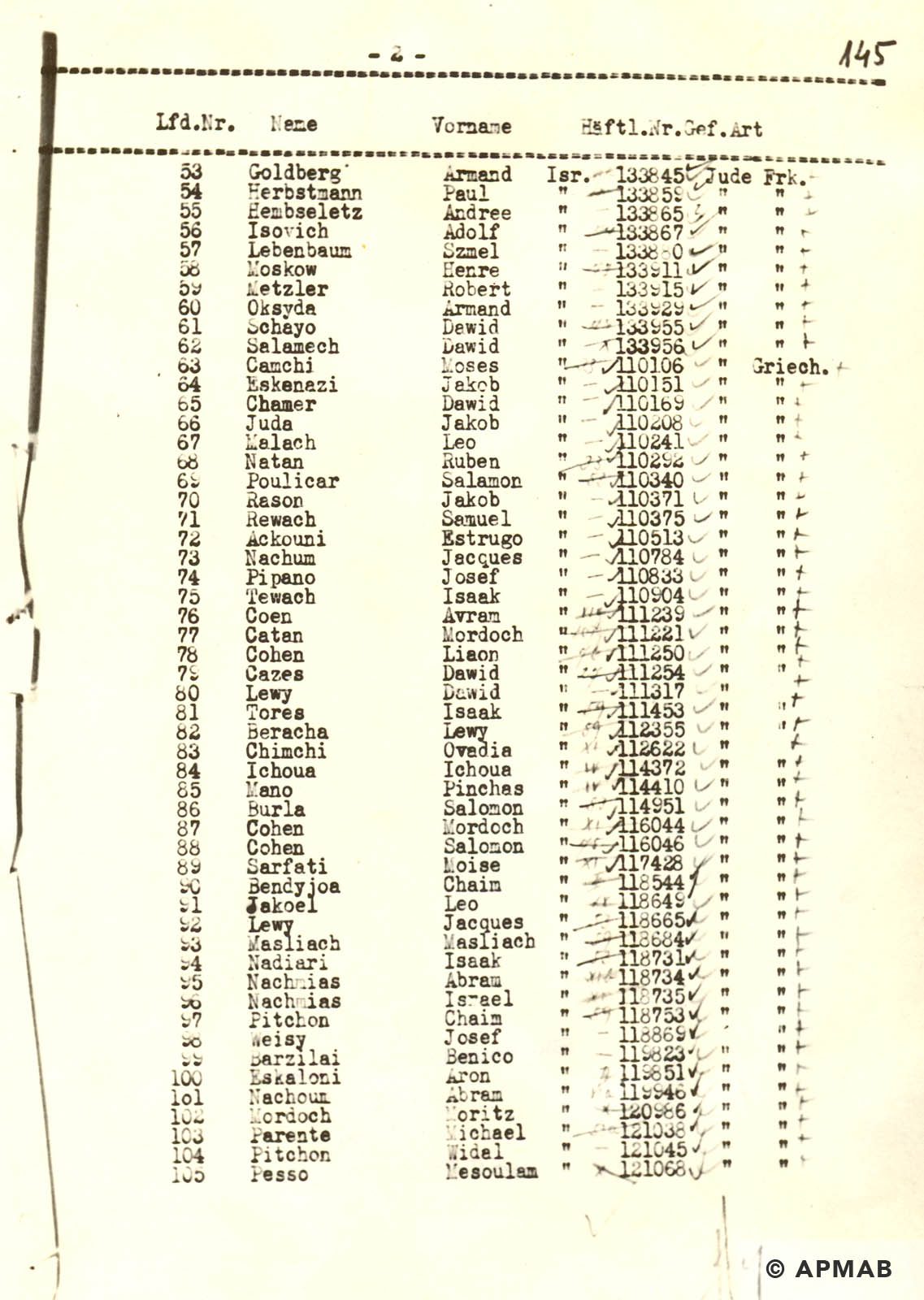

Mostly Jews from across Europe – from Greece, Poland, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, France and Germany.

Period of camp existence

15 June 1943 – 17 January 1945

Dissolution / Evacuation of the sub camp

On 17 January 1945 all prisoners were marched on foot to the concentration camp Gross-Rosen, later evacuated to the concentration camp Buchenwald.

Dates of site visits by Tiergartenstrasse4 Association

June 2006, October 2006, December 2006, March 2007, September 2008

Memorialisation

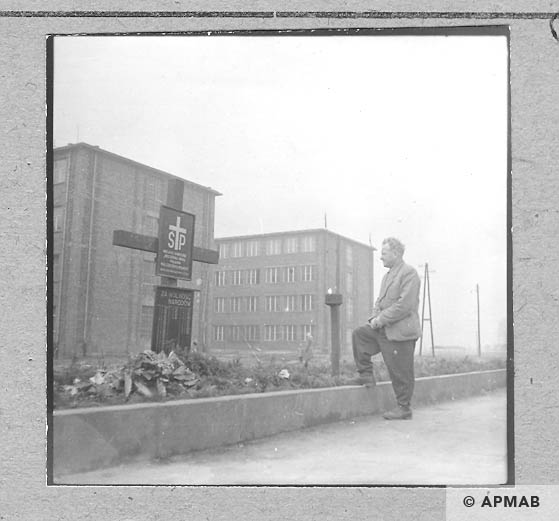

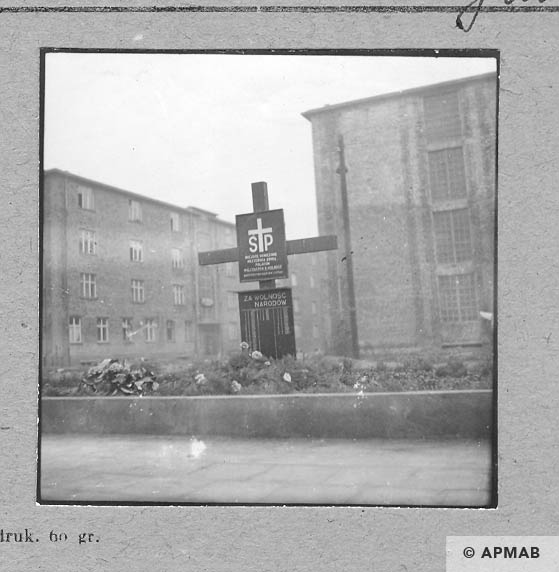

At ul Grunwaldzka in Jaworzno there is a stone monument erected on a mass war grave for the prisoners of Auschwitz-Birkenau shot on January 17, 1945 by SS men during the evacuation.

Explore more

The History

The history of the companies and the places prisoners worked, the sub camps, the SS guards and memorialisation of the sites.

The History of the Power Plants in Jaworzno

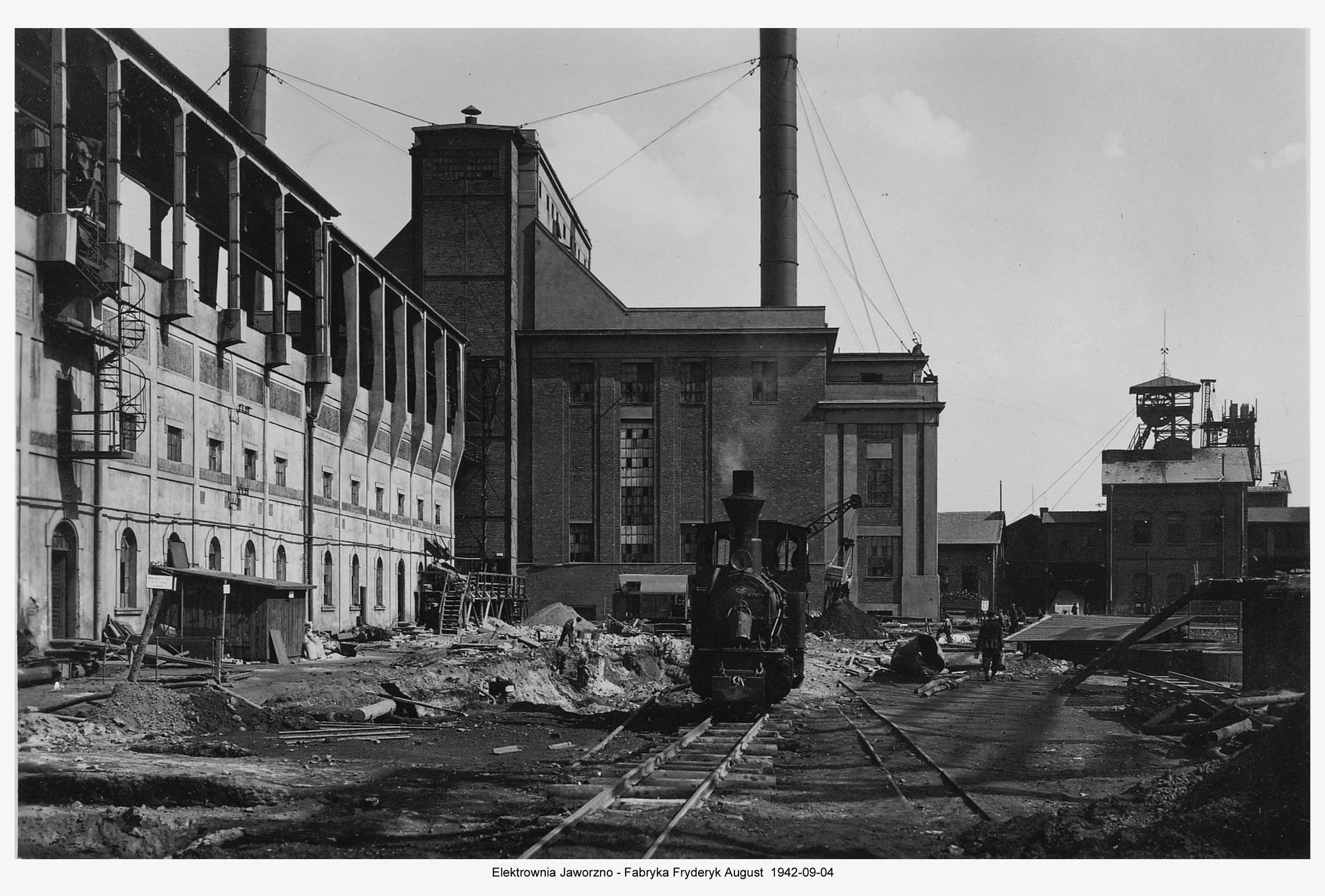

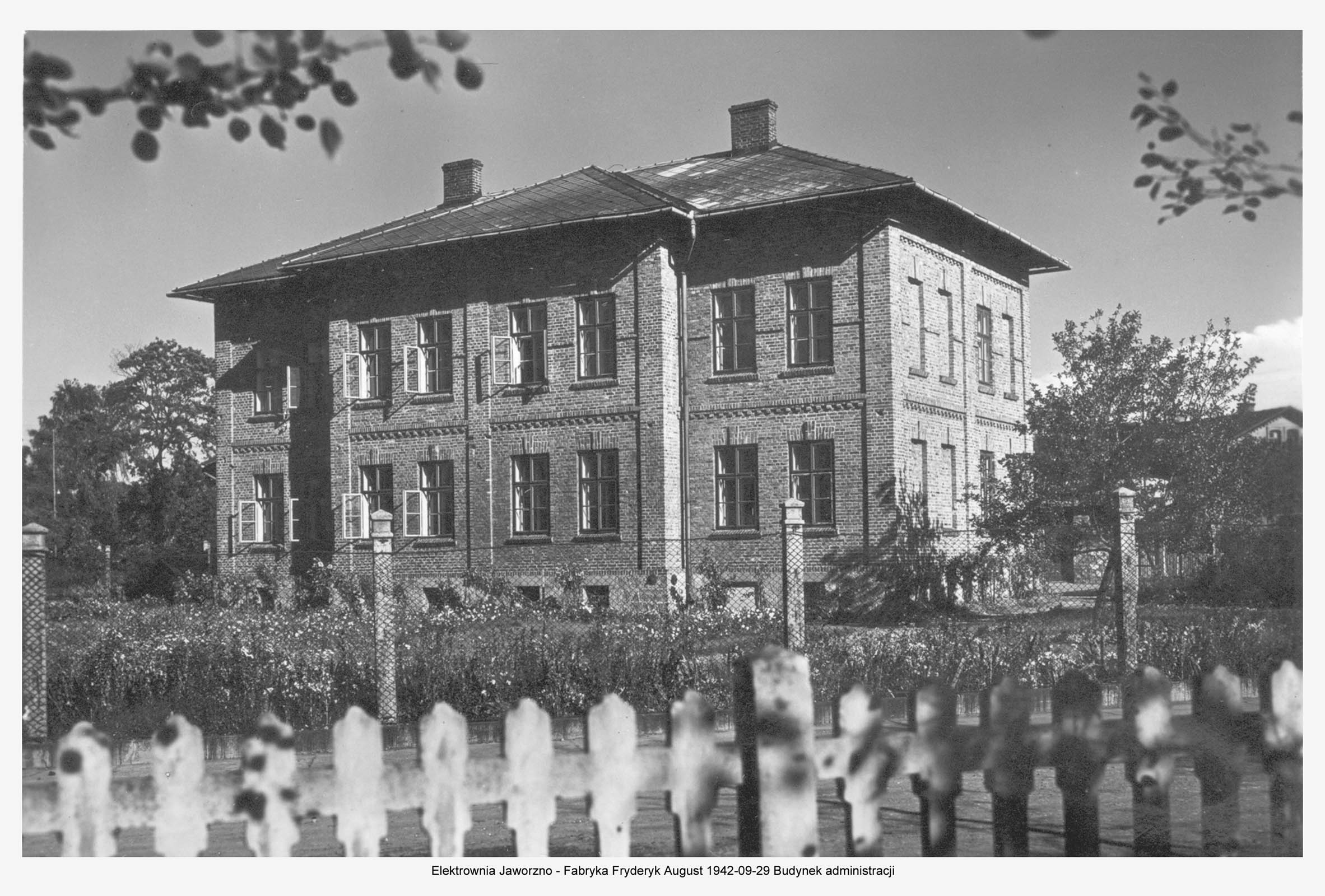

The beginnings of the power industry in Jaworzno date back to 1898 when two direct electricity generators with a total power of 320 KW were installed at the Rudolf mine shaft of Jaworznicki Gwarectwa. They provided lighting for the mine and nearby houses. The development of mining in Jaworzno, required the development of an energy infrastructure. In 1903, near the Frederick August mine shaft, a new boiler room with two boilers was constructed within the buildings of today’s Jaworzno power plant. The turbine installed there had a power of 800 kW and generated a voltage of 3150 V. In 1912-1916 the power plant was enriched with further boilers and turbine sets giving a total power of 7.62 MW.

After the First World War Jaworzno became part of Poland. Further investment in and expansion of the power plant was undertaken at the end of the 1920s. In 1930, a new section of the power plant was launched, in which 4 boilers and a 11.5 MW turbine were installed. The plant’s total capacity increased to 19.12 MW. In addition to the Jaworzno mines, electricity was supplied to Krakow, the Olkusz Powiat and seven communes of the Chrzanów Powiat. In 1938 another 20 MW turbine was launched, which gave the plant a total power of 39.12 MW.

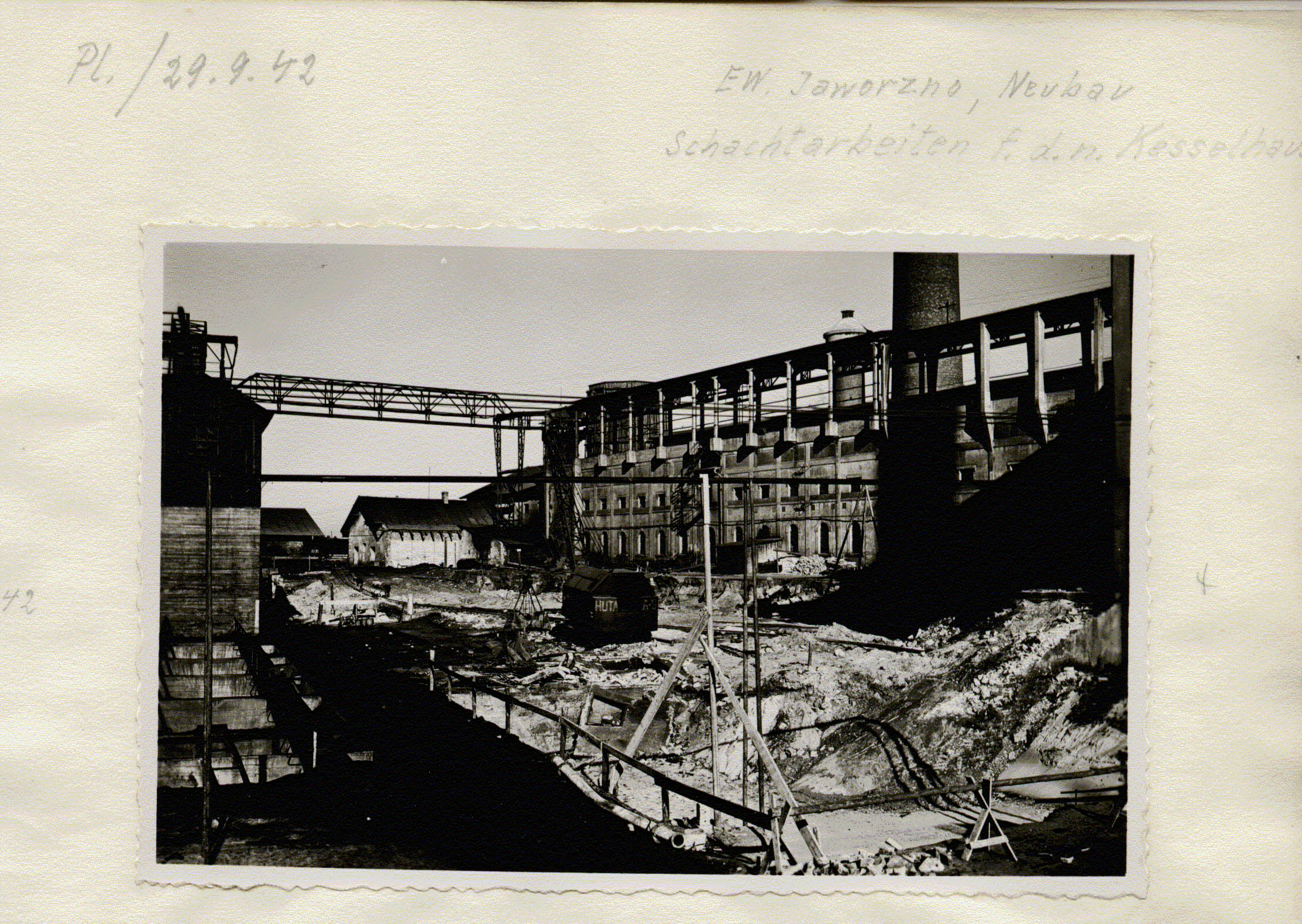

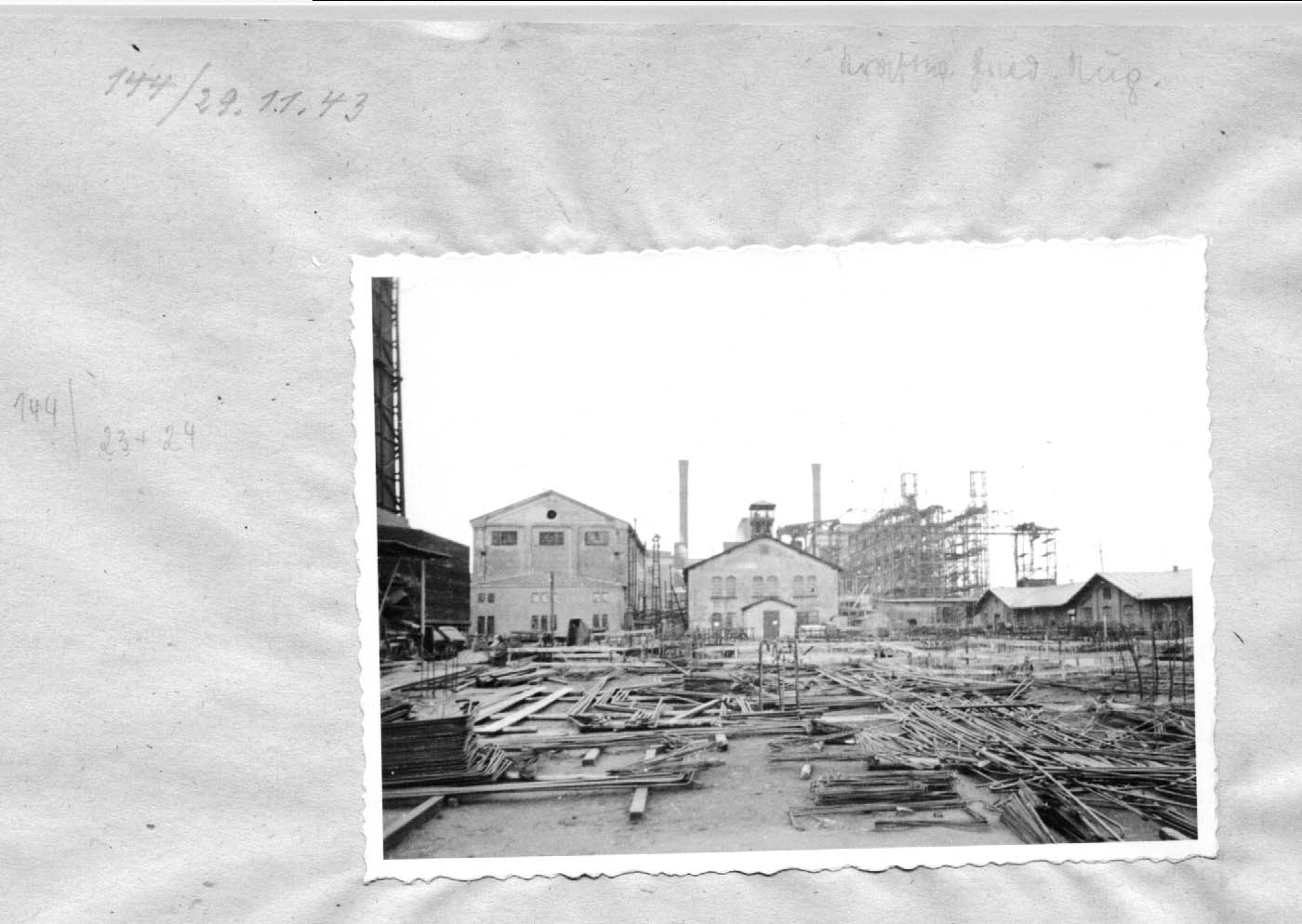

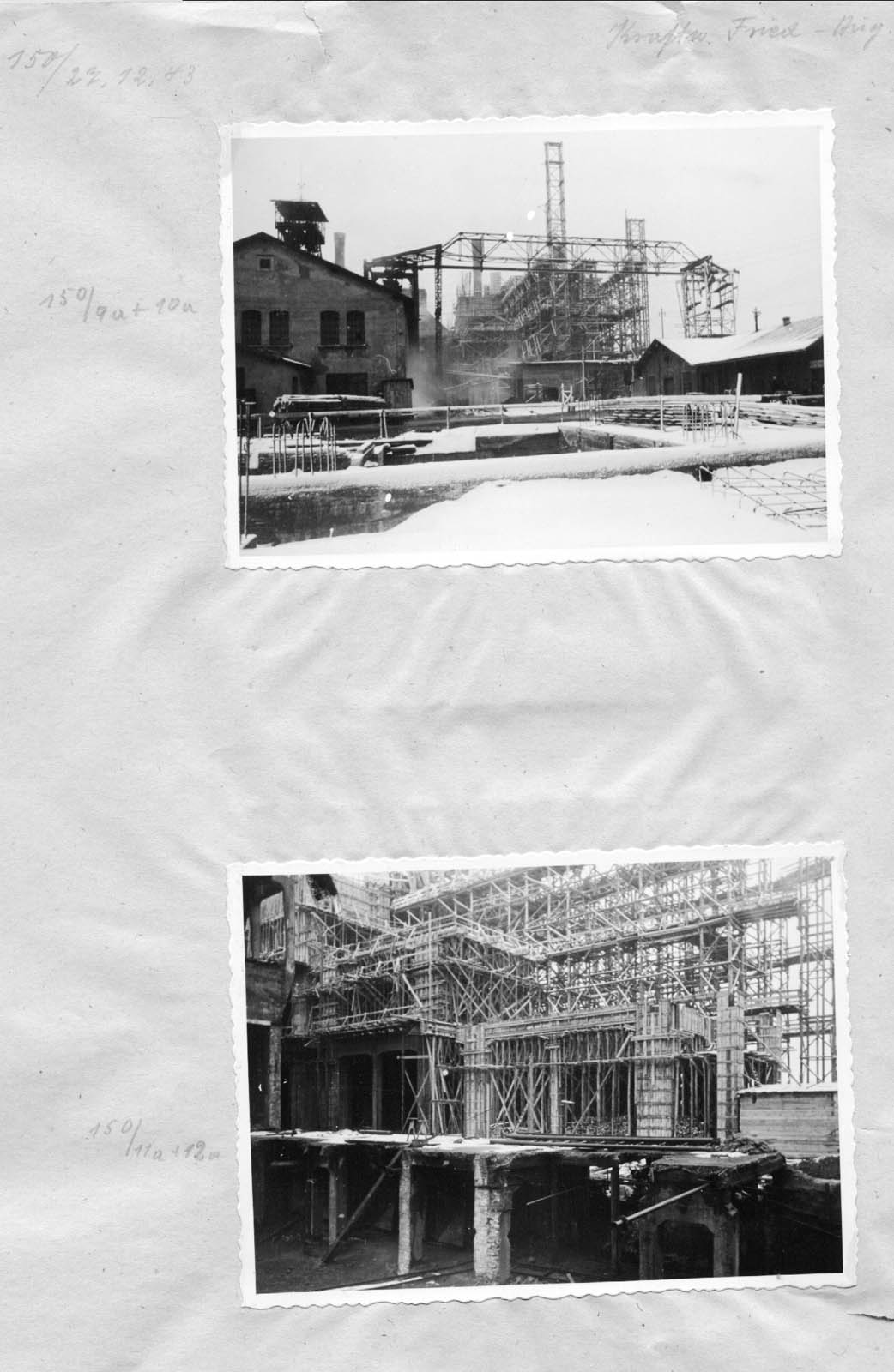

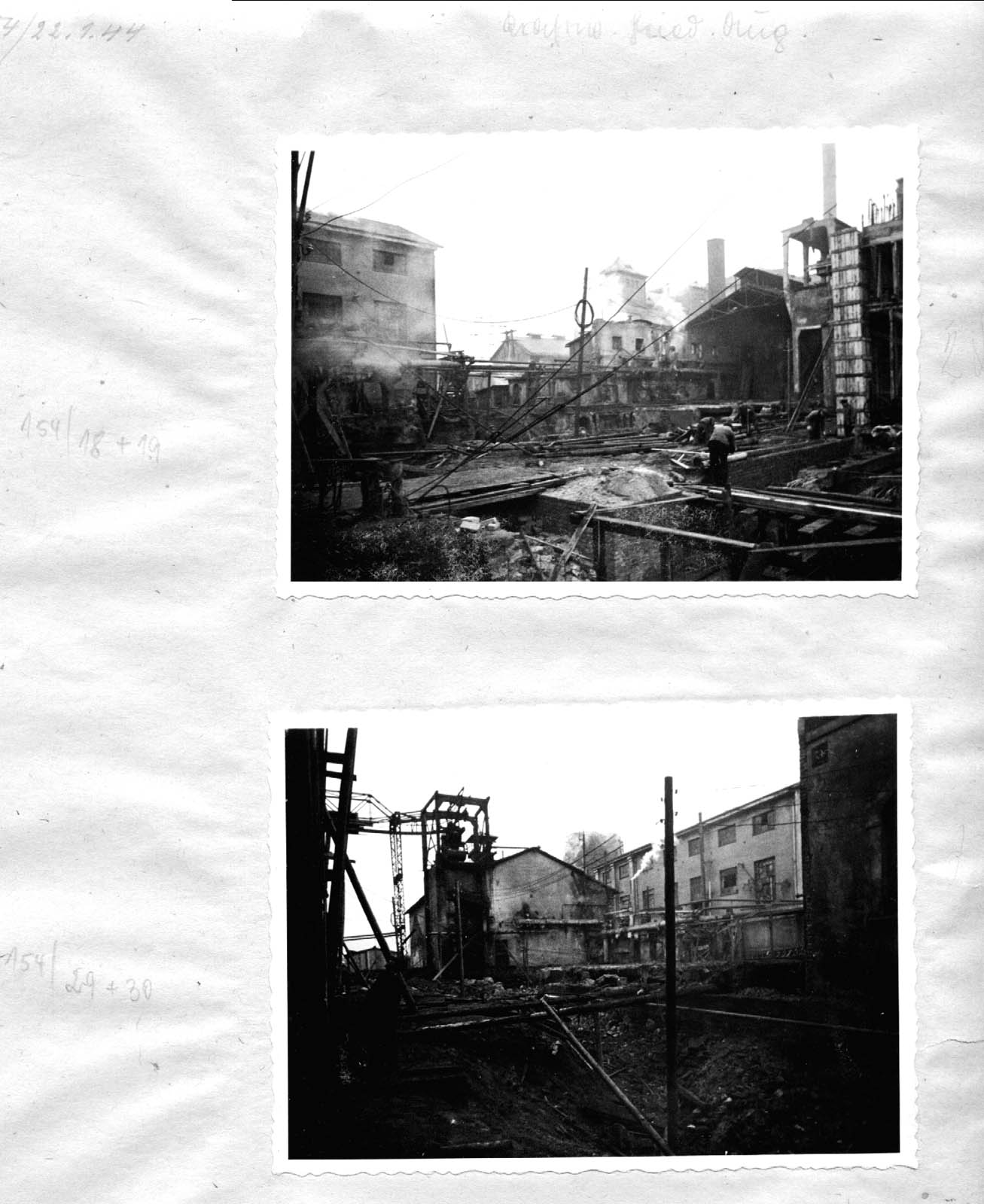

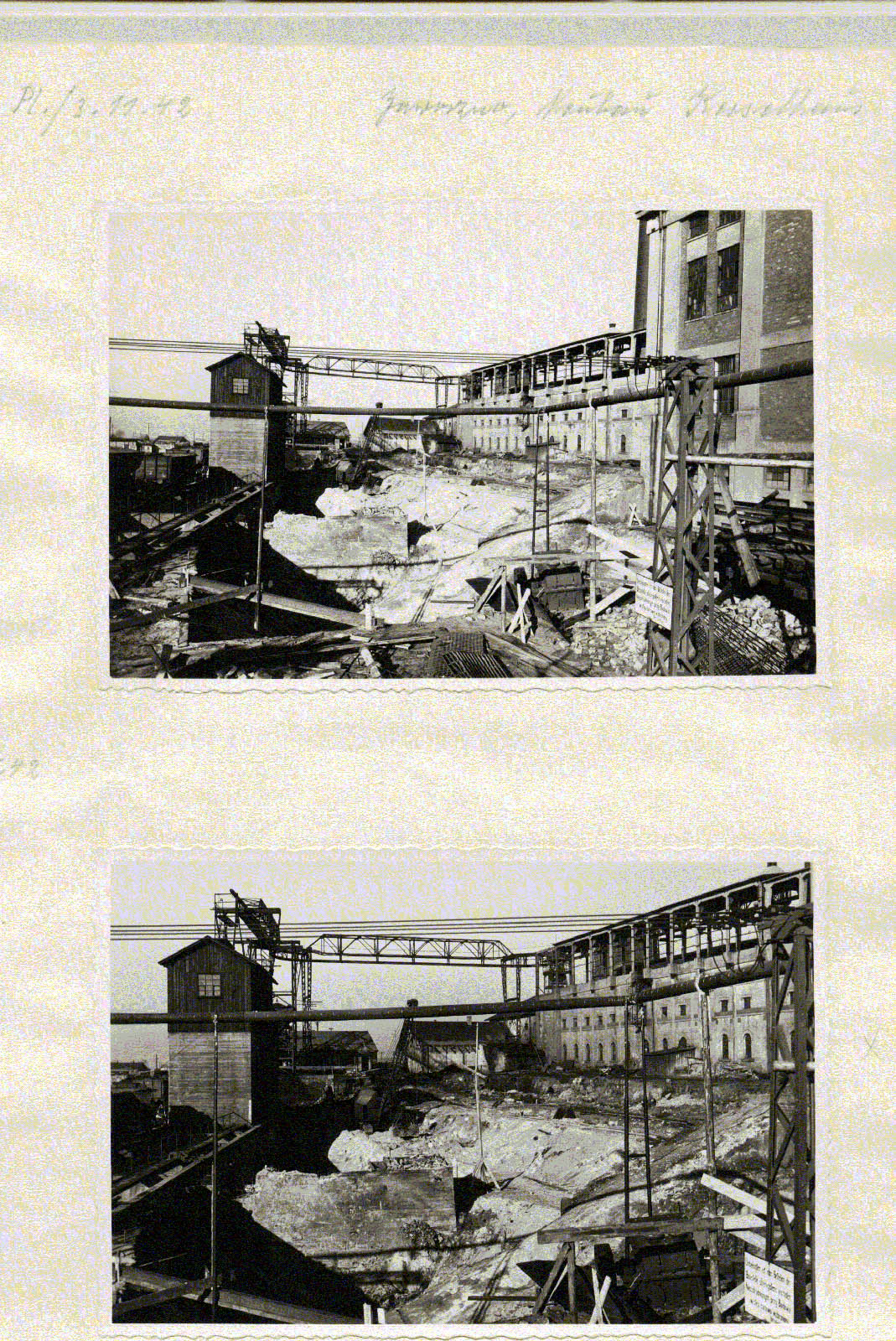

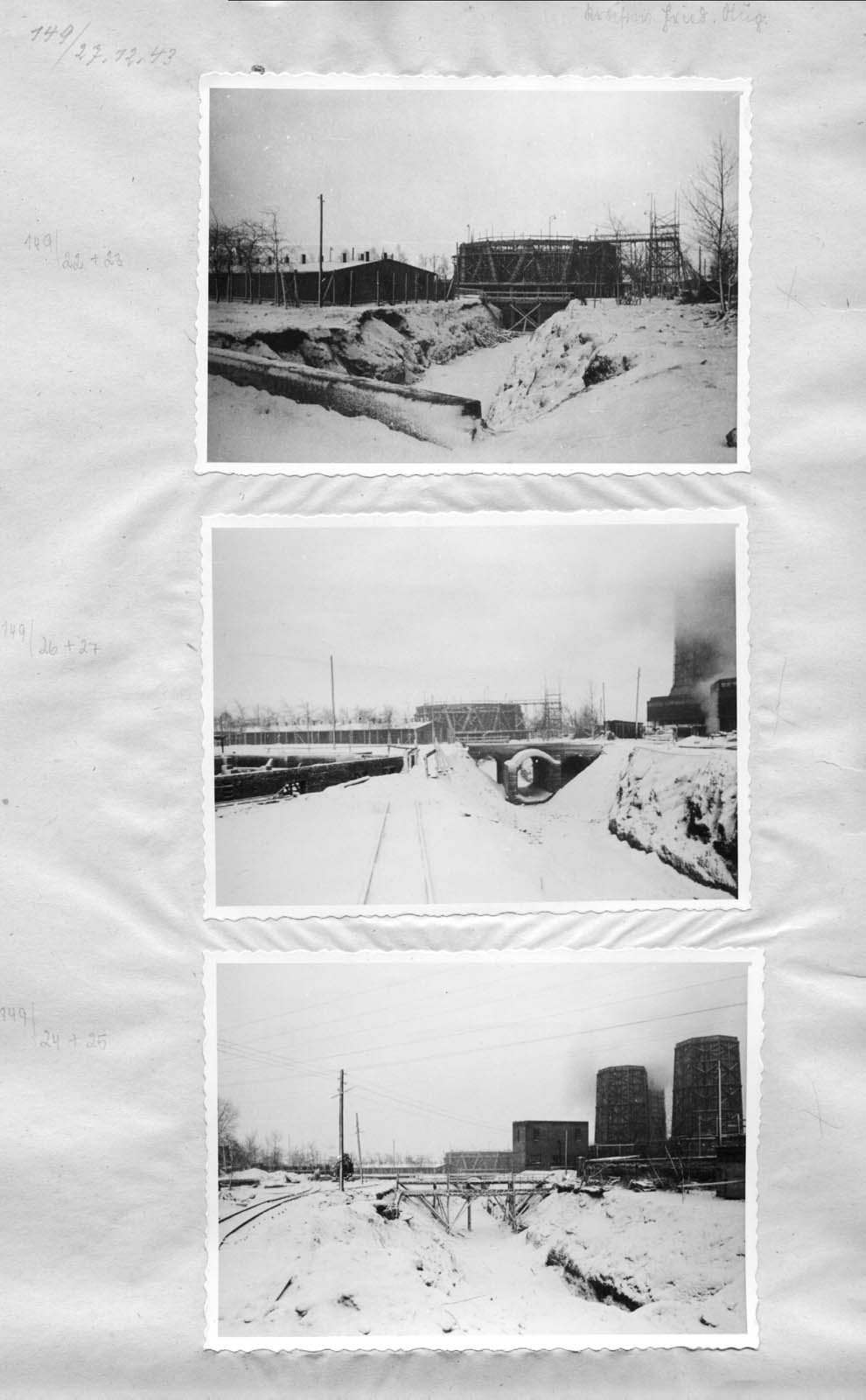

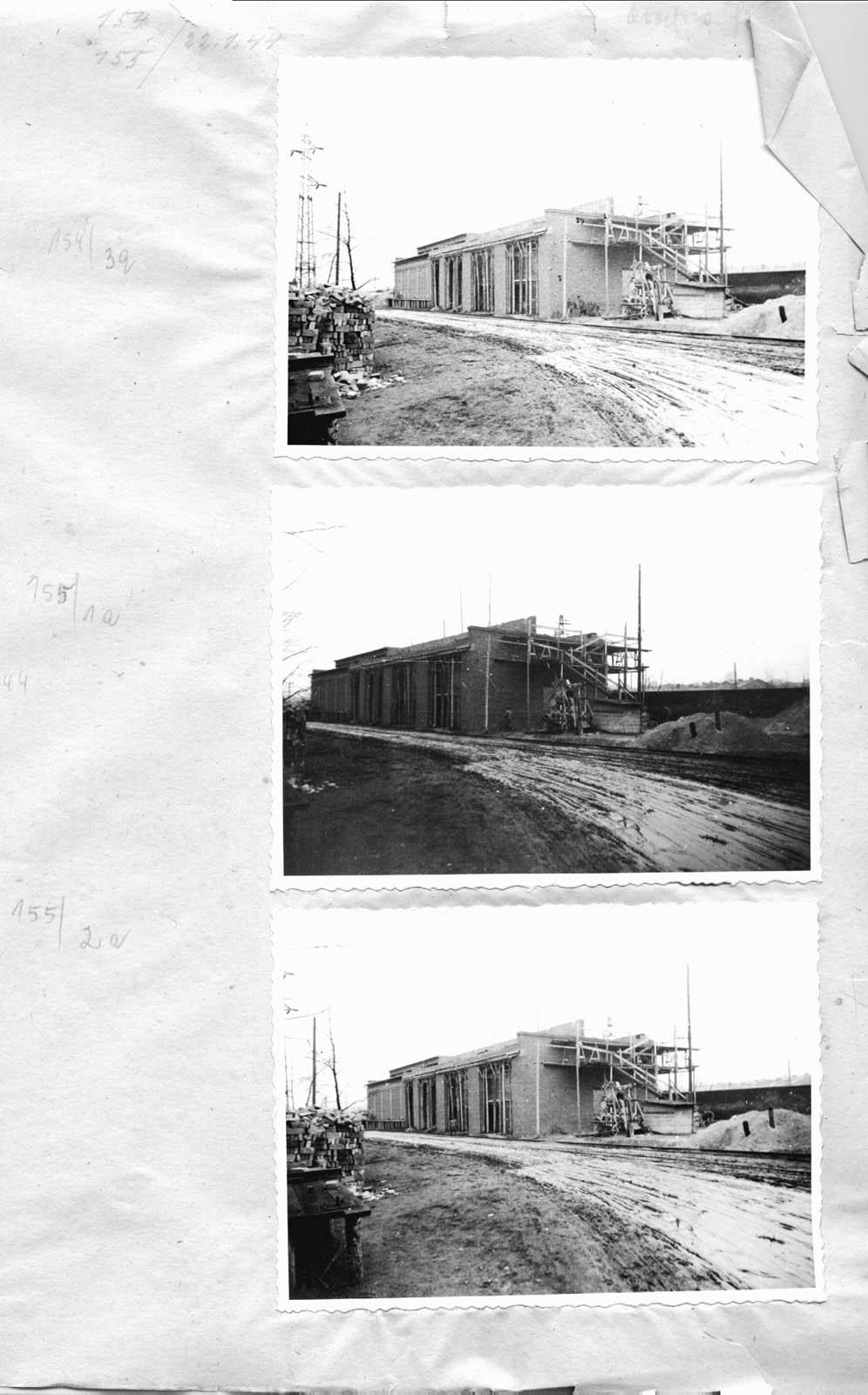

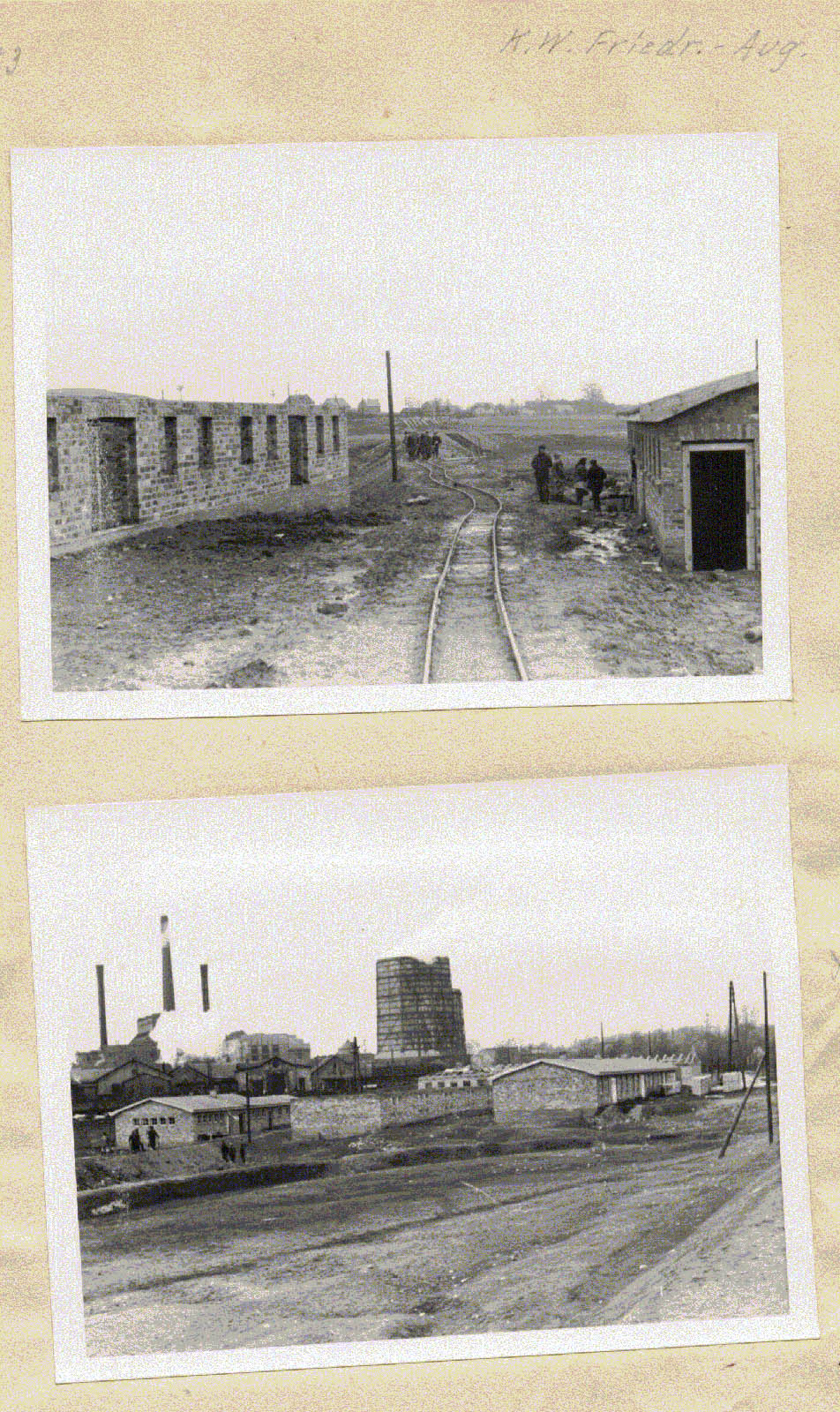

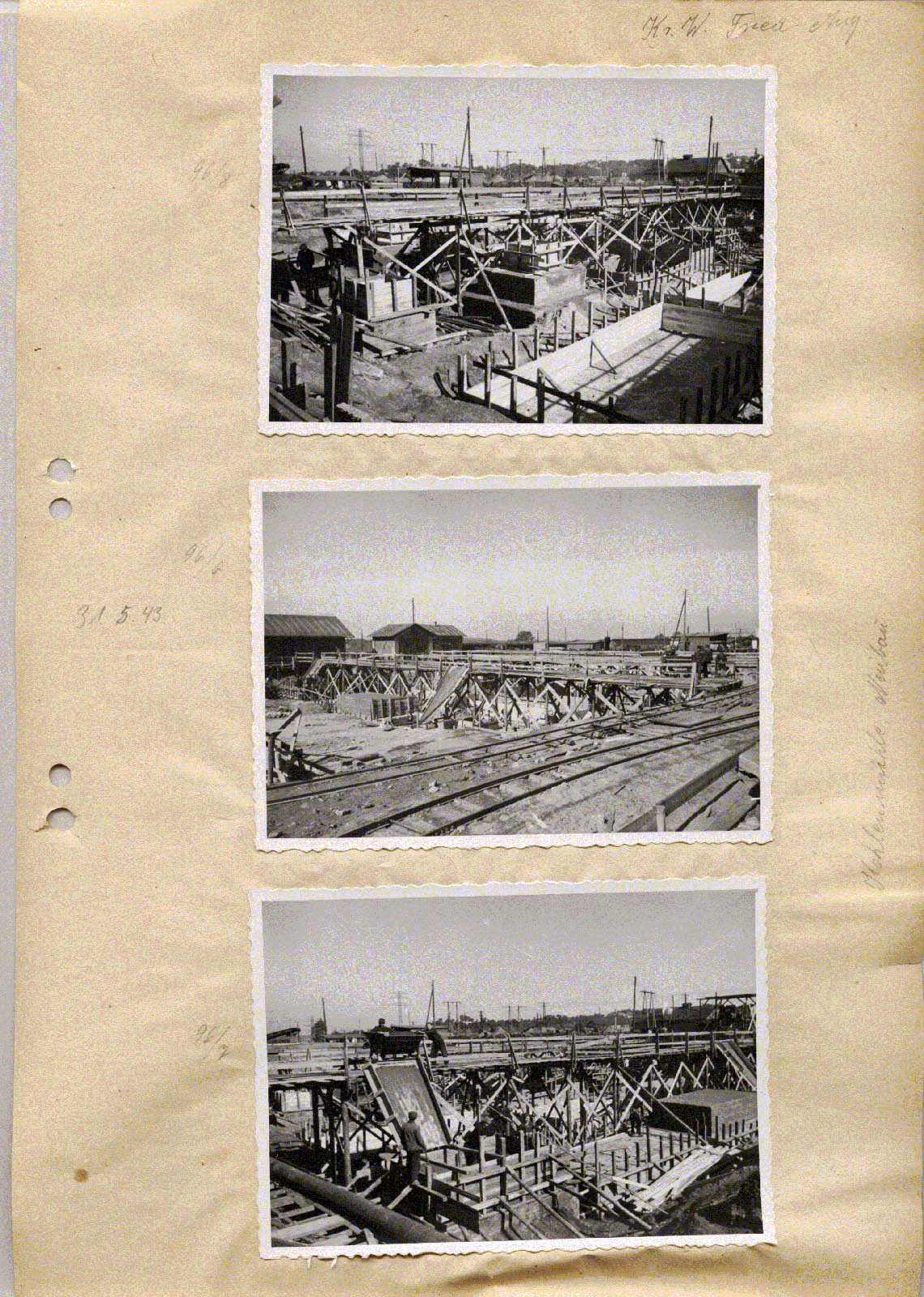

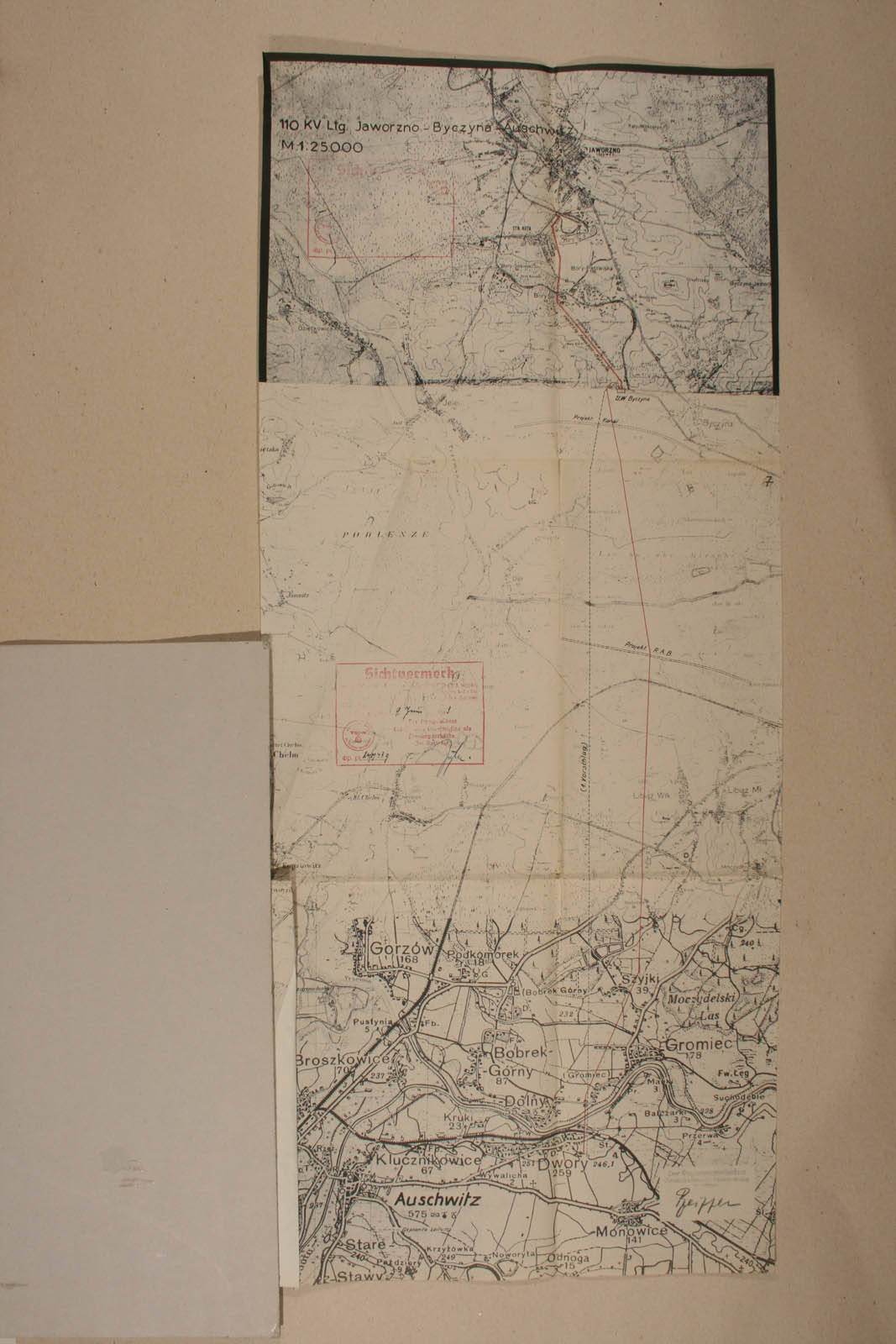

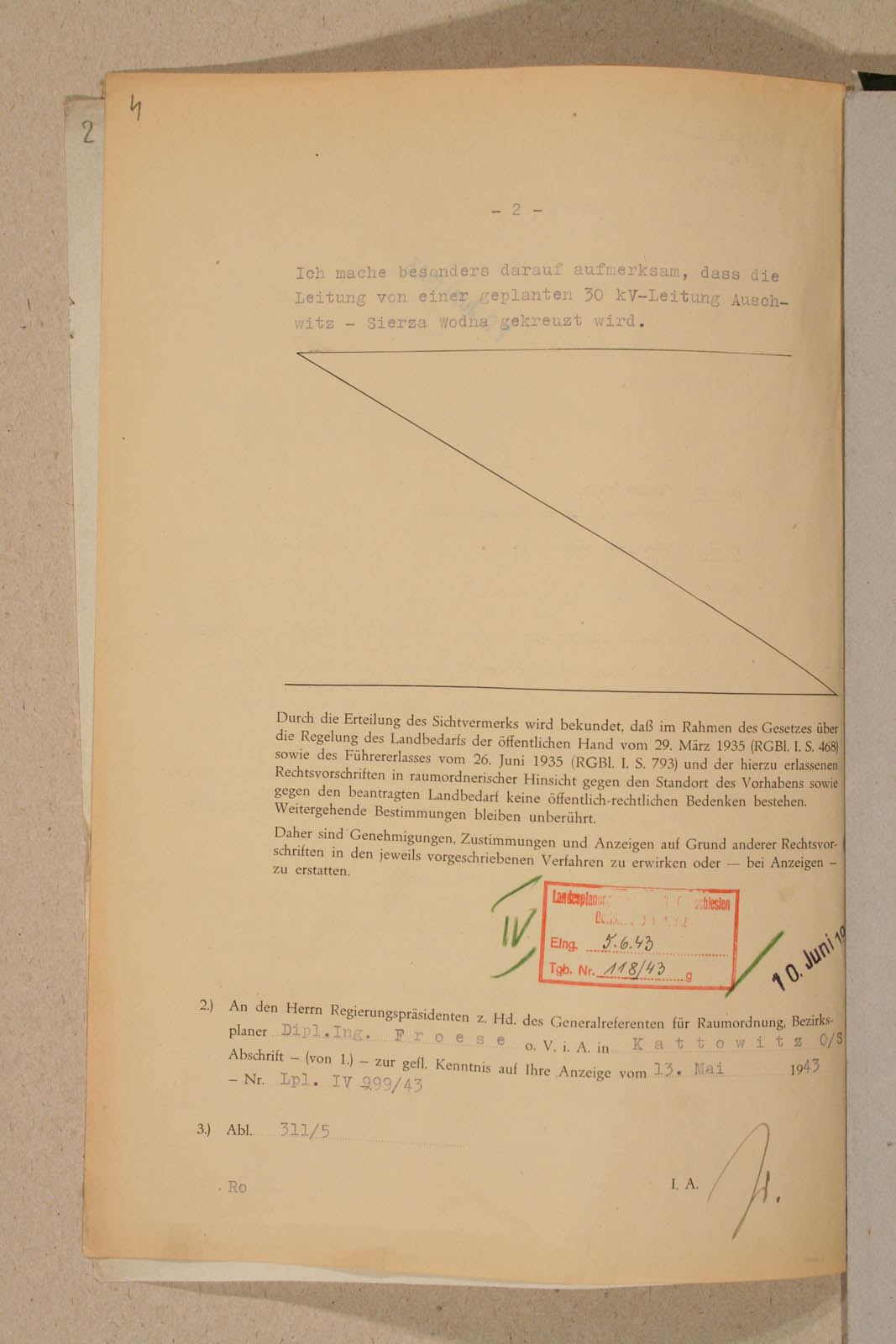

During World War II, the Kraftwerk Friedrich-August became one of the most important power plants in Upper Silesia. It was managed by the joint-stock company Energieversorgung Oberschlesien Aktiengesellschaft (EVO) based in Katowice, appointed by the Reich Inspector General for Water and Energy – Albert Speer. An expansion of the Kraftwerk Friedrich-August began in 1942 with demolition and construction works. A new boiler room was constructed, and the assembly of the boilers started. A double-track high-voltage line was also built connecting the power plant with Chorzów. At the same time, the Siemens design office developed plans for the construction of a completely new power plant in Jaworzno, Kraftwerk Wilhelm. This new power plant was to be built, with labour including prisoners of the Neu-Dachs sub camp.

The Post War History of the Power Plants in Jaworzno

After the war in the years 1948-1952 the first modernization of the power plant was undertaken, and the total capacity of the plant was increased to 110.3 MW. The power plant named Jaworzno I was included in the country’s energy system. At the same time, construction works began on the Jaworzno II power plant with equipment supplied from the USSR. The Jaworzno II Power Plant was commissioned in July 1953, and three years later the capacity reached 280 MW.

On January 1, 1971, the Zespół Elektrowni Jaworzno was created, consisting of the Jaworzno I and Jaworzno II power plants.

In 1972-1976 a 300 m high chimney was built at the Jaworzno III Power Plant. It is the highest structure of this type in Poland and one of the highest in Europe.[1]

In 1989, Zespół Elektrowni Jaworzno was included in the Katowice Heat and Power Plant Complex.

In December 1995 a sole shareholder company of the State Treasury was established, Elektrownia Jaworzno III S.A., which included: Elektrownia Jaworzno III and Zespół Elektrowni Jaworzno. The Jaworzno II power plant was modernized while the Jaworzno I Power Plant was closed as it did not meet ecological standards.

In November 1998, the company Zakład-Górniczo Energetyczny “Sobieski Jaworzno III” was established with the majority shareholding of the Jaworzno III Power Plant, belonging to Południowy Koncern Energetyczny S.A. Thus, the power plant ceased to operate as an independent entity. The Jaworzno III Power Plant is today the company’s largest plant and is one of the most modern and ecologically compliant power plants in Poland.

[1] There is another 300 m high chimney in Poland at the Rybnik Power Plant in Upper Silesia.

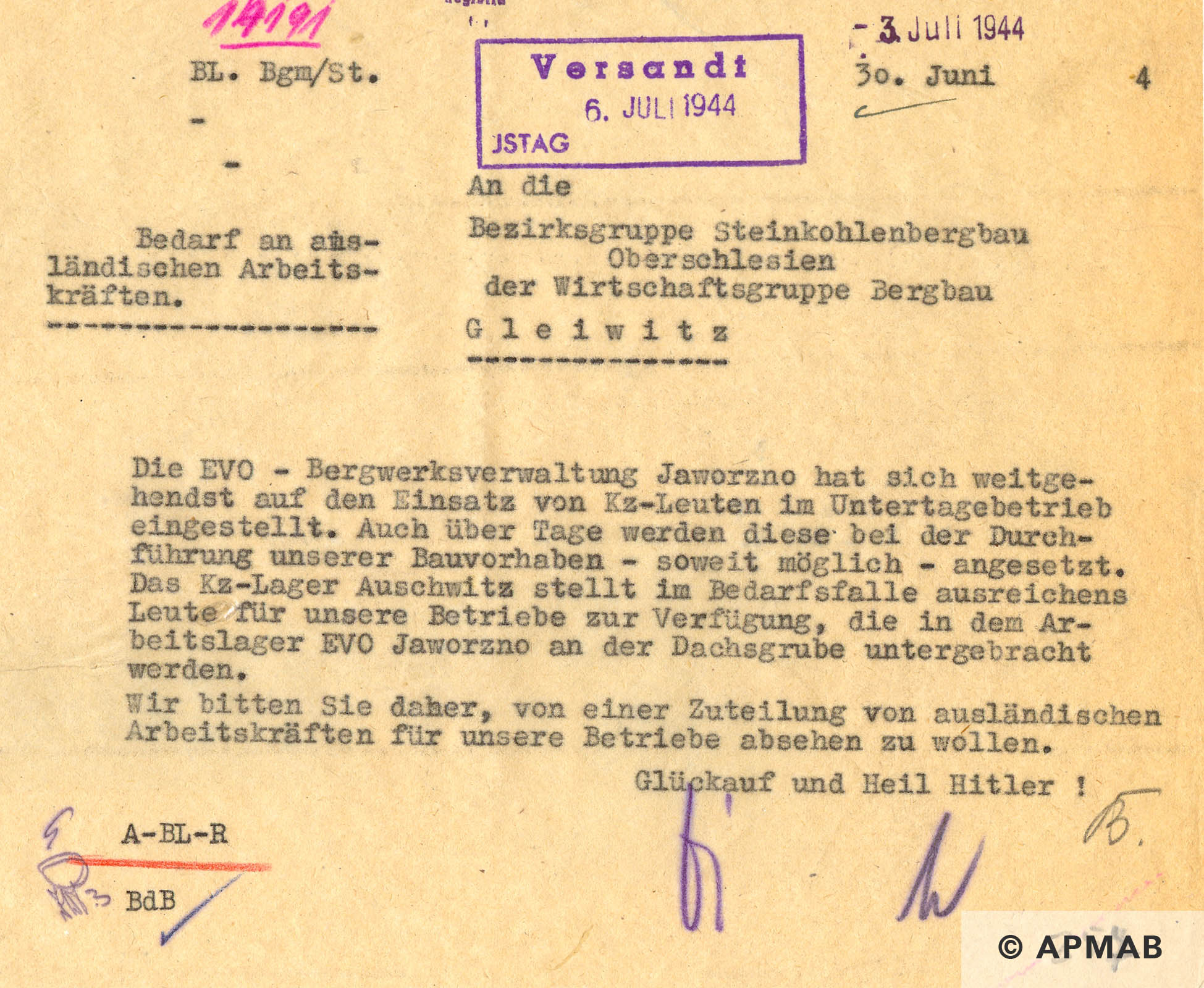

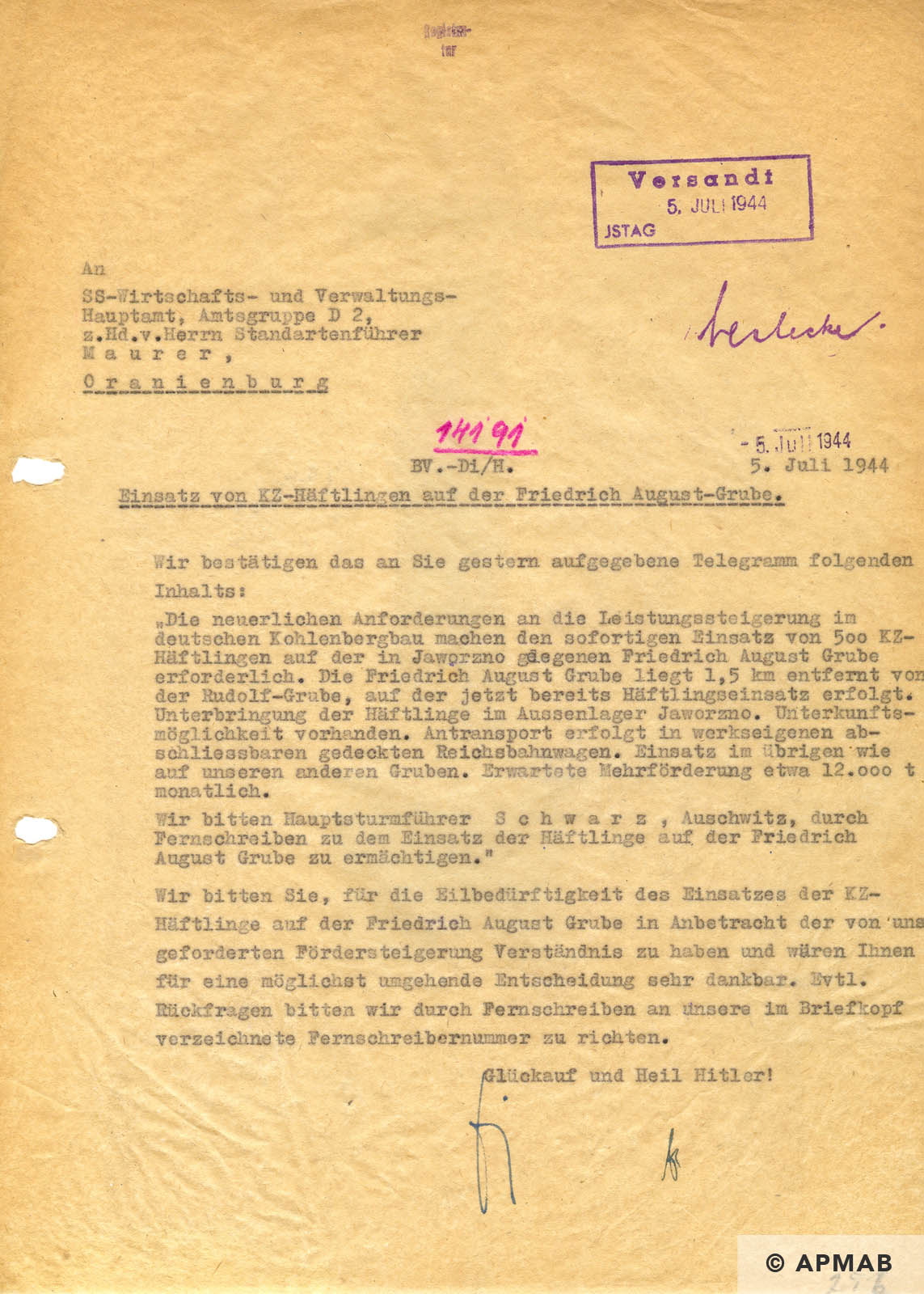

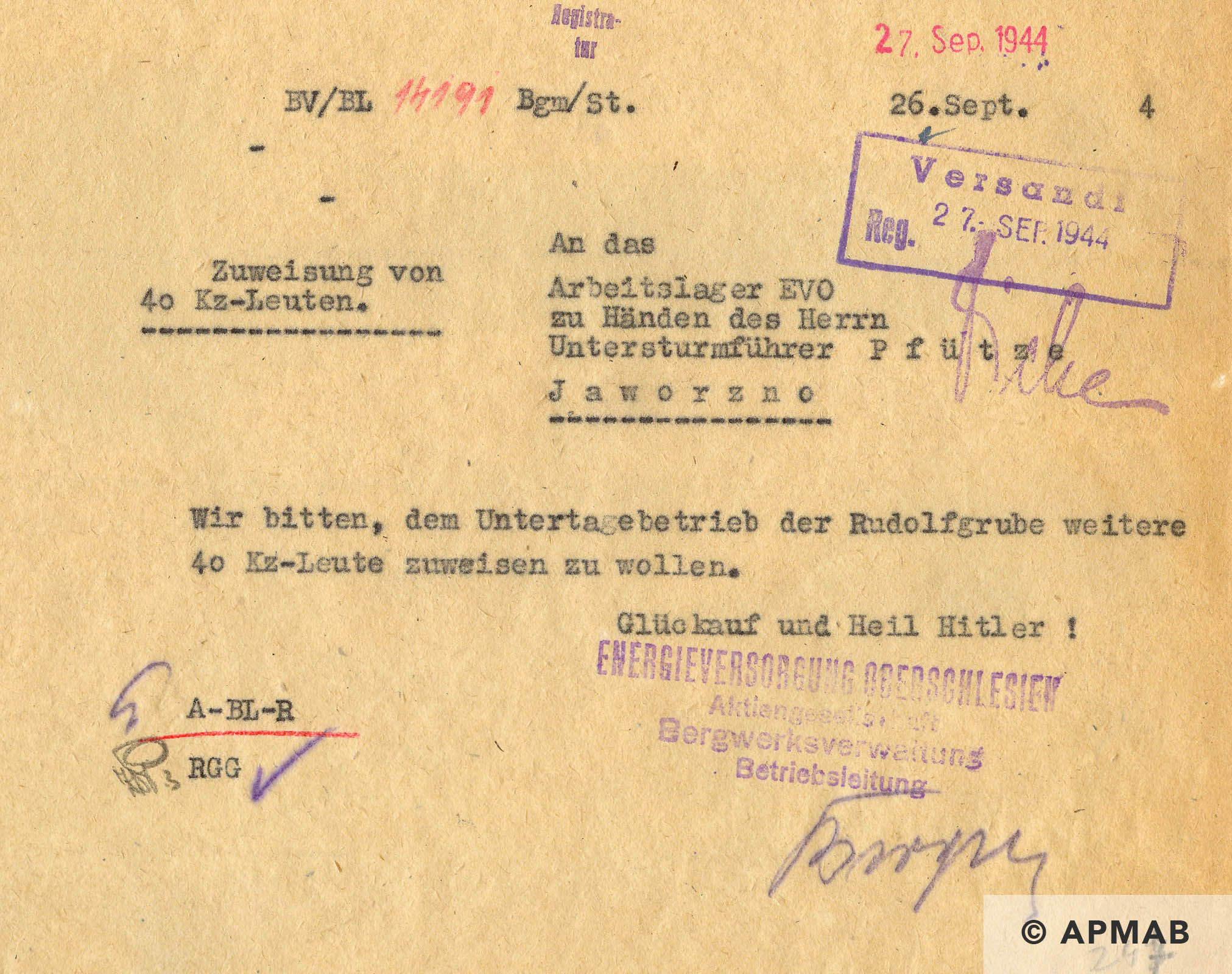

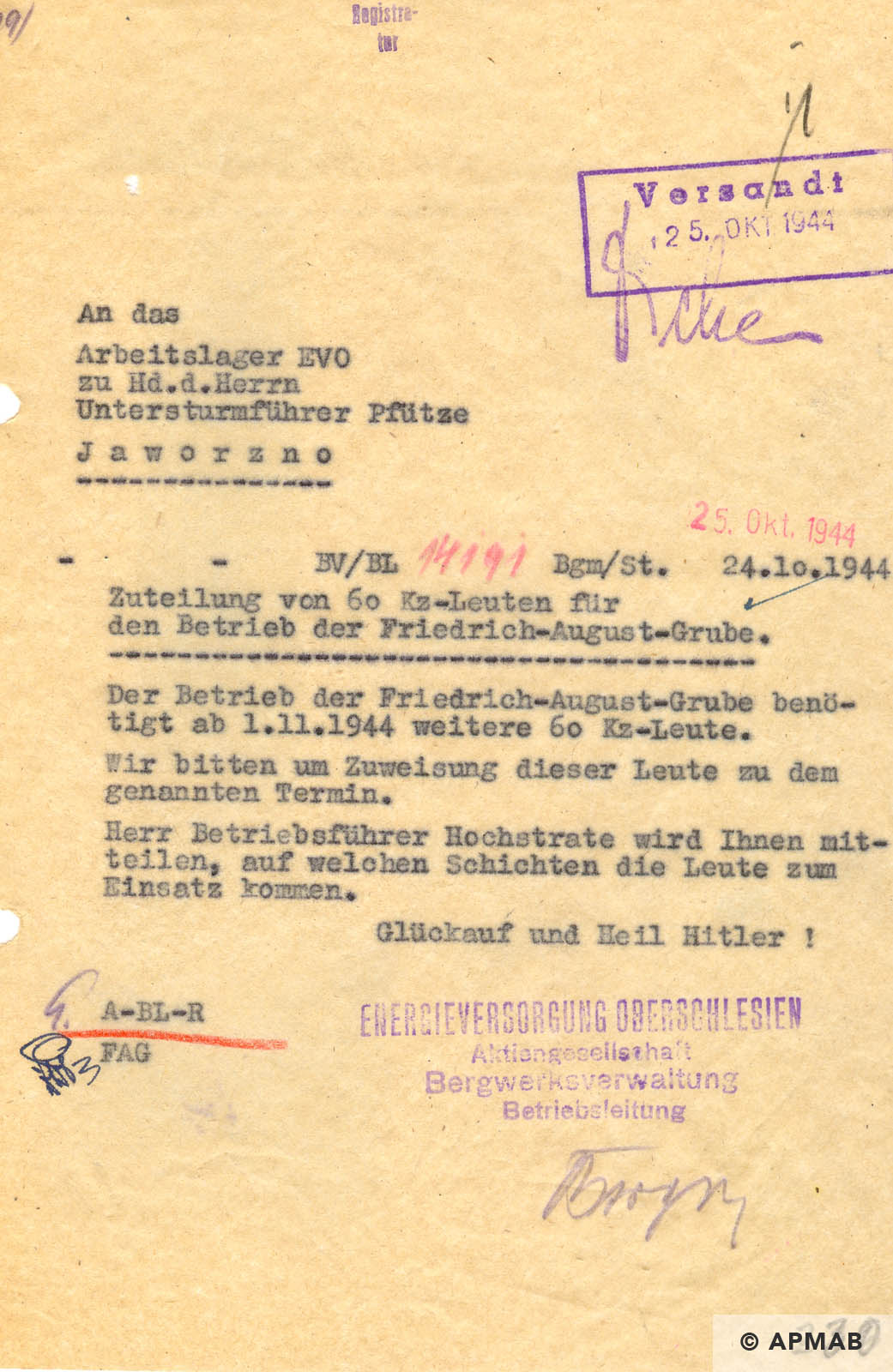

The History of the Sub Camp Neu-Dachs

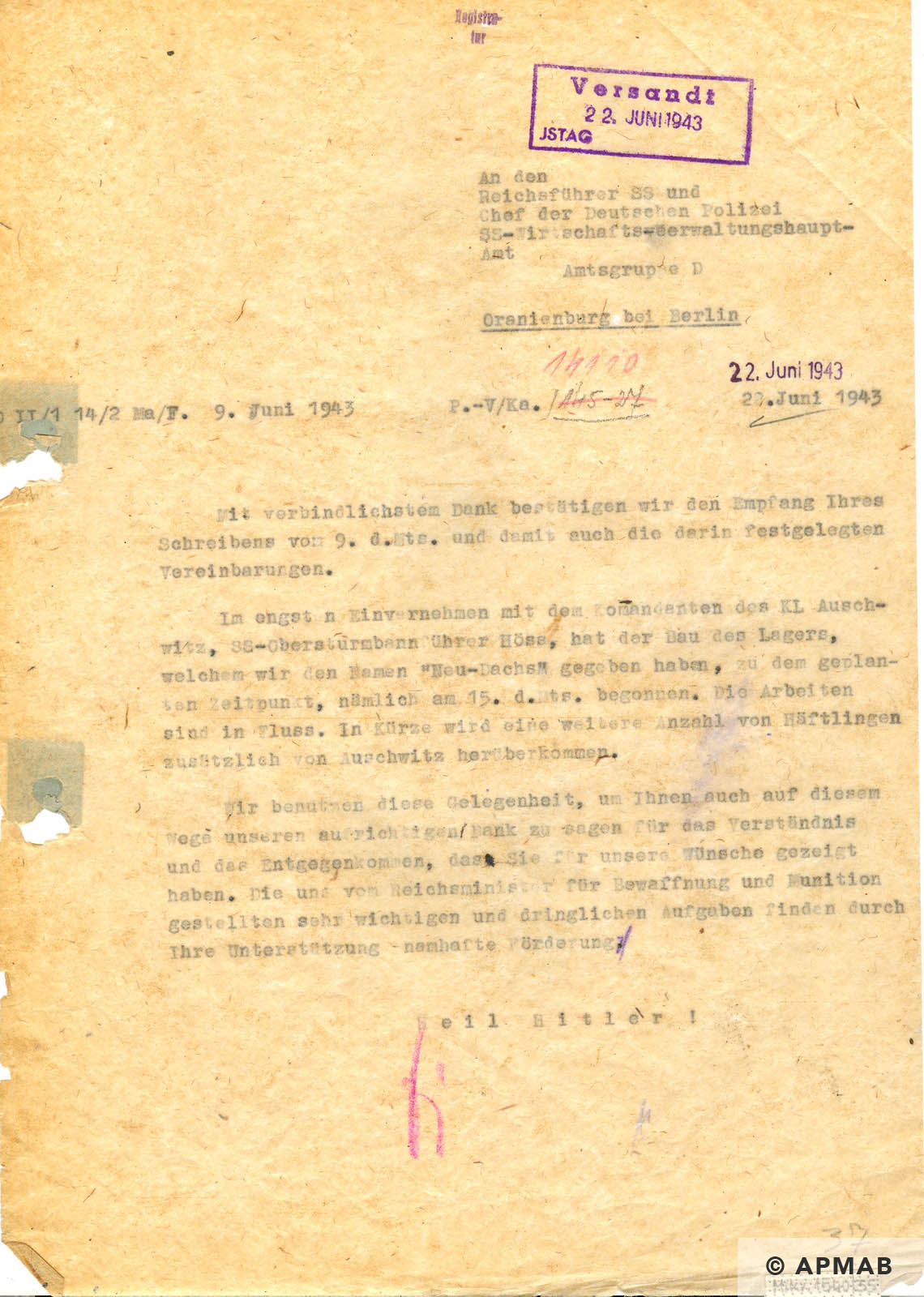

The Auschwitz sub camp in Jaworzno was set up on the initiative of the Energieverrsorgung Oberschlesien Aktiengesellschaft (EVO) from Katowice, to provide labour for the expansion of the power plants in Silesia, requested by Albert Speer. One of the largest investments launched by EVO in March 1943 was the construction of a new thermal power plant Kraftwerk Wilhelm in Jaworzno. It was also necessary to expand the coal mines around Jaworzno: Rudolfgrube, Friedrich-Augustgrube, Richardgrube, Leopoldgrube and Dachsgrube, to provide the coal for the power plant and the existing power plant Friedrich August. In March 1943 the management of EVO asked the commandant of Auschwitz to supply some 2,000 prisoners to be employed in the construction of the new power plant and expansion of the mines.[1]

The request from EVO was accepted by the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office and in agreement with the commandant of Auschwitz on June 15, 1943 the first 100 prisoners were transported to Jaworzno.

There were also a number of Working Parties of British commonwealth prisoners of war in Jaworzno from Stalag VIII B 344 in Lamsdorf. These included E561 Jaworzno / Tarnowtitz. railway depot loading and unloading trains and E 596 who worked in a coal mine in Jaworzno. [2] These British Commonwealth prisoners of war were to work alongside the Auschwitz prisoners of the sub camp Neu-Dachs.

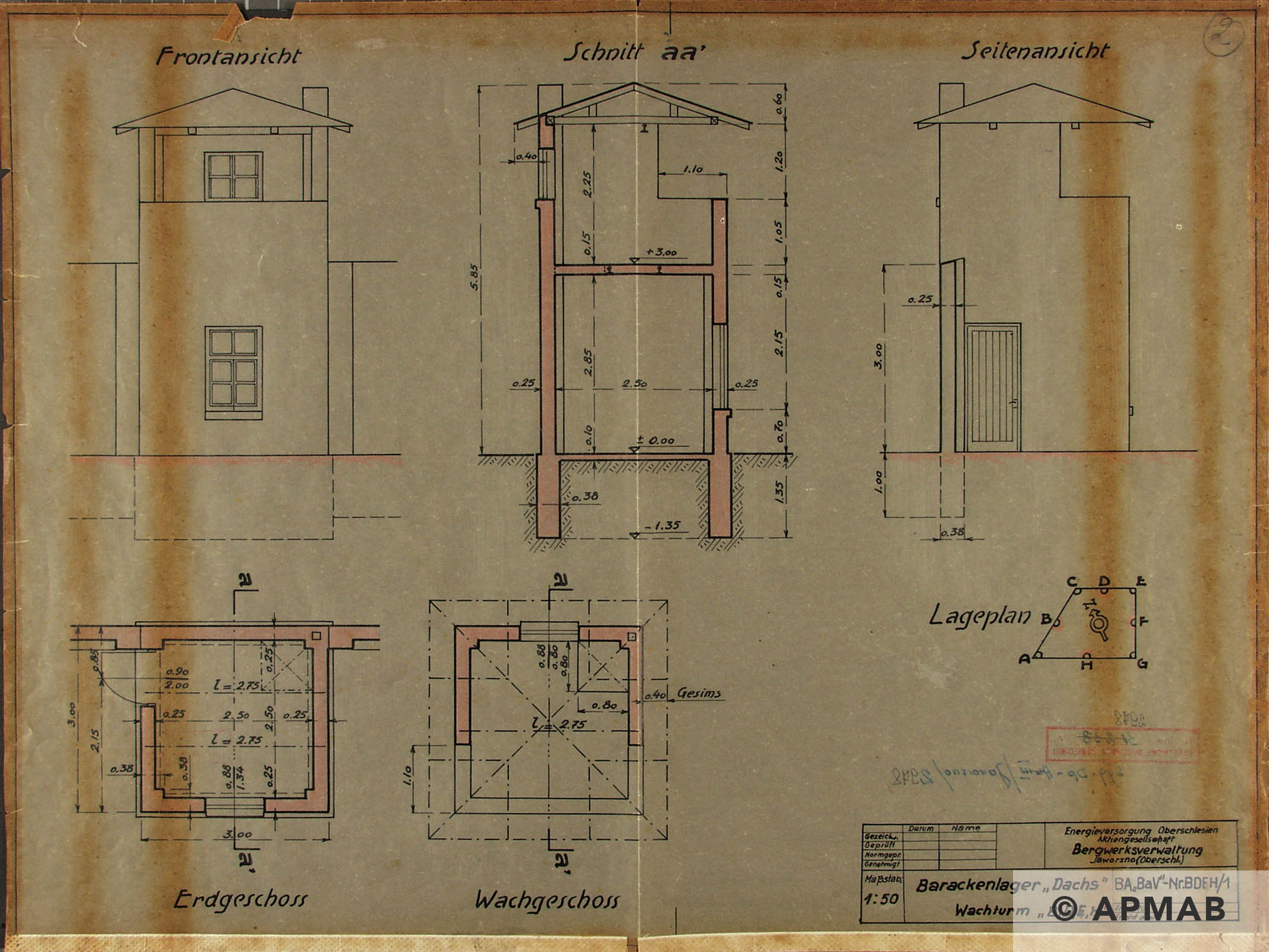

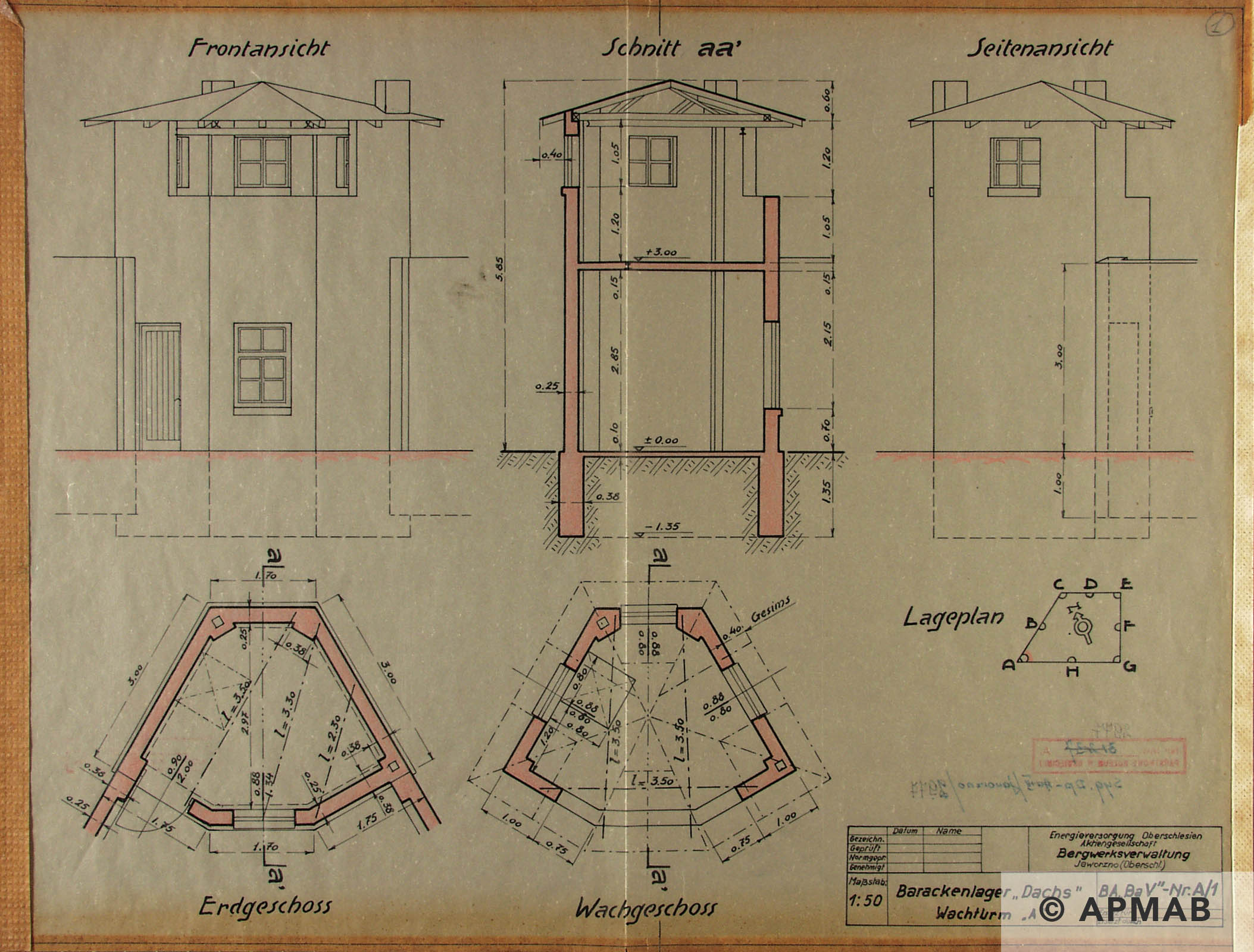

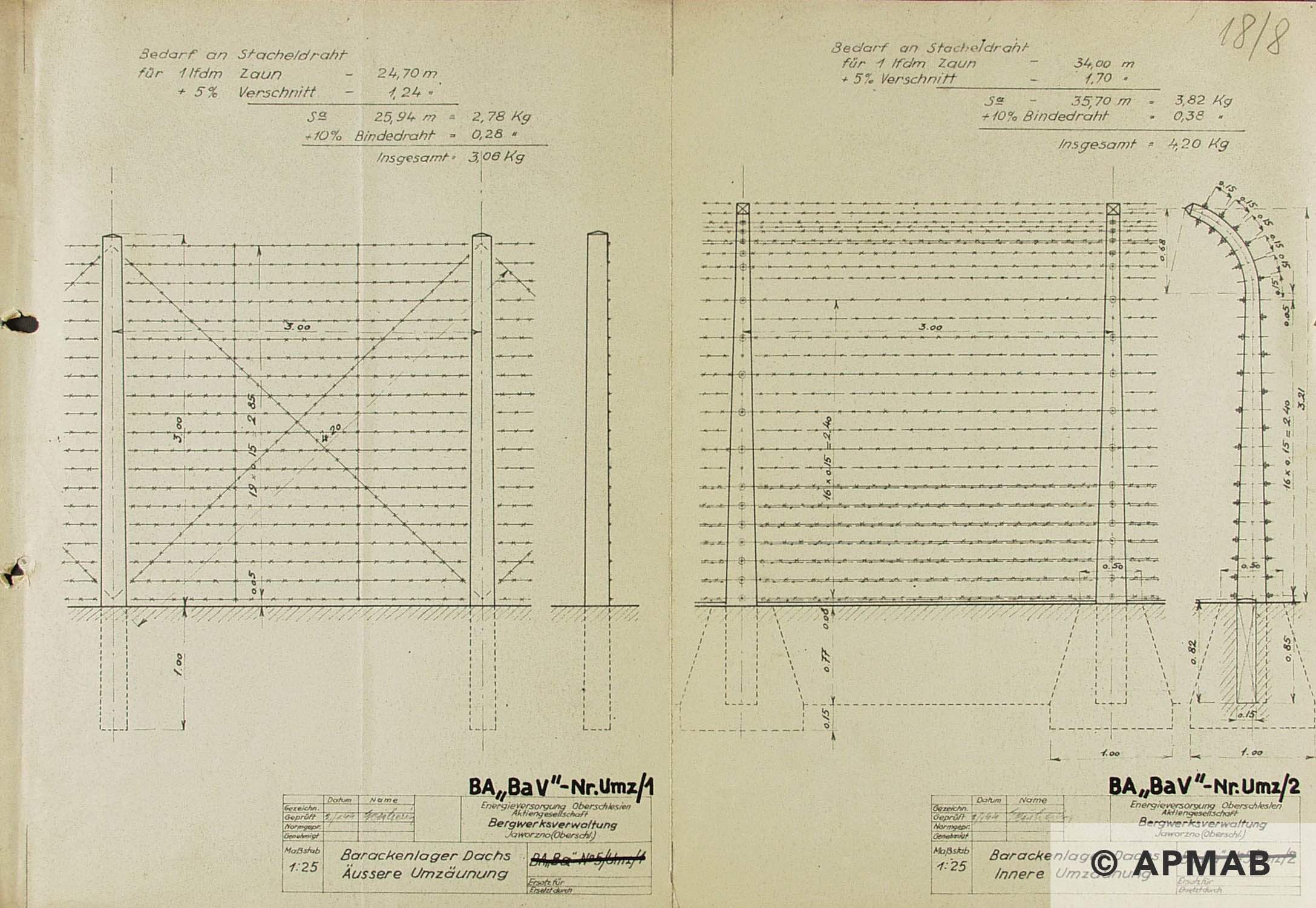

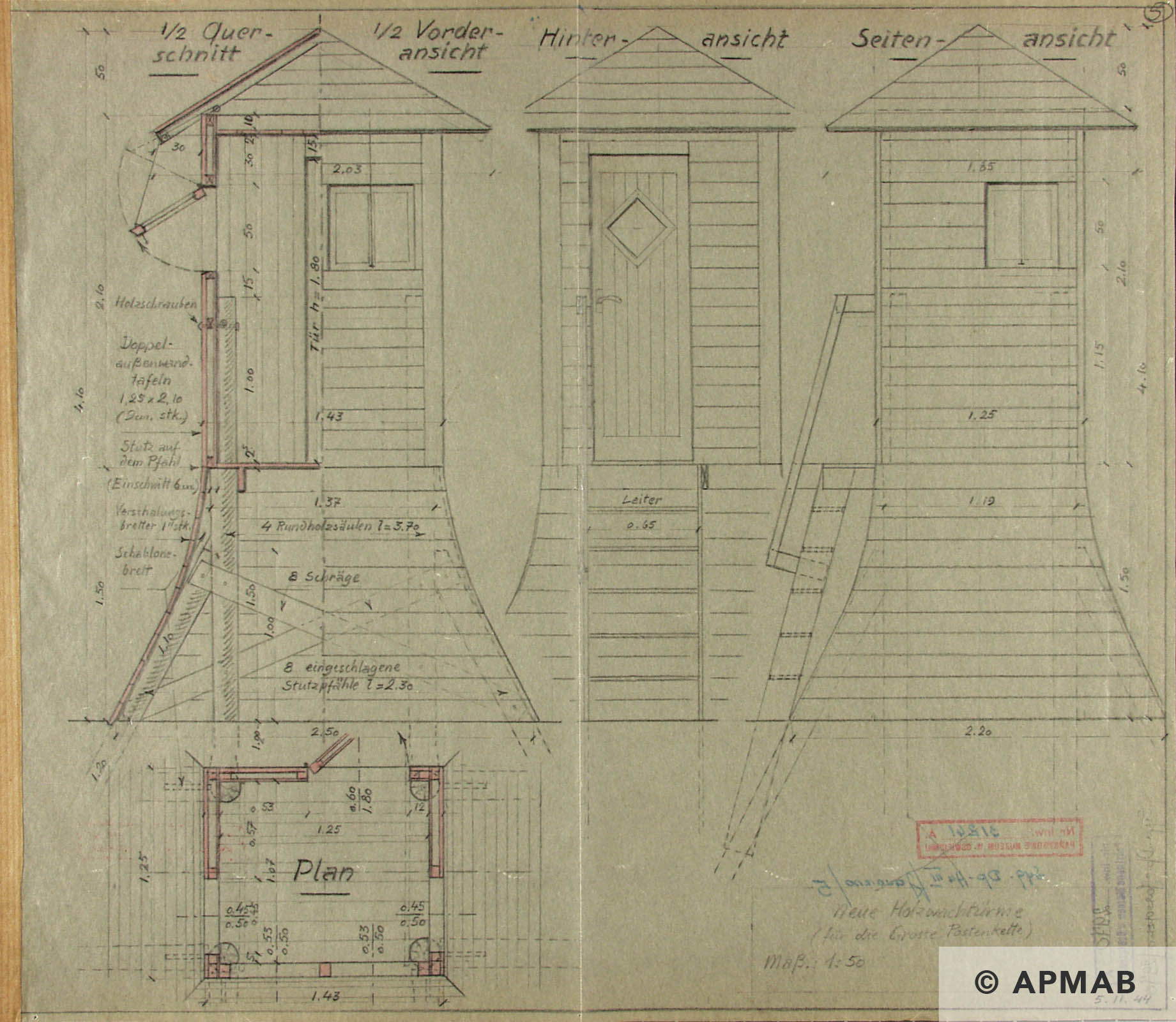

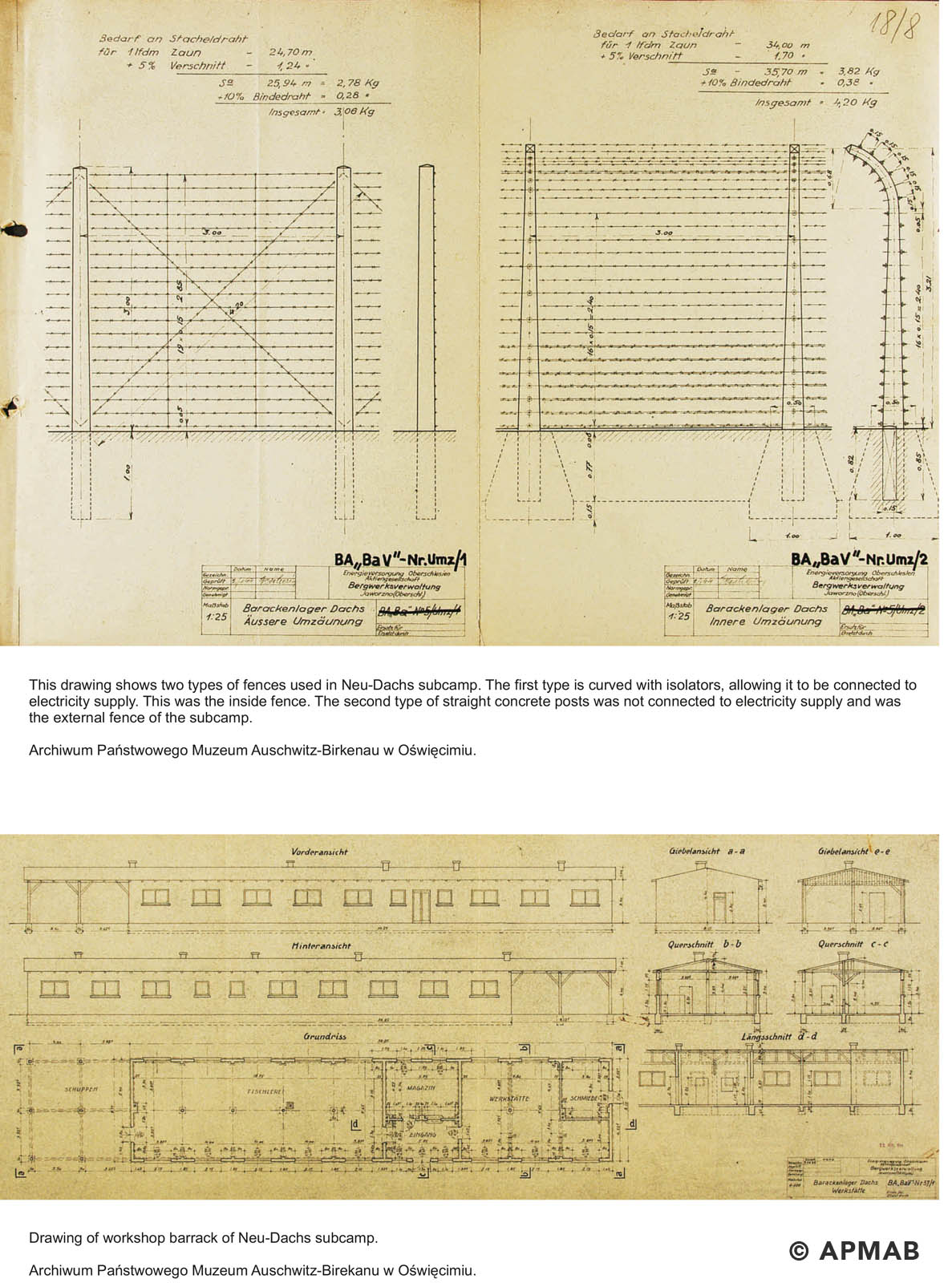

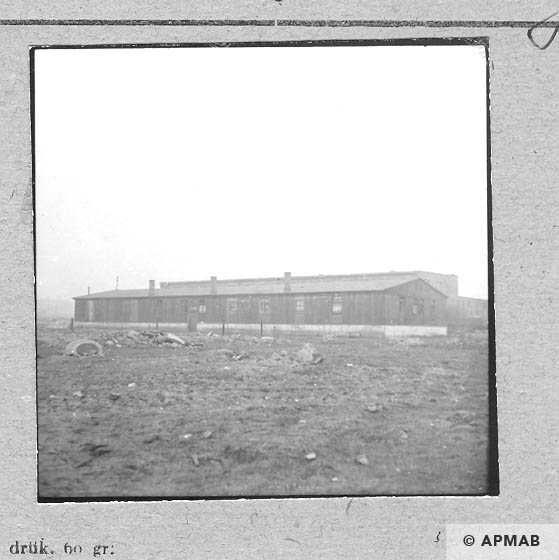

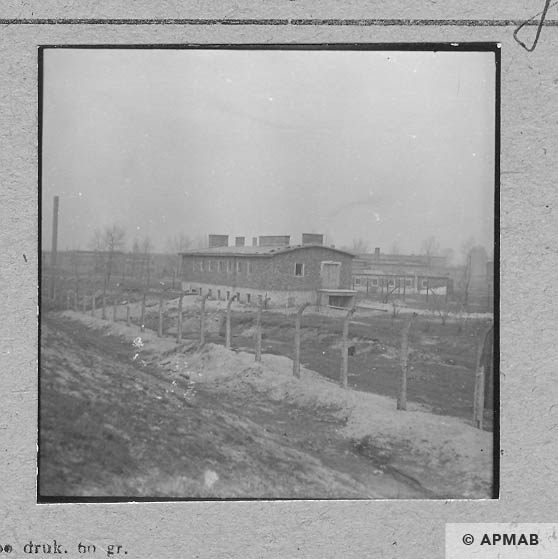

The sub camp Neu-Dachs was located near the mine Dachsgrube at the intersection of the highway Jaworzno to Katowice with the road running to Wysoki Brzeg. Upon arrival, the first transport of prisoners to the Auschwitz sub camp Neu-Dachs found just a wooden barrack used as a camp kitchen and barracks for the SS. The camp was surrounded by barbed wire strung on wooden posts, and at the four corners primitive wooden guard towers.[3]

It was planned that the sub camp in Jaworzno would eventually accommodate 5,000 prisoners and the newly arrived Auschwitz prisoners immediately set upon the camps expansion. Up until November 1943, 20 barracks and warehouses were built. When finished Neu-Dachs comprised 14 prisoner accommodation barracks, three latrines, camp hospital, kitchen, clothing store, boiler room, sauna, laundry, workshops and warehouses for the storage of the camp prisoners‘ clothes and food. The camp occupied an area of nearly 6 acres. The camp was surrounded by a double fence of barbed wire, hung on concrete posts. From the south and west, the camp was surrounded by forest, whereas in the north, the Krakow-Katowice road ran along the camp. In the northern part of the camp a high brick wall was built to prevent observation of the camp, by third parties. The primitive wooden guard towers were replaced with solid masonry structures, which were located on the corners of the camp and in the middle of each side of the fence. Lighting was installed on both the fence and on the guard towers lighting. The main entrance to the camp of Neu-Dachs was located on the south side. At the main gate there was the guard house and garage. About 100 meters south of the sub camp there were barracks for the SS men serving in the sub camp Neu-Dachs.[4]

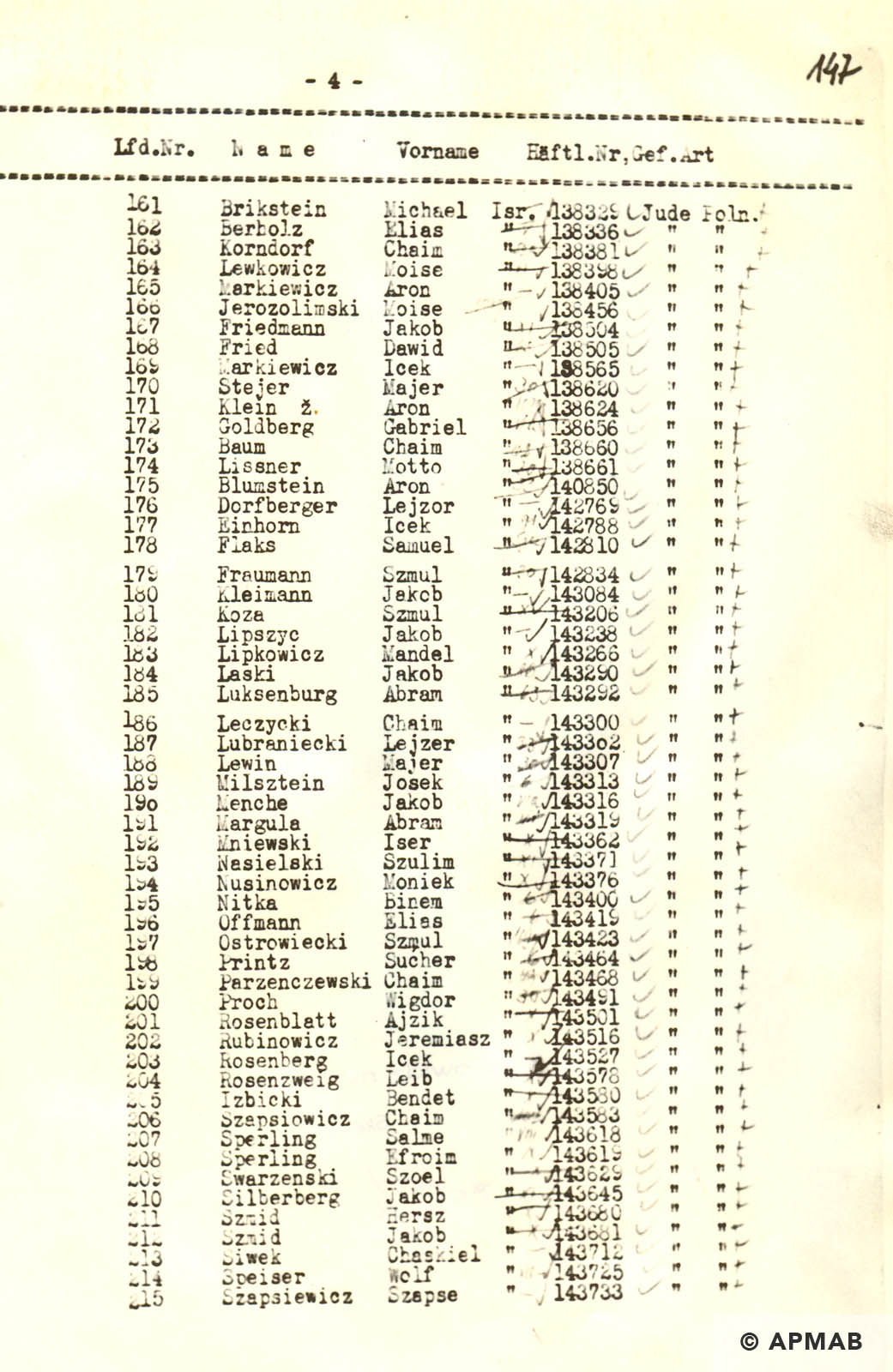

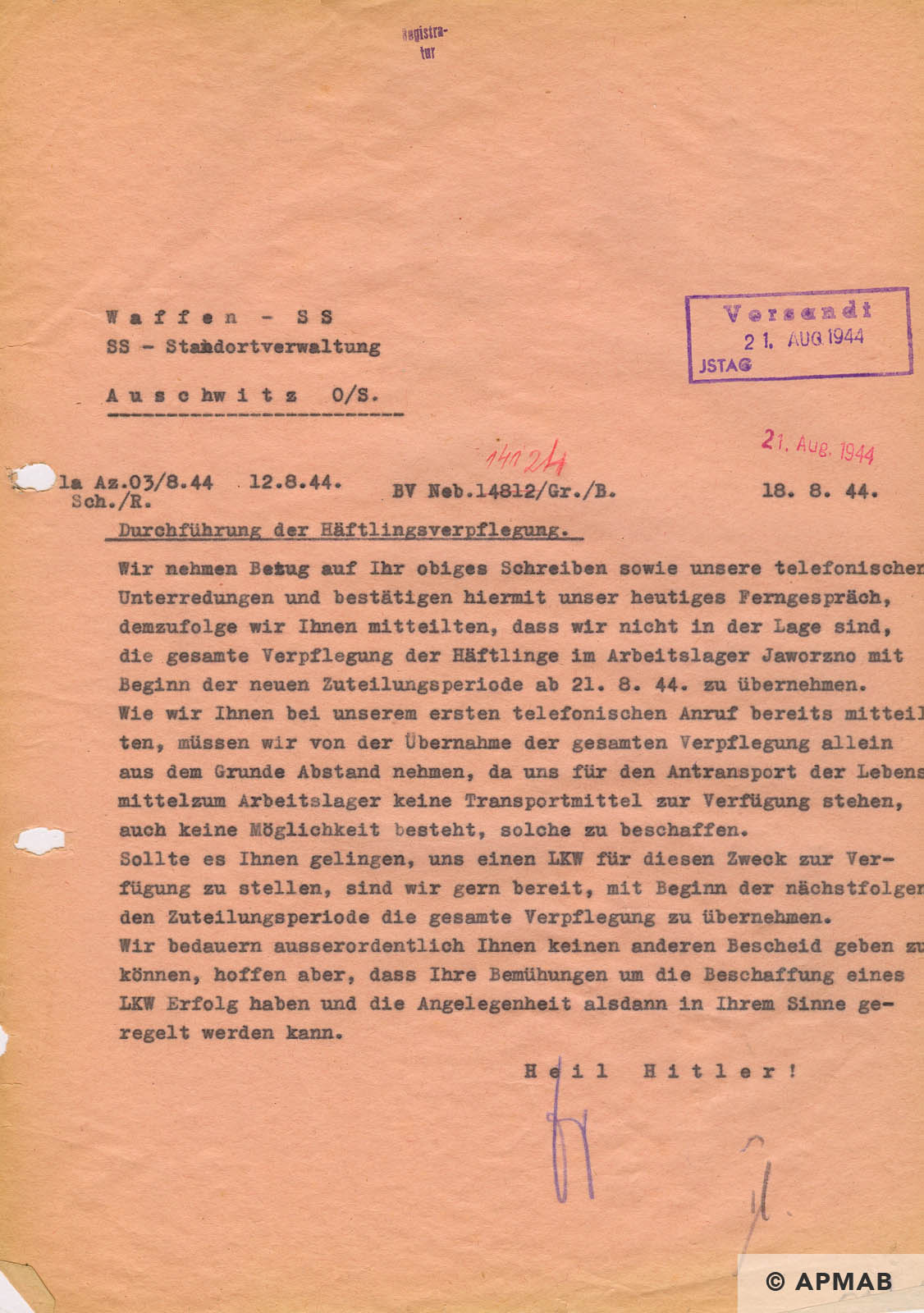

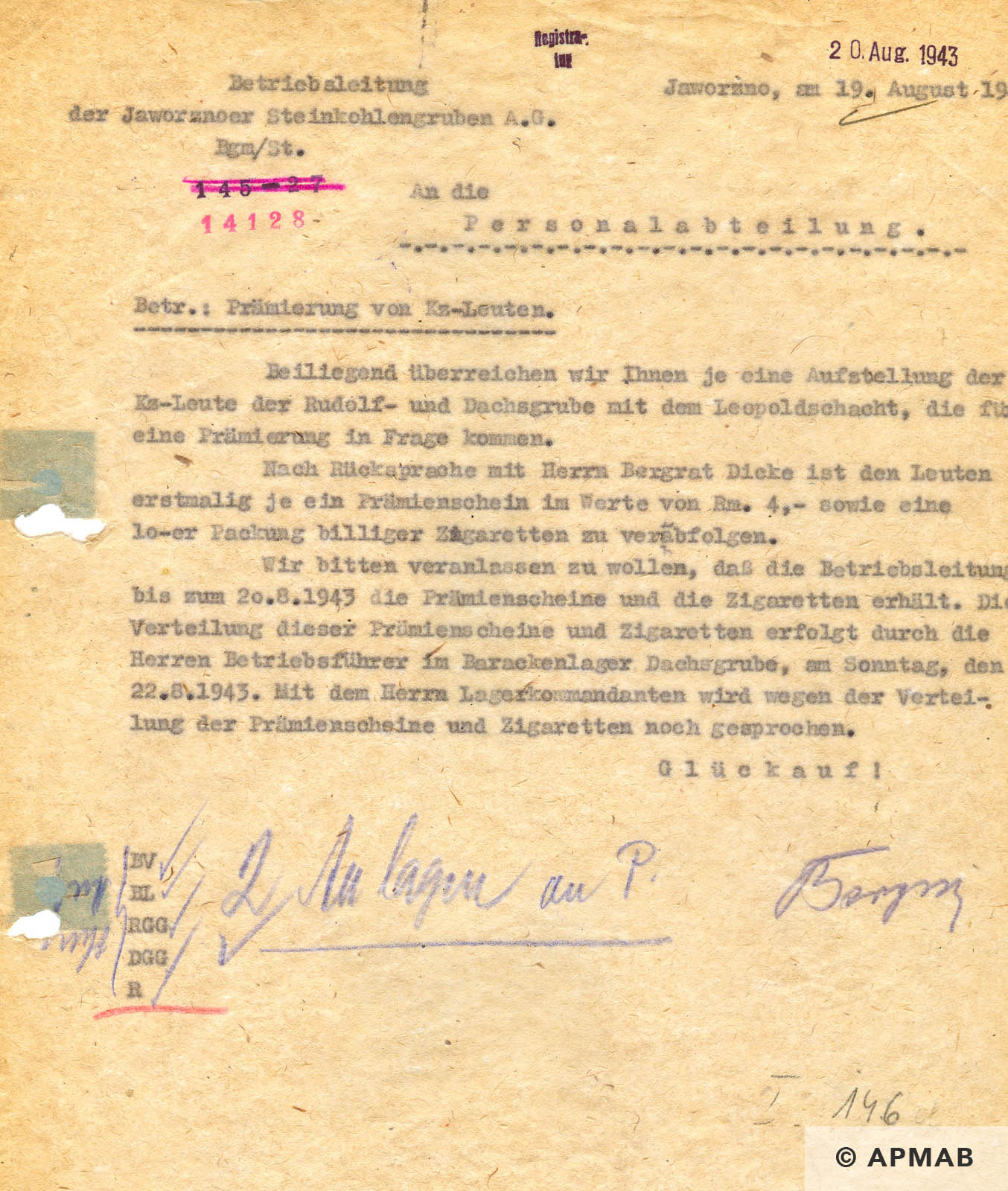

In August 1943, the number of prisoners in Neu-Dachs was around 1,600, in January 1944 – around 2,000, in the summer of 1944 – around 3,200, and shortly before the evacuation in January 1945 the figure was 3,664. The prisoners in Neu-Dachs were mostly Jews from across Europe – Greece, Poland, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, France and Germany. [5]

The prisoners were housed in 14 wooden huts, with windows, and slept one to a bunk on three tier bunks. Initially, all were dressed in standard prison stripe uniforms. Later, the prisoners were issued with civilian clothes from the victims of Auschwitz-Birkenau – the jackets had a square of standard prison stripes sewn on the back. To work in the mines some of the prisoners were issued special clothing, but this did not prevent them being injured or suffering from the cold. [6]

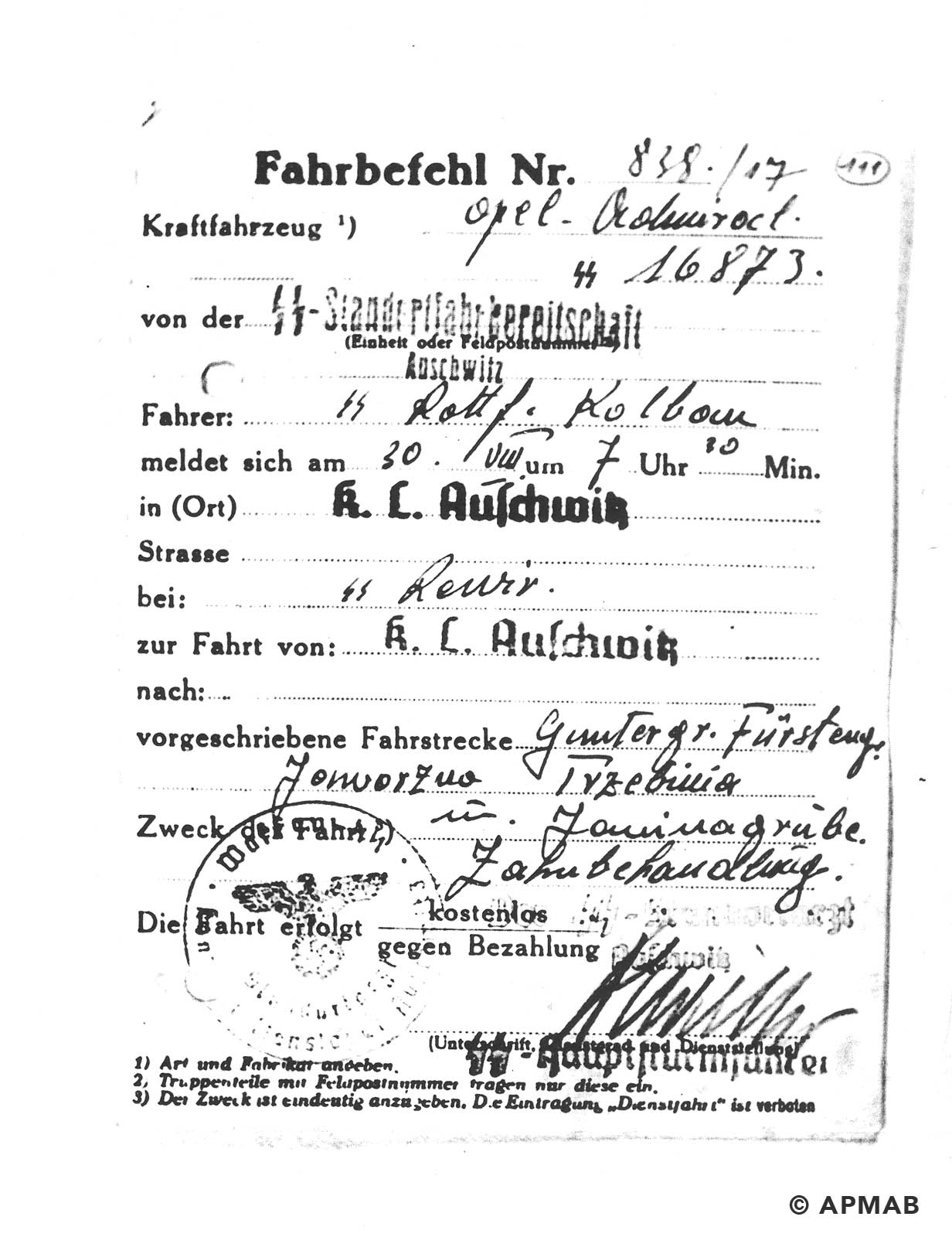

After the expansion of the camp, most of the prisoners were employed in the mines, Dachsgrube, Rudolfgrube and Richardgrube, expanding the Kraftwerk Friedrich-August and in building the Kraftwerk Wilhelm. The prisoners worked in three shifts.

Commonwealth prisoners of war from Working Party E596 worked alongside the Auschwitz prisoners in the coal mines of Jaworzno. Their living and working conditions were difficult but nevertheless they received significantly better treatment than the prisoners of the sub camp Neu-Dachs, “One mixed party of British Commonwealth prisoners, which included a number of New Zealanders, were sent to a coalmining camp (E596) in Jaworzno. They were billeted with a reasonable amount of space at an old boarding school and were regularly supplied with Red Cross food parcels. By 5 October they were below the surface pushing trucks of coal and in a month or so were working at the coal-face. The hours were long, the mine was worked for the whole twenty-four hours in three shifts, and there was only one Sunday in four free for the prisoners. Almost all were inexperienced in mining and there were numerous accidents: fingers crushed between trucks, arms broken by falls of coal. Fortunately for the men, reports on the mines were closely studied by the various authorities responsible for the welfare of our prisoners, and a careful check was kept on them by neutral inspectors. Conditions might otherwise have been much worse.”[7]

After the war, Antoni Kucharz, a former civilian employee at one of the mineshafts, testified, “ One cage had a capacity to transport 6 people. As a result of the orders of the mine management, for which it is difficult to find any technical justification, they (the Auschwitz prisoners) did not go down, like miners to level 165, where works were carried out, but lower to the new level 177. Only then did they return to level 166 (165) with three ladders, climbing a height of 12 m so one change (of shift) went down those stairs and the other went out. Driven from below and above by German guards, who wanted to reduce the time to leave, people were knocked off the ladders. All this took place in the dark, because the lamps were ordered to be turned off because of the danger of fire. There were shouts and cries from there. The prisoners worked essentially in the same positions as civilian workers,(….) in mining and stone works. Prisoners of better physical condition were employed here. They worked together with Polish miners. They had certain standards to comply with. If they did, they were given peace. It was worse…….when transporting carts, transporting wood and other materials. These prisoners worked mostly alone. Each contact with the supervisor ended with a beating. Work in a mine requires proper physical condition. Civilian workers were given special, additional food stamps (…). The prisoners, however, did not receive any extras apart from camp food. They generally looked bad. All the more that because they came to Jaworzno straight from the Auschwitz camp. They were emaciated and could not cope with this hard work and endured the effects of underground work very badly. Working conditions were very hard. (….) moisture and cold prevailed on the transport routes where most of the prisoners worked. Prisoners were soaked and cold due to constant soaking of their legs. When doing similar wet works, sinking shafts, transition works, civilian workers received protective clothing: waterproof clothing, rubber boots. The prisoners did not receive any protective clothing; they wore wooden clogs that didn’t protect their legs at all. Sometimes miners gave them their so-called skins. Diarrhoea was widespread among prisoners. We worked in three shifts. The day lasted 8 hours and 45 minutes. We worked almost every Sunday, except those during which major repairs were carried out in the shaft, (servicing) winding machines, etc. On Sundays, people working on stone works were moved to coal works. For our company (Rode), a larger group of prisoners worked at 300 m. Although their work was wet, they were doing better. We worked near a shaft where they could always be provided with some food from the canteen for civilian workers. Over time, this became the rule. Often, workers did not use their lunches so that some of the soup could be delivered to prisoners. In addition, it was customary throughout the mine that the workers gave their food supplement to the prisoners as soon as they went underground. Each of the workers had his own prisoner. Especially those prisoners who worked alone were exposed to constant harassment from the supervisors, who were almost exclusively of Germans.” [8]

In the testimonies of former prisoners and civilian employees there are many comments on the behaviour of the German employees supervising the prisoners. They used their privileged position and often cruelly tormented prisoners, beating them and abusing them, even leading to the deaths of prisoners: “One of the biggest sadists was Knopp. Many prisoners suffered from diarrhoea. If the prisoner relieved himself somewhere, Knopp grabbed the prisoner by the neck and wiped the faeces on his face. He ordered the prisoners to carry faeces in their hands, regardless of whether this or that prisoner did it, while beating and abusing the prisoner. Other sadist supervisors were: Biskup, Podkowa, not to mention Rempe, who was the chief in the Kościuszko shaft. Once, one of the prisoners did not come to the surface. There were strict rules for this eventuality. All exits from the mine were immediately closed. The SS came underground. It turned out that he was a Russian prisoner, short, stocky a Mongolian type, he felt sick, so he had lain down somewhere and fell asleep. When he noticed that it was already after the end of the shift he moved towards the shaft. Then he saw the SS men walking (towards him), started to run and hid between the trollies. When he was caught, he was beaten up and beaten all the way towards the shaft. There he was leaned against the wall and forced to dig. When he fell down, the Kapos were ordered to pick him up and continue digging, and when he could not get up, they started treading on him with steel (soled) shoes and jumping on him. The unconscious man was taken to the surface and dragged to the bathhouse. There, when he was revived, he was again trampled on and then taken by cart to the camp, where he died a few days later. I heard about another incident from the miners. Once two Germans came to the detachment, a foreman and a master in charge. One of the prisoners – a Jew, who allegedly failed to fulfil his duties, was beaten so badly that they threw his corpse into the coal trolley. The workers who received the coal, when they saw that a trolley was coming, pulled him out of the trolley and put him on a bench. However, the Germans, coming back (….), saw him and drowned him in the sewer.” [9]

Knopp was from Silesia and spoke perfect Polish. In addition to beating the prisoners from the Neu-Dachs sub camp, he also hit civilian employees. Exceptional brutality was also exhibited by the foreman Linn, who delighted in beating the prisoners climbing the ladders from level 177 to go to level 165 and the supervisor Rempe who according to witnesses, was responsible for the deaths of two prisoners.[10]

The SS guards also mistreated prisoners. They did not spare the exhausted prisoners when they left the mine for the surface: “When the prisoners left for the surface, this took about 0.5 hours. The SS organized various games for themselves. For example, a packet of cigarettes or matches was placed on the curb and the prisoners were ordered to take them. When the prisoner bent down for the cigarettes, a German shepherd dog would attack him. In the end, however, the prisoners found a way to stop the game. Namely, they wrapped one hand in rags, which were pushed into the dog’s mouth, and the other took the cigarettes. As a result, the SS stopped this game.”[11]

[1] Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Neu-Dachs [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 57-60.

[2] https://www.lamsdorf.com/working-parties.html. Viewed 28 September 2019.

[3] Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Neu-Dachs [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 62.

[4] Description of the sub-camp Neu-Dachs based on original plans and Franciszek Piper, Podobóz Neu-Dachs [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12.

[5] Piper, Franciszek Podobóz Neu-Dachs [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 71-73.

[6] Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Neu-Dachs [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 74.

[7] https://www.lamsdorf.com/working-parties.html. Viewed 28 September 2019.

[8] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of Antoni Kucharz, Vol. 51, p. 147 – 149.

[9] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of Jan Broniowski, Vol. 51, p. 153 – 154.

[10] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of Antoni Kucharz, Vol. 51, p. 149 – 150.

[11] APMAB. Zespół Oświadczenia, testimony of Antoni Kucharz, Vol. 51, p. 150.

Literature:

Piper, Franciszek Podobóz Neu-Dachs [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 57-111.

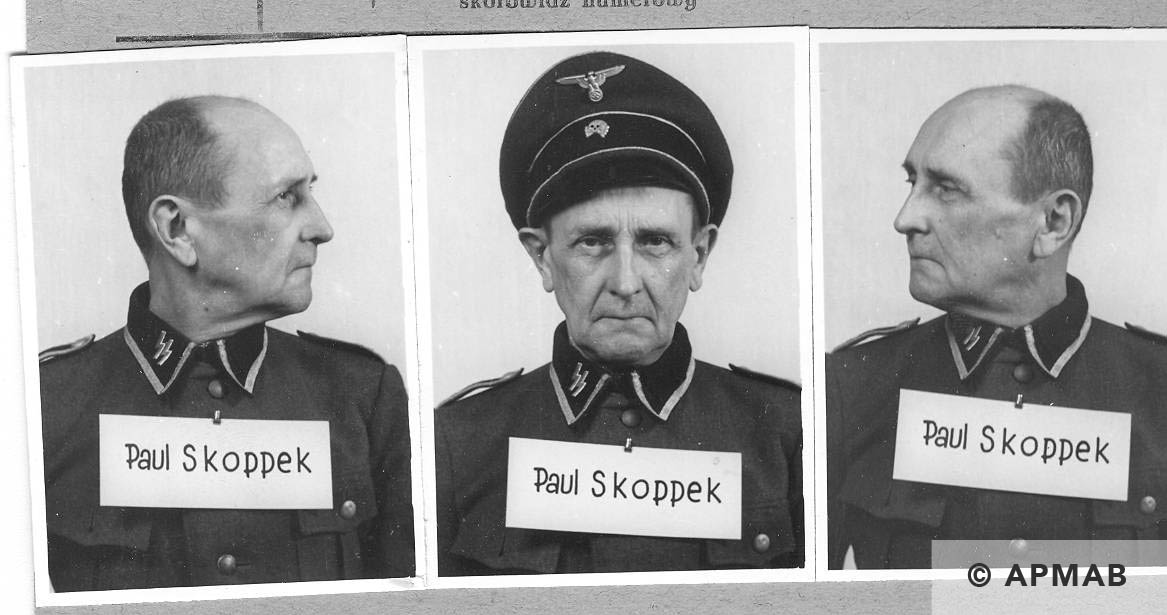

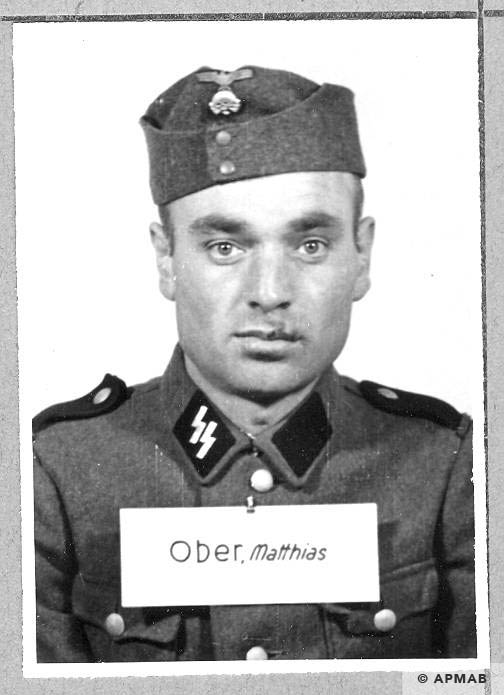

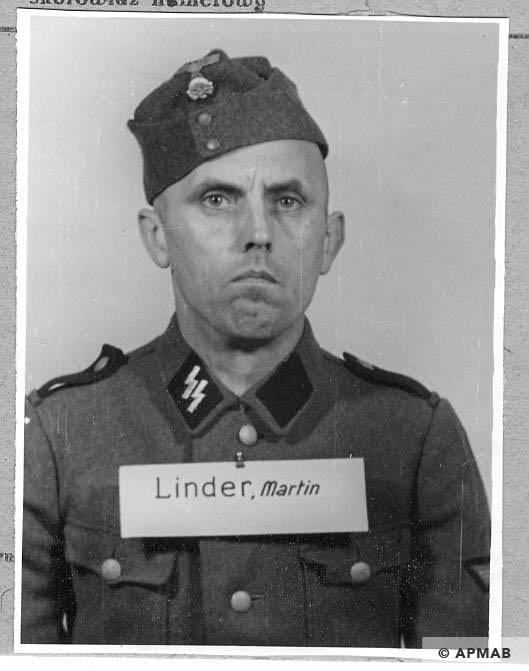

The SS Guard Unit

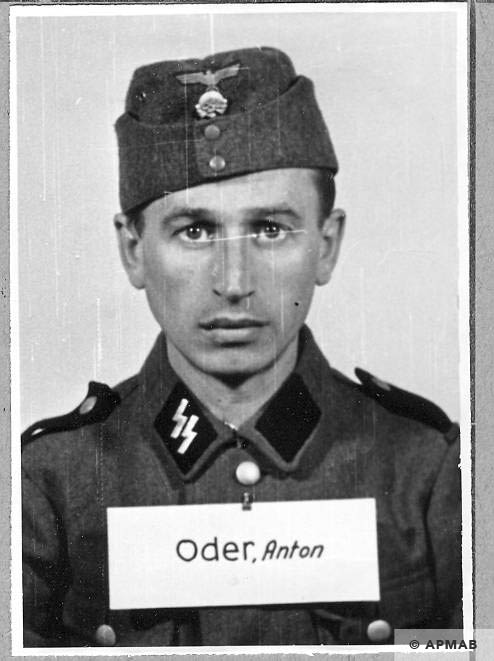

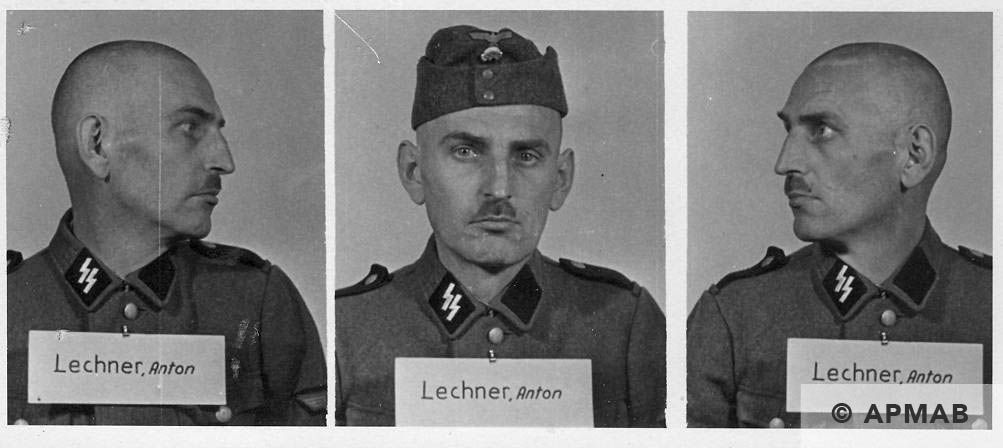

The Lagerführer of sub camp Neu-Dachs throughout its existence was SS-Obersturmführer Pfütze. His deputy was SS-Unterscharführer Weismann. The function of Rapportführer was performed by SS-Untersturmführer Olejak, Kommandoführers were SS-Rottenführer Marfiewicz and SS-Mann Lausmann, clothing store manager was SS-Rottenführer Anton Lechner and SS-Rottenführer Witowsky was the head of the political branch. The Sanitätsdienstgrad was initially led by SS-Oberscharführer Ontl from July 1943, then SS-Unterscharführer Kampfus from August 1943, SS-Unterscharführer Franke from December 1943, and finally Unterscharführer Hantl from October 1944 to January 1945. [1]

The SS guard unit consisted of between 200 and 300 men mainly from Germany, Slovakia, Romania, the Ukraine, and ethnic Germans from Poland so called Volksdeutsche. [2]

The first Lagerältester was Bruno Brodniewitz, prisoner number 1 and who between 1940 to 1942 was Lagerältester in the main Auschwitz camp and in 1943 in the Zigeunerlager in Birkenau. Brodniewitz was especially brutal towards Jewish prisoners. In 1944 he was transferred to the Eintrachthütte sub camp and was succeeded by Kurt Pennewitz. [3]

[1] Piper, Franciszek, Das Nebenlager “Neu-Dachs”, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz 1971 Nr 12, p. 65.

[2] Piper, Franciszek, Das Nebenlager “Neu-Dachs”, [in:] Hefte von Auschwitz 1971 Nr 12, p. 64.

[3] Rudorff, Andrea, Neu-Dachs (Jaworzno) in Des Ort des Terrors Band 5, Geschichte der Nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. C.H.Beck 2007, p 287.

Literature:

Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Neu-Dachs [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 57-111.

The SS Guards

References:

BA Ludwigsburg B162/2680 and B162/2679.

Zppw-auschwitz.pl Zwiazek Polaków Pomordowanych w Auschwitz. List of 8,500 SS men in KL Auschwitz.

IPN database of Auschwitz SS guards. https://truthaboutcamps.eu/th/form/60,Zaloga-SS-KL-Auschwitz.html.

Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Neu-Dachs [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 57-111.

The Evacuation of the Sub Camp Neu-Dachs

The evacuation of the sub camp Neu-Dachs began in November 1944, when some of the prisoners, Poles and Soviets were transported back to Auschwitz II-Birkenau, and onward to the Mauthausen and Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camps.

The final evacuation of the camp began after the Allied bombing raid of 15 to 16 January 1945 on Jaworzno which destroyed the camp kitchen and food storage barracks. As a result of the bombing dozens of prisoners of Neu-Dachs were killed. [1]

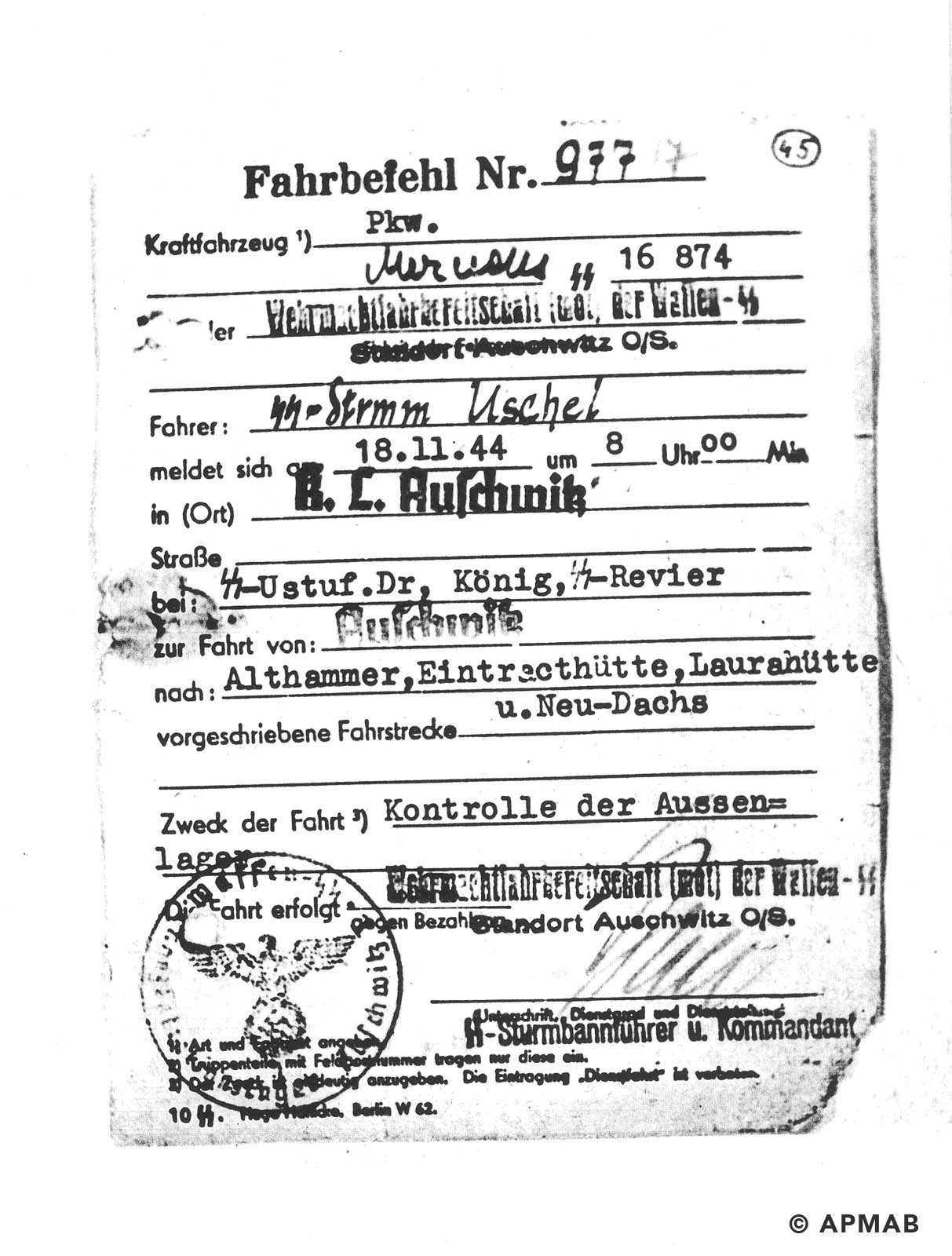

The next day, January 17 1945 all prisoners able to march, about 3,200 were formed into columns and under the escort of the SS guards marched in the direction of Chorzów. Before leaving the prisoners received a loaf of bread and they could take personal items – clothes and blankets. The prisoners were marched on foot through Chorzów, Bytom, Blachownia Śląska and Koźle to the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, where after a few days they were transported to the Buchenwald concentration camp. Approximately 400 prisoners too sick or unable to walk, were left in the camp, and were liberated by the Red Army on January 19, 1945. [2]

[1] Czech, Danuta, Kalendarz wydarzeń w KL Auschwitz, Oświęcim 1992, p. 836.

Literature:

Piper, Franciszek, Podobóz Neu-Dachs, [in:] Zeszyty Oświęcimskie [1970] Nr 12, p. 57-111.

The Post War History of the Former Sub Camp Neu-Dachs

After the liberation of Jaworzno, the communist authorities found the former Auschwitz sub camp virtually intact. In the newly founded Polish People’s Republic there was a need for prison facilities and the existing facilities of the former Neu-Dachs sub camp proved ideal for a Centralny Obóz Pracy (COP) (Central Labour Camp). This camp was probably established in February 1945 and work was immediately begun to adapt the infrastructure of the former Neu-Dachs sub camp.

At the time of the creation of the Jaworzno COP, there were 15 wooden barracks and numerous brick buildings such as: baths, kitchen, hospital, delousing room, workshops, warehouses, etc. The existing infrastructure was hugely expanded. In a report of the International Red Cross committee that visited the camp in 1947, there were already about 24 large barracks. The camp fence consisted of a double row of electrified barbed wire, with twelve stone guard towers between them, equipped with floodlights and machine guns. In addition, from the north, the camp was shielded by a wall 5 meters high, which prevented unauthorized observation from the Katowice-Krakow road. There were several buildings outside of the camp. [1] The design of the camp was remembered by Gerhard Gruschka: “(…) we saw (…) guard towers and a barbed wire fence behind which grey barracks stood in a tight row (…). on two sides, the camp was additionally fenced with a high wall just behind a double fence under high voltage. There was a brick building with a wide crematorium chimney near the walls.”[2] Inside the camp, separate zones were created using barbed wire fences, in which specific groups of prisoners were detained: Polish prisoners convicted of a crime, Reichsdeutsche and Volksdeutsche (women and men), prisoners of war (separately soldiers with non-commissioned officers and officers) and members of the Waffen SS.

Initially, interned in the COP Jaworzno were Germans, members of the anti-communist underground army, ordinary criminals, Volksdeutsche, people suspected of collaborating with the Nazi occupier and imprisoned on the basis of the sentence of the prosecutors were detained in the camp.

In February 1946, there were 7,875 prisoners in the camp. This number gradually increased: in June 1946 the number of prisoners had increased to 12,370, of which 5,559 were imprisoned outside the COP Jaworzno; in December 1946 17,395 (12,532 outside of the COP), and in March 1947 19,932 (15,557 outside of the COP) the largest number of prisoners registered by the authorities during the camp existence. There were also children in the camp – the largest number 406 in April and May 1948. At the end of the camp’s existence, the average number of prisoners was approximately 3,500 people.[3]

Living conditions at COP Jaworzno were extremely poor. This was due to the authorities not being prepared for such a large number of prisoners. Two or three prisoners slept to a bunk, and blankets and mattresses were missing. The food was similarly poor; due to serious shortages of food in Poland after the war, hunger at COP Jaworzno was experienced not only amongst the prisoners, but also the guards. Due to this, several camp guards deserted. In May 1945, the camp inspection report stated: “On the day of the inspection, they (the prisoners) received tea with herbs and 20 grams of bread for breakfast, and for dinner a soup, which according to the chef’s testimony contained meat, flour, groats, potatoes, beets, carrots, salt.”[4]

In 1945, as a result of an epidemic of typhus and typhoid fever, 972 prisoners died in the Jaworzno COP. In addition, other infectious diseases such as erysipelas, dysentery and venereal diseases were routine in the camp. Tuberculosis was also common amongst the prisoners. Due to deficiencies in the camp pharmacy, patients were treated mainly for their symptoms, but not their underlying illness – with painkillers, antipyretics and lime. Malnutrition weakened the immune system of the prisoners, and as a result led to starvation, which often resulted in death. In exceptional cases, the camp authorities allowed the patient to be transported to the Mining Hospital in Jaworzno.

Unfortunately, the exact number of victims of COP Jaworzno has not been exactly determined to date. According to the census prepared by the Central Board of the Prison Service in Jaworzno and it´s sub camps, 6,987 people died. According to Father Böss’s calculations, a total of 6,300-6,400 prisoners died at the COP. These figures, given the current state of knowledge, should be considered accurate.[5]

The dead prisoners from the camp were buried in two locations: at the outer wall of the Jaworzno COP (about 20-30 graves) and in the forest south-east of the COP. There are several hundred graves there. Most are anonymous. It wasn’t until 1948 that the dead were buried in light, wooden coffins, given a grave number and registered by the camp board.[6]

COP Jaworzno ceased to exist as a camp for internees and prisoners of war in August 1949, from which time it was transformed into a political prison. Political prisoners from the prisons in Strzelce, Grudziądz, Barczew, Kłodzko, Tarnów, Sanok, Śrem and Krakow were transferred to Jaworzno. In contrast, COP prisoners were transferred in October 1950 to the prison in Mysłowice, and the remaining 1,152 prisoners in January 1951 were sent to the camp in Chrusty.

However, this was not the end of the camp in Jaworzno. The abandoned facilities of the COP Jaworzno were selected in the spring of 1951 as the location of an experimental prison for juveniles. The project for the organization of prisons and correctional and educational work was developed in 1949-1950. Already during the development of this project in 1950 in Jaworzno, construction works were underway for a future juvenile prison with a capacity of 7,000 prisoners. Juvenile prisoners between 17 and 21 were to be incarcerated in the camp, although it was assumed that they could be kept in the facility until they were 25 years old.[7]

Initially, the juvenile prison in Jaworzno used the existing infrastructure from the Neu-Dachs sub camp and COP Jaworzno camp. In the years 1951–53, three new accommodation blocks, a community centre, a kitchen, a food warehouse, a boiler room, a laundry and a bakery were built by young prisoners. The prison area was fenced with a 5 m high wall.

At a distance of about 2 meters from the wall inside the prison there was still a relic from the period of existence of the Neu-Dachs sub-camp – the electrified barbed wire fence. The area was guarded by guards every 15 meters.[8]

In May 1951, juvenile prisoners were brought to Jaworzno from prisons all over Poland. From the railway station in Jaworzno they were escorted by guards armed with machine guns, and dogs to the prison. The residents of Jaworzno believing that they were young Nazis spat on them, cursed them and threw stones at them.[9]

Originally, juveniles convicted of political crimes were incarcerated in Jaworzno. The total number of juvenile prisoners sent to Jaworzno for political crimes was approximately 3,500. In time, however, juveniles convicted of criminal offences began to be sent to Jaworzno.

The political prison for juveniles, ceased to exist on December 31, 1955. After that time, only juveniles convicted of criminal offences were sent to Jaworzno, with sentences of up to five years and the physical abilities to work in mining. The prison was finally closed on August 31, 1956.[10]

[1] Miroszewski, Kazimierz, Centralny Obóz Pracy Jaworzno (1945-1950), [in:] Obóz dwóch totalitaryzmów. Jaworzno 1943-1956/Materiały z konferencji naukowej „Historia martyrologii i obozów odosobnienia w Jaworznie w latach 1939-1956”, Vol. I, Edit. Kazimierz Miroszewski and Zygmunt Woźniczka, Jaworzno 2007, p. 30.

[2] Gruschka, Gerhard, Zgoda – miejsce grozy. Obóz koncentracyjny w Świętochłoiwcach, Gliwice 1998, p. 60. The information provided by G. Gruschka regarding the crematorium is not entirely true. During the existence of the Neu-Dachs sub-camp as well as at Jaworzno, a crematorium was never installed.

[3] Miroszewski, Kazimierz, Centralny Obóz Pracy Jaworzno (1945-1950), [in:] Obóz dwóch totalitaryzmów. Jaworzno 1943-1956/Materiały z konferencji naukowej „Historia martyrologii i obozów odosobnienia w Jaworznie w latach 1939-1956”, Vol. I, Edit. Kazimierz Miroszewski and Zygmunt Woźniczka, Jaworzno 2007, p. 35.

[4] APKr, WUBPK, File. UBKr 45.

[5] Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950: wybór dokumentów, vol. 2, Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie [Edit:] Włodzimierz Borodziej and Hans Lemberg, Warszawa 2000, p. 179.

[6] Niemcy w Polsce 1945-1950: wybór dokumentów, vol. 2, Polska centralna. Województwo śląskie [Edit:] Włodzimierz Borodziej and Hans Lemberg, Warszawa 2000, p. 181.

[7] Szwagrzyk, Krzysztof, Okres młodocianych więźniów politycznych w Jaworznie 1951-1955, [in:] Obóz dwóch totalitaryzmów. Jaworzno 1943-1956/Materiały z konferencji naukowej „Historia martyrologii i obozów odosobnienia w Jaworznie w latach 1939-1956”, Vol. I, Edit. Kazimierz Miroszewski and Zygmunt Woźniczka, Jaworzno 2007, p. 44-45.

[8] Szwagrzyk, Krzysztof, Okres młodocianych więźniów politycznych w Jaworznie 1951-1955, [in:] Obóz dwóch totalitaryzmów. Jaworzno 1943-1956/Materiały z konferencji naukowej „Historia martyrologii i obozów odosobnienia w Jaworznie w latach 1939-1956”, Vol. I, Edit. Kazimierz Miroszewski and Zygmunt Woźniczka, Jaworzno 2007, p. 47.

[9] Szwagrzyk, Krzysztof, Okres młodocianych więźniów politycznych w Jaworznie 1951-1955, [in:] Obóz dwóch totalitaryzmów. Jaworzno 1943-1956/Materiały z konferencji naukowej „Historia martyrologii i obozów odosobnienia w Jaworznie w latach 1939-1956”, Vol. I, Edit. Kazimierz Miroszewski and Zygmunt Woźniczka, Jaworzno 2007, p. 47.

[10] Szwagrzyk, Krzysztof, Okres młodocianych więźniów politycznych w Jaworznie 1951-1955, [in:] Obóz dwóch totalitaryzmów. Jaworzno 1943-1956/Materiały z konferencji naukowej „Historia martyrologii i obozów odosobnienia w Jaworznie w latach 1939-1956”, Vol. I, Edit. Kazimierz Miroszewski and Zygmunt Woźniczka, Jaworzno 2007, p. 51

The Preservation Status of the Former Sub Camp Neu-Dachs

The remains of the Neu-Dachs sub camp can be found within the area of the streets ul Grunwaldzka, ul Puszkina and ul Inwalidów Wojennych in Jaworzno. The area is now occupied by a myriad of small businesses. It proved difficult to identify original buildings of the former sub camp Neu-Dachs due to changes made when the former sub camp was turned into the COP Jaworzno and 70 years of development of the area.

Most remnants are located in the southern part of the former sub camp, where the main camp gate was located. At ul Inwalidów Wojennych, there are two wooden barracks (slightly rebuilt and re-plastered) that stood on both sides of the main gate. They are the Blockführerstube and office.

In front of one of the barracks there is also a water basin used for fire-fighting. It has been filled in and a lawn planted on top. Behind the barracks you can see a line of posts with barbed wire stretched over them. On the same street, where it turns into the forest, an oval concrete fragment of a concrete watchtower from the time of the COP was also found. The watchtowers still existed in the 70s and 80s. The last of them was demolished in the 90s and the only remnant of the guard tower is the large oval concrete top.

There are also remains of the barrack which was described by the Auschwitz-State Museum as “Building of the “Wascherei”, where were the cells for prisoners.” (photo reference 6466).

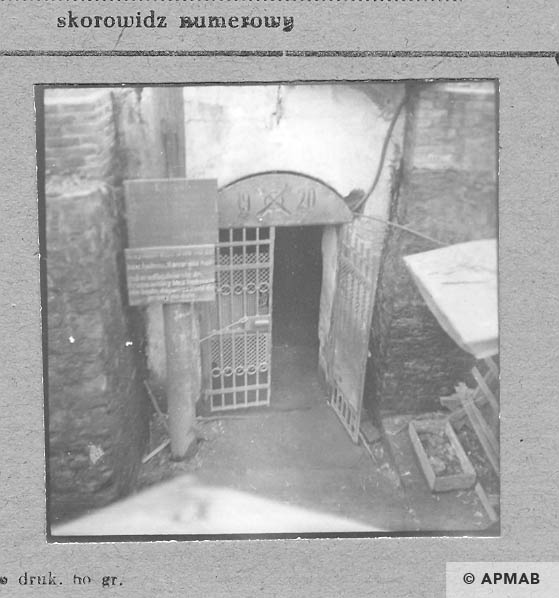

An original element of the Neu-Dachs sub camp is the side gate for prisoners located in the southeast corner of the sub-camp. Through this gate, prisoners were marched to work in the mine Dachsgrube.

The building described by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum as “SS Truppe barrack.” (Photo reference 6474) also remains.

While viewing the area, it is worth paying attention to the of remnants to the post-war use of this camp, when it was taken over by the MBP for use as the Jaworzno COP and then the juvenile prison. Elements of the camp buildings from this period can be found in the northern part of the Neu-Dachs sub camp. Earlier there were prisoners‘ barracks and warehouses. One prisoner barrack may still exist. In the 1950s, blocks for juvenile prisoners and a so called a community centre were built which still exist.

There are many other buildings in the area of the area of the former sub camp which may be from the time of the COP Jaworzno and Neu-Dachs sub camp.

In the area is the former building occupied by Commonwealth prisoners of war from work commando E596, a former boarding school.

Near the Jaworzno power plant are the remains of a former camp. It would appear the camp was from the war period but it is unknown whether prisoners or forced labourers were housed there.

Memorialisation

The Auschwitz sub camp and COP Jaworzno are commemorated with monuments and plaques. At ul Grunwaldzka there is a magnificent stone monument erected on a mass war grave for the prisoners of Auschwitz-Birkenau shot on January 17, 1945 by SS men during the evacuation.

The memorial to the victims of COP Jaworzno is, however, in the forest near the Podłęże Housing Estate. Here are the mass graves of the victims of the COP who were murdered or died between 1945-1952. It is an obelisk in the form of a tombstone with a cross cut out in a vertical plate symbolizing wings or sails, on which the Polish inscription reads: “PAMIĘCI POLAKÓW, UKRAIŃCÓW I NIEMCÓW, TYCH WSZYSTKICH, KTÓRZY CIERPIELI TU NIEWINNIE JAKO OFOARY TERRORU KOMUNISTYCZNEGO, WIĘZIONYCH, ZAMORDOWANYCH, ZMARŁYCH W LATACH 1945-1956 W CENTRALNYM OBOZIE PRACY MINISTERSTWA BEZPIECZEŃSTWA PUBLICZNEGO W JAWORZNIE. W HOŁDZIE POTOMNI.” (MEMORIES OF POLES, UKRAINIANS AND GERMANS, ALL OF THOSE WHO HAVE SUFFERED INNOCENTLY AS VICTIMS OF THE COMMUNIST TERROR, IMPRISONED, MURDERED, DIED BETWEEN 1945-1956. THE DESCENDENTS PAY TRIBUTE)

One of the few local Polish websites relating the history of an individual Auschwitz sub camp is that of the Jaworzno Museum. On the site visit of Tiergratnestrasse4Association to Jaworzno in September 2006 a representative of the Museum kindly showed us around the area of the former sub camp and COP and provided us with wartime photographs of the power plants in Jaworzno. The website of the Museum represents the history of the former sub camp Neu-Dachs through photographs, multimedia and written text. [1]

[1] http://www.obozdwochtotalitaryzmow.pl/o2t/neu-dachs.html

Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum Sub Camp Site Visit

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum visited the former sub camp on 11 March 1959 and took 14 photographs including:

- “House of the main commandant of Neu-Dachs; 1959.” (photo reference 6477),

- “Fragment of the wall surrounding the camp. Above the wall part of the SS-Truppe barrack.” (photo reference 6473),

- “Entrance to the coal mine “Komuna Paryska” where prisoners worked.” (photo reference 6470),

- “Building of Blockführerstube close to the main gate.” (photo reference 6472),

- “Building of the “Wascherei”, where were the cells for prisoners.” (photo reference 6466),

- “Mass grave of prisoners who died during the evacuation of Neu Dachs.” (photo reference 6469),

- “Main gate and fragment of fence in Neu-Dachs.” (photo reference 6476),

- “SS Truppe barrack.” (Photo reference 6474).

Other Photographs/Site Visits

The Jaworzno Museum has in it´s possession original wartime photographs of the Kraftwerk Wilhelm and Kraftwerk Friedrich-August. The Museum kindly provided us with copies which we present here.